My family is spending this year in Madrid or, more precisely, three metro stops from Real Madrid’s Santiago Bernabéu stadium. A friend often takes me to matches. The ritual starts with the previa, literally “previous”, but roughly “prematch”, over a seafood feast accompanied by a bottle of cold Albariño in a restaurant near the Bernabéu. Usually I pay about €30 for the cheapest match ticket but, once inside the vast stadium, we try to sneak into better empty seats.

There’s something incongruous about Real Madrid: football’s biggest club plays in a second-tier capital in a struggling, mid-sized country. The team that meets Liverpool in Saturday’s Champions League final has about 280 million followers on social media, estimates KPMG, more than any other sports club bar their rivals Barcelona, and more than all NFL teams in American gridiron football combined.

Real Madrid fandom is known as madridismo, as if it were an ideology. Yet the fan base mostly gets ignored, whereas there are popular narratives about Liverpool or Barcelona supporters. Stories about Madrid focus on star players and triumphs. So what does supporting Madrid mean? What is madridismo?

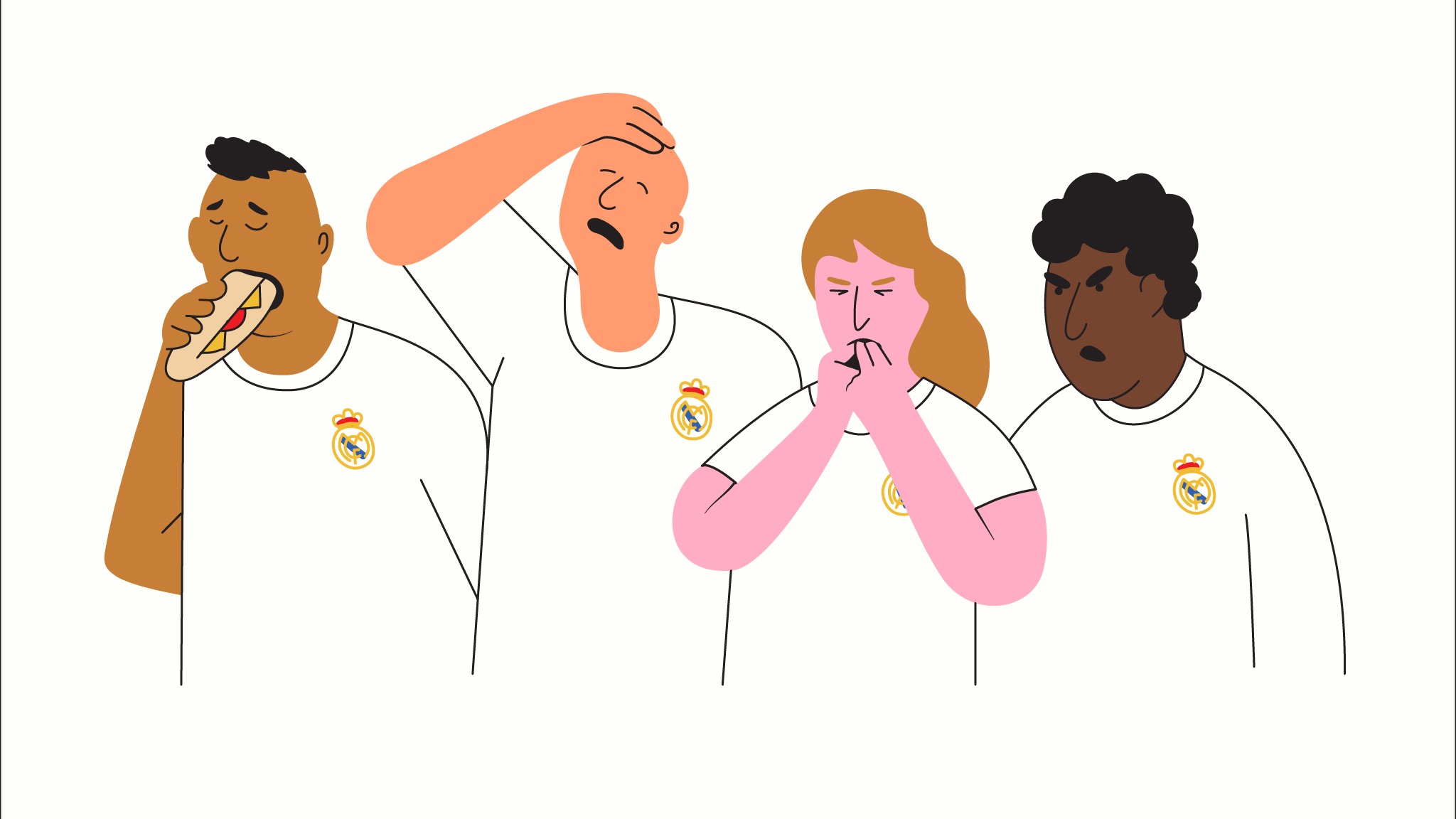

Madrid’s impossibly demanding fans are offended by anything short of excellence. They want players to sweat

It isn’t particularly madrileño — that is, the club has never aimed to represent the city. When the 125,000-place stadium got its name in 1955, it was much too big for Spain’s sleepy, impoverished capital. The Bernabéu stood just north of town, on the Avenida del Generalísimo, named after Spain’s dictator Franco, and near the highway to France, so even then the club looked towards Europe. From 1956 through 1960, the white-shirted Merengues won the first five European Cups.

For Spaniards at home and poor émigrés abroad, the club represented something rare at the time: a world-class Spanish institution.

Madrid’s impossibly demanding fans are offended by anything short of excellence. “They only stop whistling when their mouths are full,” complained Ferenc Puskás, the Hungarian star of the 1950s. They want players to sweat. The legendary Alfredo di Stéfano called the Bernabéu , the factory. Stars get castigated if they start acting bigger than the club (see Cristiano Ronaldo and Sergio Ramos) and are unsentimentally expelled the moment they decline. Fans will berate even hardworking local lads like Nacho or Dani Carvajal.

