If you're reading this, you're either on the fence about investing but haven't yet taken the plunge, or you have impeccable taste in authors.

Either way, I have something for you.

Once upon a time, I didn't invest. Happens to the best of us. And from the outside looking in, as a guy who (at the time) specialized in sports, not stocks, my first exposure to the investing world – my company 401(k) – left me completely intimidated.

It wasn't just the terminology and strategies I knew I didn't understand. It was the fact that investing was a real financial decision with real financial consequences.

Money was being taken out of my paycheck, and I had heard enough to know that sometimes investments just go really sour really quickly.

In other words, I thought there was a real risk I was flushing some of my hard-earned cash down the toilet.

I was locked and loaded with excuses and I dawdled for nearly two years. Knowing what I know now, I shouldn't have. I would've been better off had I immediately put my money to work.

But I can't turn back my clock – I can only help you make the most of yours.

If you're hesitant about jumping into investing, whether that's participating in your company's 401(k) or opening your own brokerage account, let me give you the gentle two-handed shove you need to get into gear.

I'll do that by knocking down five common excuses people make when they just can't seem to commit.

"I don't have enough time."

Au contraire, mon frère.

I can tell you firsthand that simply isn't true. In fact, you can probably get started in a fraction of one day's social media usage.

For years, I've helped review online brokerage firms. Many times, as part of a reviewing team, we're given a trial account that we can play around on. But in some instances, I've had to open and even fund accounts to dig in.

I have enough experience and reps that I can now fly through the application process, but even first-time investors can typically apply for, fund, and get started with a brokerage account in a mere 15 to 30 minutes.

And if you're investing through a company 401(k), the process is even quicker! There's no real application process – you enroll, log in and decide which retirement funds you want to buy with your future contributions.

However, if that's not enough to convince you, how about I help you visualize the idea of "time is money."

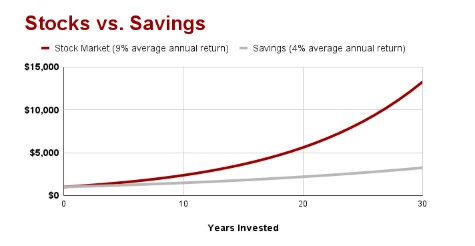

The gray line is what you can expect to earn from a mere thousand dollars stashed away in a savings account.

The red line? Those are the returns you'd historically expect (albeit with a touch more volatility, of course) by taking half an hour to open a brokerage account, stuffing a grand into an S&P 500 index fund, and never thinking about it again.

"I don't know how to open an account."

Here's something that should take a little pressure off: Most people who open a brokerage account for the first time don't know exactly how to do so until they do it! I know I didn't!

The good news? Brokers want you to open an account, so they try to make it easy by guiding you as you go and clearly explaining each step.

Also helpful? While every broker's sign-up process is at least a little different than the next, there are a lot of similarities, especially as it pertains to the information they need to collect from you.

Investor.gov provides a robust list of data you might be asked to provide, including (but not limited to):

- Name

- Social Security number or Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN)

- Date of birth

- Address

- Telephone number

- Email address

- Employment status

- Occupation

- Annual income

Past that, the brokerage might ask you questions about your risk tolerance and investment goals, whether you want to open a margin account, and how you want uninvested cash to be managed.

Once you're approved and the account is opened, you'll need to fund your account (which, again, your broker should guide you through).

From there, many brokers will have educational centers in case you want to learn a few basics before you get started. (We also have a few pieces of advice for beginners to start investing in the stock market.)

"I don't have enough money."

You do! In fact, at no time in history has investing been more affordable and accessible for people with only a few coins to rub together. Why?

Most brokerage accounts don't require a minimum deposit. Whether you have $1,000 to start with, $100, $10, or even $1, you have enough to open an account with a number of reputable providers.

Many stocks and funds are more affordable than you realize. Yes, some mutual funds require an initial investment of a few thousand dollars, and yes, some stocks and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) start at a few hundred dollars apiece. But many, many more stocks and ETFs trade for less than $100 per share – indeed, some cheap stocks trade for under $10 a pop! (Just don't go too crazy; penny stocks, while infinitely affordable, are a perilous playground.)

