The private health insurance rebate costs Australian taxpayers nearly A$7 billion per year, and has cost over $100 billion since its introduction.

Yet the rebate’s return on investment has never been estimated.

In the middle of an election campaign and with a record budget deficit, it’s worth reflecting on why the rebate was introduced and whether it represents value for money.

Read more: INFOGRAPHIC: A snapshot of private health insurance in Australia

What is the private health insurance rebate, who gets it, and why was it brought in?

The private health insurance rebate is money paid by the Australian government to people who buy private patient hospital cover.

Eligibility depends on policy type (single or family) and annual income. Singles or families within incomes classified as Tier 3 do not receive any rebate.

The rebate rate is based on age and income. It is calculated as a percentage of the premium paid, so the more spent, the more money the government will provide, either through lower premiums or through your tax return.

The Australian government introduced a means-tested rebate to singles and families in 1997 to encourage people to buy private health insurance.

It thought an increase in private hospital cover would take pressure off public hospitals.

Read more: The debate we're yet to have about private health insurance

Cover had significantly declined due to premium increases of 75% between 1989 and 1996.

Around the same time, the government introduced the Medicare Levy Surcharge. This penalises higher income people for not owning private hospital cover.

It also introduced lifetime health cover loading, which makes people aged over 30 pay higher premiums if they decide to purchase private hospital cover for the first time, or drop their cover for three years or more (with exemptions for people going overseas).

Means testing on the rebate was removed in 1999, and a flat 30% rebate was applied to all policies. This formed part of the government’s support for cost of living pressures given the goods and services tax was being introduced.

At the time, there were several supporters of the rebate, such as the peak bodies for the private health insurance sector and private hospitals.

There were also strong opponents.

The Industry Commission (now the Productivity Commission) concluded the rebate would not help the public hospital system. A Senate Standing Committee concluded the rebate runs “counter to the Medicare principles of universality, equity and access”.

Changes to rebate policy settings over time

The then Coalition government increased the rebate in 2005 from 30% to 35% for people aged 65-69 years and 40% for people aged 70 years and over. This was to “reward older Australians for contributing to private health insurance costs for most of their adult lives”. It had little effect on membership and has been interpreted by some researchers and academics as a wealth transfer to older Australians.

The then Labor government reduced the rebate and increased the Medicare levy surcharge for high income earners in 2012, to limit government expenditure growth, after concerns the rebate provided “windfall gains” to high income earners. This policy increased private hospital cover.

The government has gradually reduced the rebate since 2014.

Does the rebate achieve its intended purpose?

The federal government now spends the same on the rebate each year as the South Australian government spends on its whole health system.

The purpose of the rebate was to increase private health insurance membership to reduce public hospital pressure. On these measures, it seems to have failed.

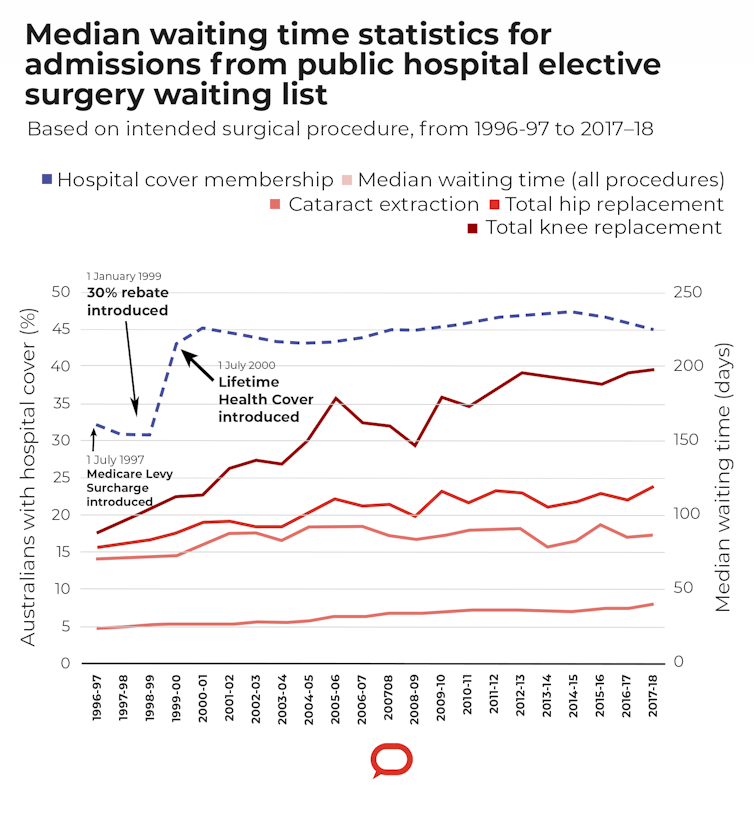

While private hospital cover increased dramatically from 31% to 45% just after the 30% rebate was introduced, most studies attribute the increase to the lifetime health cover policy.

There is also no strong evidence increasing private hospital cover takes pressure off the public hospital system, with data suggesting little, if any, impact. Public hospital elective surgery waiting times for three popular surgeries increased despite the dramatic increase in private hospital cover at the start of the millennium.

Some studies suggest increased private hospital cover could increase public hospital waiting lists. Shifting patients into private hospitals decreases demand for public hospital elective surgery, but the supply of surgeons also shifts to private hospitals, which means fewer resources for public hospitals.

Many people have also downgraded their cover because of systemic premium increases. This means members may still use the public system to avoid large out-of-pocket costs.

So what should the major parties do this election?

Both major parties should commit to reviewing the rebate’s return on investment and ditch the rebate if taxpayers are not getting value for money.

Removing the rebate would be politically challenging.

Some members would experience a premium increase of between 8 and 33%, adding to their cost of living. Older Australians with low incomes would experience the greatest premium increases.

Read more: Private health insurance 'carrot and stick' reforms have failed – here's why

That doesn’t mean there would be a collapse in membership but there would be some decline, potentially below 40% of the population.

Removing the rebate should be popular among Australians without private health insurance, which is more than half. They don’t receive any benefit from the rebate yet their tax is used to cover its cost.

A drop in membership means some people would get their elective surgery in public hospitals instead. But the money saved from the rebate would be more than enough to cover those extra costs in the public system, with funds left over.

Savings could be reinvested into the public system, where every Australian can benefit.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.