What is it about reaching their 70s that makes great songwriters want to sing old songs they didn’t write? Paul McCartney reached backwards to pre-Beatles music and released an album of mostly Tin Pan Alley ditties, slipping in a couple of originals in the same style, in 2012, the year he turned 70. Bob Dylan took up crooning vintage standards associated with Frank Sinatra for the first of several albums in this vein when he was 73, in 2015. Now Bruce Springsteen, at 73, has offered up a new album consisting wholly of covers of soul-music songs from his younger days.

The music in all three of these cases is infused with the artists’ pleasure in doing something they had never gotten around to—or perhaps had felt they couldn’t or shouldn’t do—when they were younger. Exercising the privilege of age, with nothing left to prove or lose, they are singing what they feel like and have ended up expressing dimensions of themselves that hadn’t come through so potently in music of their own authorship. All three reveal qualities of gentleness and unpretentiousness; a kindness toward the creative world of their elders, now that they have become elders too; and a pride in showing what they can still do in a life stage of diminishing physical resources. With Springsteen alone, though, there seems to be something else in the music: He seems to be reminding us that he’s younger and asserting that he’s cooler than the rest. He decided to do covers, but his covers aren’t songs of his grandparents’ time or easy-listening radio; he’s doing mostly Black music from the postwar era of Motown and Philly soul. He’s not just crossing generational lines; he’s crossing lines of color. That’s how cool he is, even as a septuagenarian white guy.

The album, Only the Strong Survive, presents Springsteen as the lead singer on a selection of 15 songs, most of them from the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s. The curation is a nicely balanced, not-too-showy work of connoisseurship. It includes six numbers from the Motown labels as well as two titles from the writer-producers Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff of Philadelphia International, the soul-music power center likely within AM-radio range of Springsteen’s boyhood hometown in New Jersey. It also features former Top 40 hits such as Tyrone Davis’s “Turn Back the Hands of Time” and the Four Tops’ “When She Was My Girl” as well as rarities such as William Bell’s “I Forgot to Be Your Lover.” Virtually every tune was first or most notably released by an artist of color and was thought of in its day as soul music, the rhythmically lyrical school of secular pop guided by the spirit of Black gospel. The curious exception in this song list is “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore,” written for Frankie Valli by the Four Seasons house writers Bob Gaudio and Bob Crewe, and made a hit by the Walker Brothers, an act of theatrical white rock singers. At one point in his solo career, Springsteen’s late saxophonist Clarence Clemons included the tune on one of his albums, and now it’s here.

With the title song, Springsteen sets up his soul album as a statement of his sensibility. A hit for Jerry Butler in 1969, co-written by Butler, Gamble, and Huff, “Only the Strong Survive” is a muscular rallying cry, a call to triumph through masculine endurance and perseverance: “You gotta be a man, you gotta take a stand!” Springsteen has always been a hard-rockin’ rock-and-roller; he has never been known as a “blue-eyed soul” singer in the mode of white performers—from Van Morrison and Phoebe Snow through Hall & Oates and Michael McDonald to Joss Stone and many more—who built careers on adopting a music born of the Black experience. Springsteen’s earliest albums, made while he was still gigging on the Jersey shore, were hybrid creations laced with soulful numbers like “The E Street Shuffle” and tales of prophets “dressed in snakeskin suits packed with Detroit muscle,” young Black men who came to “light the soul flame.” As he explained much later in a concert, introducing a medley of Motown hits, “If you grew up along the Jersey shore in the ’60s or ’70s, you had to play soul music to survive.” He was already equating soul with survival and strength of will, rather than race, and casting it in roundly Springsteenian terms. At that point, though, when Springsteen was world famous for his rock records, playing a Motown set was so unusual for him that he felt the need to explain it.

For some reason—expedience or budget, most likely—Springsteen opted not to use the full E Street Band for Only the Strong Survive. The album’s co-producer, Ron Aniello, serves as the core band on every track, playing guitar, bass, piano, organ, electronic keyboards, drums, and percussion. Springsteen himself contributes guitar or keyboard parts on only a handful of tracks; specialty musicians (including some E Street side players) were brought in for the horns and strings. The arrangements by Aniello pay tribute to the original recordings with dutiful precision, and the overdubbed one-man-band scheme of the project gives the whole thing a hermetic, tightly programmed feeling that suggests none of the fluidity, the free emotionality, the spontaneity, and the kinetic energy of soul music.