Some brokerages allow you to buy "fractional shares." If you have $50 in your pocket, but the stock you want trades at $100 per share, some brokerages will allow you to take that $50 and buy half a share. There'll still be a minimum dollar amount, but that minimum typically is as low as $5 or even $1!

"I don't know enough about investing."

Honestly, if this thought goes through your mind, I applaud you. Because in the 21st century, it's rare to find people who not only are self-aware enough to know what they don't know – but also are smart enough to understand that not knowing something could actually be problematic.

I also empathize: Again, I didn't get started when I should have because I was afraid I would make a boneheaded mistake in my 401(k).

Long term, you should take time to learn about how to make intelligent investments. But naturally, that advice won't do a lick of good in the here and now.

So if you just want to get started and you don't know much, take a cue from … well, 401(k)s.

Some 401(k)s will have a fund that's designated a "qualified default investment alternative (QDIA)." Should an employee contribute money to a 401(k) but not specify where that money should be allocated, rather than remain uninvested, that money will be automatically invested in the QDIA.

In many cases, the QDIA will be either a balanced fund (a mix of stocks and bonds) or a target-date fund (typically also a mix of stocks and bonds, but the portfolio is adjusted over time to suit the needs of investors as they get older).

These are effectively set-it-and-forget-it investments that provide you with exposure to both growth and income investments – perhaps not always the most ideal balance for you personally, but a more-than-adequate starting point for someone who simply wants to start the clock on their money.

If you have a 401(k), you'll want to see if you have a QDIA or investigate any target-date funds available in your plan. Alternatively, if you're just starting to invest in a brokerage account or individual retirement account (IRA) … well, you can buy balanced and target-date funds in those accounts too.

"The stock market is a casino."

I'll level with you: I've been doing this for more than a decade now, and still, every now and then … yeah, the stock market really does feel like a casino.

But I know it isn't actually a casino.

Why we feel this way can be a touch difficult to explain, but I'll give it a shot:

I have a phone in my pocket that lets me communicate with people across the world. It lets me check the weather, play games, check my heart rate history and dozens of other functions – and it's smaller and lighter than a brick. It sure feels like magic … but I know it's not.

If I'm breathing deeply and being calm and rational, I know that there's science behind my magical thin brick, even if I don't necessarily understand how that science works.

Now, let's apply this to the stock market.

There's this magical, nebulous place where I can take all of my money and suddenly turn it into a lot more money.

I could theoretically double my money in just a few hours … but I could lose it all just as quickly. And, using pai gow as part of this strained analogy, many times, money changes hands for reasons I simply don't understand. It sure feels like a casino.

But I know that there are legitimate financial, scientific, and even psychological reasons for why this happens, even if I don't always understand exactly how those things apply to every situation.

I realize that's a little touchy-feely, so I'll try to bring this home with a little practicality.

The stock market feels like it's a casino in part because we so often focus on big moves. Stock X gained 30%, Stock Y lost 40%. We hear about big moves all the time even though relatively boring moves are much more common in individual stocks.

And when you lump hundreds of those stocks together, as you do with indices such as the S&P 500 or Nasdaq Composite, those big moves are even rarer.

Consider this: Amid what is widely considered a historically volatile year, as of December 15, the stock market had 54 days where the S&P 500 moved more than 1%, up or down, in a single session. That's out of the 238 total trading days up to that point.

In other words, most of the time this year, the S&P 500 has only mustered a fractional move – and even when it did get a little lively, we're often talking about movement of, say, 1.5% or 2%.

When you think about it that way, it doesn't sound much like a casino at all, does it?

So if you're just getting started and you want to avoid the feeling like you're just putting all of your chips on black and hoping you boom instead of going bust, your best bet is to buy a few diversified funds and call it a day.

By holding several thousand stocks or bonds in just a handful of funds, you'll be less exposed to the big single-stock moves you read about, providing a smoother, digestible market experience.