The crowd in the stadium is more middle-class than the broader Spanish fan base, and the Bernabéu’s characteristic sound isn’t cheering but a runrún, or murmur, as spectators dissect a player’s mistake in accents ranging from Murcian to Mexican.

Over the decades, the city has remade itself around the Bernabéu. As Madrid grew northwards, the stadium found itself in what is effectively the central business district. That drift north continues. The city’s “five towers”, or skyscrapers, arose this century on what was the club’s old training centre.

But the Bernabéu remains too big for the city, even the country. The freshly renovated stadium is a place to receive the world’s best, not Spanish clubs like Cádiz or Villarreal. Other Spanish fans care more about Real Madrid than vice versa: just as strong as madridismo is, hatred of the club of the capital which is supposedly (and sometimes actually) favoured by referees and governments.

Madrid fans shrug. Even the “Clásico” against Barcelona, the world’s biggest club game, means less to them than to Barça fans, especially since Barcelona’s recent decline. Success in Europe is Madrid’s chief objective, an obsession surely fed in part by Spain’s enduringly shaky national self-esteem. Unlike England fans, most madridistas backed last year’s foiled European Super League, the brainchild of their club’s president, Florentino Pérez.

The Bernabéu comes to life for Champions League knockout games. That’s when you see Madrid’s characteristic game at its purest: little collective fluency, a willingness to “suffer” for long stretches against more organised teams, and an unmatched “football of moments”, when Madrid briefly switch on full power, illuminated by the genius of Luka Modric and Karim Benzema. (Great footballers are born to play in the Bernabéu.) As the pre-game club anthem proclaims: “I am struggle! I am beauty!”

Just after Madrid’s last-minute goal against Manchester City, with the club needing to score again to survive, six minutes of extra time were announced. I’ll always remember the crowd’s roar: in that moment, it knew Madrid would win. The team had managed similarly improbable comebacks, or remontadas, in previous rounds against Paris St-Germain and Chelsea. As Jorge Valdano, former player, coach and technical director of Real Madrid, says: “In the Bernabéu, nothing is more real than magic.”

It will all count for nothing if they lose to Liverpool, but then Madrid seldom lose finals. Victory would give them their 14th European title, twice the tally of any other club.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2022