Cooking how-to videos, recipe blogs and mass-produced cookbooks may be relatively recent inventions, but our ancestors liked to cook, too. Archaeologists have found remnants of food resembling our own all over the world, from traces of burnt porridge on Stone Age pots to "beer loves" of bread in ancient Egypt. Yet, for much of history, cooking was an art passed down orally and not often documented in writing.

So what's the oldest known recipe?

The answer hails back to one of the oldest civilizations, although their recipes look a little different from the ones we see today.

While it may seem obvious with modern-day recipes, figuring out if an ancient document is a recipe actually poses big challenges for archaeologists. According to Farrell Monaco, an honorary visiting fellow and doctoral candidate at the University of Leicester who specializes in ancient Roman breads, "recipes" as we know them are a modern invention.

Ancient instructions for making food often didn't have weights and measures the way today's cookbooks do; precisely measured recipes became common only within the past few hundred years, Monaco said. Ancient medical concoctions also often contained edible components, making it challenging to decipher if a list of ingredients was meant for culinary or medicinal purposes. Add in the problem that some words from ancient recipes are untranslatable and others refer to ingredients that no longer exist, and identifying whether an ancient text contains instructions for making food can be a surprisingly difficult task.

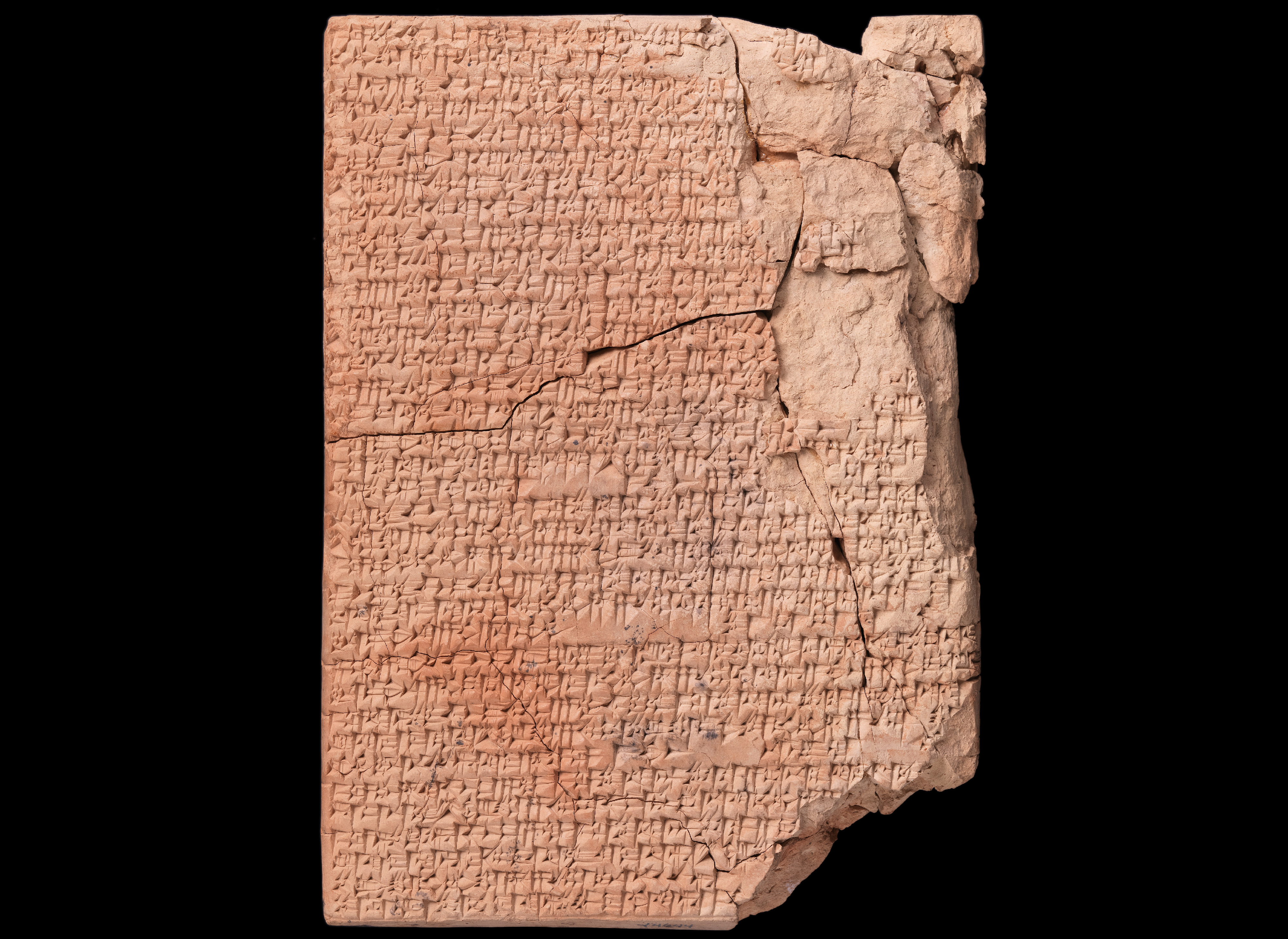

In fact, what we now know as the "oldest recipes" weren't identified as such for a long time. When four Babylonian clay tablets arrived at Yale University in the early 1900s, archaeologists struggled to translate the cuneiform script they contained. The tablets, each about the size of an iPad mini, hailed back to about 1730 B.C., and were written in what is now southern Iraq.

In 1945, scholar Mary Hussey suggested that the tablets were recipes, but colleagues in the field scoffed at her, believing they must be medicinal mixtures or alchemical concoctions.

"Food making is one of these sort of silent technologies," Gojko Barjamovic, a senior lecturer and senior research scholar in Assyriology at Yale, told Live Science. He explained that for much of history, recipes were passed down generationally, most often through women, so archaeologists didn't believe written recipes from the Mesopotamian era even existed.

Related: When did humans start cooking food?

Ancient broth, pie and stew

In the 1980s, archaeologist Jean Bottéro confirmed the Babylonian tablets were actually recipes. Still, he declared the food described on the tablets as inedible. It wasn't until recently that any of the recipes were revisited.

Barjamovic worked with an interdisciplinary team at Harvard to translate and recreate the recipes. This was a challenge, because many of the tablets were damaged, making them difficult to read. Even though some important ingredients on the tablets were untranslatable, Barjamovic's team was able to fill in the blanks to reconstruct the ancient foods.

They found that the tablets contained instructions for broths, a pie stuffed with songbird, green wheat, 25 types of vegetarian and meat-based stews, and some sort of small, cooked mammal. In many ways, the recipes resembled modern-day food from Iraq, with ingredients such as lamb and cilantro. But they also included some ingredients that might offend some palates, such as blood and cooked rodents.

Although one tablet contained more detailed instructions with measurements, many of the Babylonian recipes bore little resemblance to the detailed ones we're accustomed to today. One read, "Meat is used. You prepare water. You add fine-grained salt, dried barley cakes, onion, Persian shallot, and milk. You crush and add leek and garlic."

These tablets are the oldest known recipes, and there are also no known recipes that come after them for a long time.

"They kind of represent this funny little island of knowledge about culinary traditions from one specific place at one specific time," Barjamovic said.

Studying ancient recipes like these helps us value our own food more, Monaco said, and it shines a light on the cultural relevance of food throughout human history.

"It draws a beautiful throughline from us to them," she said.