As the singer, Springsteen sounds remarkably good for a performer who has been cannoning “Born in the U.S.A.” out of his throat for years. He sings the gentler songs such as “Nightshift” and “Soul Days” with impressive restraint, withholding the Okie dialect inflections that he has been using on ballads since he started to channel Woody Guthrie, with the Nebraska album. On the more propulsive numbers, such as “Turn Back the Hands of Time” and “When She Was My Girl,” he is strikingly disciplined, more David Ruffin than James Brown, tamping down the macho bravura that has virtually defined his stadium tours. Restraint and discipline are double-edged values, though: Springsteen is holding back the traits that have characterized his style for decades—or holding back the public self he has constructed with care.

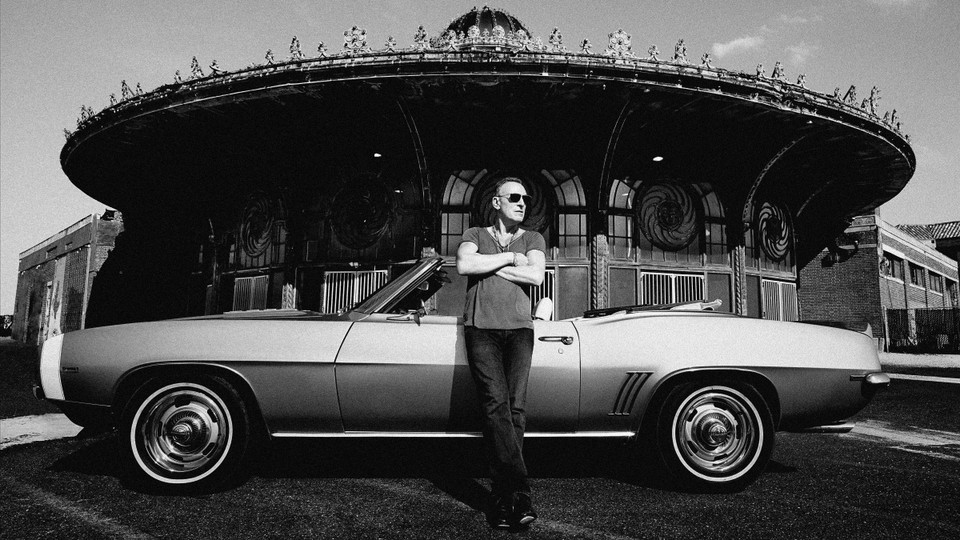

Meanwhile, he’s doing a few new things on Only the Strong Survive, or doing some things more overtly now. There’s a slickness and a swagger in his delivery that feel at times like acting the part of a cool operator, a hoary cliché of Black masculinity. In videos Springsteen produced for two of the early singles, he looks the part as well, dressed sharply in what appears to be a sharkskin suit packed with Detroit-by-way-of-Freehold muscle. Standing straight-backed without a guitar, he uses his hands in a set of calibrated gestures that I recognize from soul and gospel acts but have never seen Springsteen use before—he comes across like a gifted role-player in a role he hasn’t yet quite mastered.

This isn’t blackface, nor is it pure cultural appropriation. Springsteen clearly cares dearly for the music he is honoring in these earnest and highly skillful but fraught performances, and he’s not doing a parody of Black music. In the course of performing work of any tradition, it is his prerogative to draw liberally from the realm he is honoring. What he’s doing is performing, after all, and Springsteen, in recent years, has admitted to the falseness in his image as a blue-collar working man who never held a regular job, a hot-rodding motorhead without a driver’s license. “I come from a Boardwalk town where everything is tinged with just a bit of fraud,” he said in Springsteen on Broadway. “So am I.” It’s a confession that exonerates him while neatly complicating his image as an exemplar of authenticity.

And yet there remains something off-putting and simply off in this high-profile presentation of a successful white man singing Black music, even in ardent homage. It’s not pointedly wrong. It’s just pointless, because it adds nothing to our understanding or appreciation of the music—or of its singer. To fault Bruce Springsteen for loving soul music would be a slight to the music. He has every right to sing it. There’s just not much to be gained by listening.