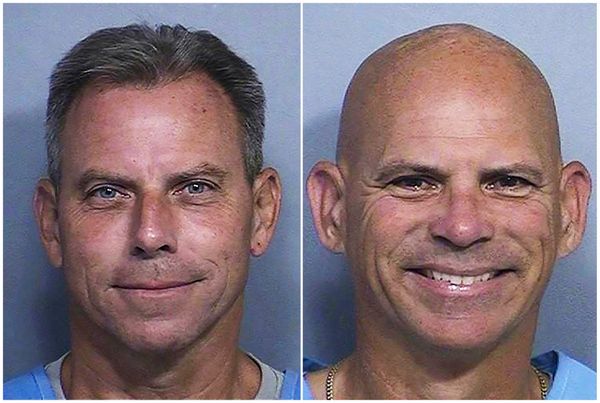

Los Angeles County District Attorney George Gascón has recommended that a judge resentence Lyle and Erik Menendez almost three decades after the brothers were sentenced to life without parole for murdering their parents.

The brothers were convicted in 1996 of first-degree murder for the 1989 killings of their parents, Jose and Kitty Menendez. If a judge approves the recommendation, it would make them eligible for immediate parole. Gascón said he believed the brothers have “paid their debt to society.” If a parole board agrees, they could soon be released from prison.

These extraordinary developments come in the wake of two true crime productions on Netflix: the scripted limited series, Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story, and the documentary, The Menendez Brothers. Both revivify the defence strategy used in the brothers’ 1994 and 1996 trials that they murdered their parents as a form of self-defence following years of alleged sexual abuse by their father.

In these two productions, we see the moral conundrum of so-called “true crime” on full display. That is, whose definition of “true” should viewers rely on when assessing the veracity of a narrative?

More often than not, there are two kinds of truth. There’s what really happened, and the narrative of what happened. This is a reality that I’ve noted as a criminologist and forensic historian and a police detective before that.

As a form of historical revisionism, true crime has shown both the willingness and ability to change official narratives, for better or worse.

True crime and the Menendez case

The true crime genre has taken off in recent decades, with countless podcasts, documentaries and TV series produced recounting gruesome and often unsolved murders. The genre has garnered criticism for focusing on, and sometimes, exploiting the real suffering of victims and their families.

The 2022 season of the Netflix Monster series, which told the story of Milwaukee serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, was widely derided as being exploitative and mired in controversy.

However, the second instalment, focusing on the Menendez brothers, has become an overnight cause celebre and a bandwagon clarion call to have the evidence in the case reviewed and the brothers’ life sentence reconsidered, if not jettisoned altogether.

The productions have renewed interest in this infamous case for those old enough to remember while, at the same time, introducing a new generation to the sordid details of the proceedings.

These details include, most notably, the controversial and ultimately failed defence strategy of depicting the murders as a form of self-defence following years of alleged sexual abuse the boys endured at the hands of their father, patriarchal record mogul Jose Menendez.

Following mistrials for both brothers in 1994, Lyle and Erik were convicted of the murders in 1996 and sentenced to life without the possibility of parole.

But now, in the wake of these same series and Gascón’s announcement, the case has been re-opened. “Significant new evidence” has been cited in the form of a potential additional victim of abuse by Jose Menendez. In addition, a letter from Erik to a cousin about the alleged sexual abuse of his father has been disclosed lending credence to the original defence position.

We might wonder if this evidence would have merited such attention, and the district attorney’s intervention, were it not for the cultural influence of the Netflix productions.

What we can say for certain is that this is not the first instance of true crime directly influencing the criminal justice system. HBO’s Paradise Lost trilogy of documentaries, along with the 2012 film West of Memphis, are generally credited with enabling the release of the wrongfully convicted West Memphis Three.

The first season of the Serial podcast in 2014 also led to the 2022 release of Adnan Syed after serving 20 years in prison for the 1999 murder of his girlfriend Hae Min Lee. That same conviction was reinstated in 2023 as part of an ongoing saga driven by intense public interest.

That interest is what differentiates the current iteration of true crime from its antecedents: it aims to transcend passive viewers and listeners to promote direct action, advocacy and public participation.

The four waves of true crime

While the term “true crime” may be comparatively new, as a cultural phenomenon it certainly is not. The Mystery Writers of America has issued awards for Best Fact Crime books since 1948. True crime in one form or another has arguably existed since the 1850s and was pioneered by Charles Dickens.

Yet it is still unclear what societal forces drive this trendy, cyclical interest in semi-true retellings or thinly fictionalized treatments of criminality. However, in my book, How to Solve a Cold Case…And Everything Else You Wanted to Know About Catching Killers, I argue that, true crime as we now know it can be delineated into four distinct eras, or waves:

The First Wave, circa 1850-1890, was purely literary. Key works included the likes of On Duty With Inspector Field by Charles Dickens and the Illustrated Police News.

The Second Wave, between 1965-1975, was also primarily literary. Its most notable works included Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and Helter Skelter by Vincent Bugliosi, who prosecuted serial killer Charles Manson.

In the third wave in the 1980s, true crime stories started to become multimedia, with Ann Rule’s book The Stranger Beside Me about serial killer Ted Bundy, and the semi-interactive NBC docuseries Unsolved Mysteries.

The fourth and current wave began in 2010. The hallmarks of this wave are unfolding before us in the Menendez case. The current wave is immersive, participatory and accessible. Amateur sleuths, advocates, pundits and activists proliferate with each new feature. Podcasts beget further podcasts.

Viewers and listeners are also keenly self-aware and facetiously self-deprecating. True crime is consistently discussed in the context of — and perhaps even designed to promote — what can only be characterized immoderate consumption. Some true crime fans are, for instance, self-described “junkies” and “addicts” who “binge” content. And yet, depending on the case, these same “junkies” are newly empowered and qualified to demand action.

The legal and ethical questions that arise are what cases make their way into this ecosystem and whose story are they to tell? How is a series on Dahmer a bridge too far when, two years later, another same series created by the same producers can alter the course of California legal history?

These are, of course, unanswerable questions. In the meantime, however, the Menendez brothers’ saga is a cautionary tale about how the invisible hand of the true crime market will select certain crimes over others — and prioritize certain victims and offenders alike over other — based on criteria we still don’t fully understand.

Michael Arntfield does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.