Sea levels are rising, and that will bring profound flood risks to large parts of the Gulf and Atlantic coasts over the next three decades.

A new report led by scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration warns that the U.S. should prepare for 10-12 inches of relative sea level rise on average in the next 30 years. The rise is due to both sinking land and global warming. And given the greenhouse emissions released so far, the country is unlikely to be able to avoid it.

That much sea level rise means cities like Miami that see nuisance flooding during high tides today will experience more damaging floods by midcentury. Nationally, the report expects moderate coastal flooding will occur 10 times as often by 2050. Without significant adaptations, high tides will more frequently pour into streets and disrupt coastal infrastructure, including ports that are essential for supply chains and the economy.

The higher ocean will also bring seawater farther inland. By the end of the century, an average of 2 feet of sea level rise or more is likely, depending on how much the world its cuts greenhouse gas emissions.

As a geoscientist, I study sea level rise and the effects of climate change. Here’s a quick explanation of two main ways global warming is affecting ocean levels and their threat to the coasts.

Ocean thermal expansion

As greenhouse gases from fossil fuel use and other human activities accumulate in the atmosphere, they trap energy that would otherwise escape into space. That energy causes average global surface temperatures to rise, especially the upper layers of the ocean.

Thermal expansion happens when the ocean heats up. The heat causes sea water molecules to move slightly farther apart, taking up more space. The result is the ocean rises higher, flooding more land.

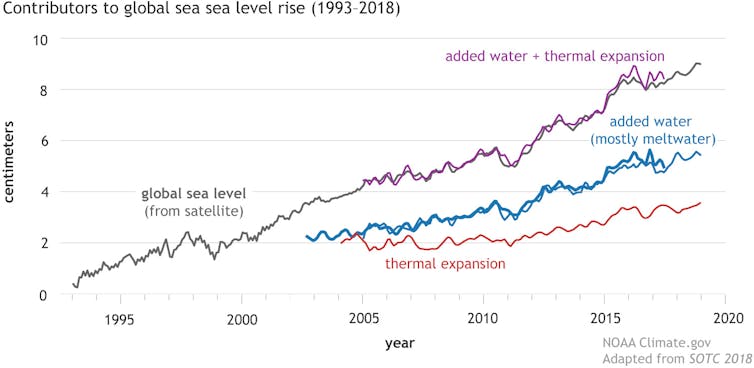

Over the past several decades, about 40% of global sea level rise has been due to the effect of thermal expansion. The ocean, which covers about two-thirds of the Earth’s surface, has been absorbing and storing more than 90% of the excess heat added to the climate system due to greenhouse gas emissions.

Melting land ice

The other major factor in rising sea levels is melting land ice. Mountain glaciers and polar ice sheets are diminishing at rates faster than natural systems can replace them.

When land ice melts, that meltwater eventually flows into the ocean, adding new quantities of water to the ocean and increasing the total ocean mass. About 50% of global sea level rise was induced by land ice melt during the past several decades.

Currently, the polar ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica hold enough frozen waters that if they melted completely, it would raise the global sea level by up to 200 feet, or 60-70 meters – about the height of the Statue of Liberty.

Climate change is melting sea ice as well. However, because this ice already floats at the ocean’s surface and displaces a certain amount of liquid water below, this melting does not contribute to sea level rise.

Risk will keep rising long after emissions stabilize

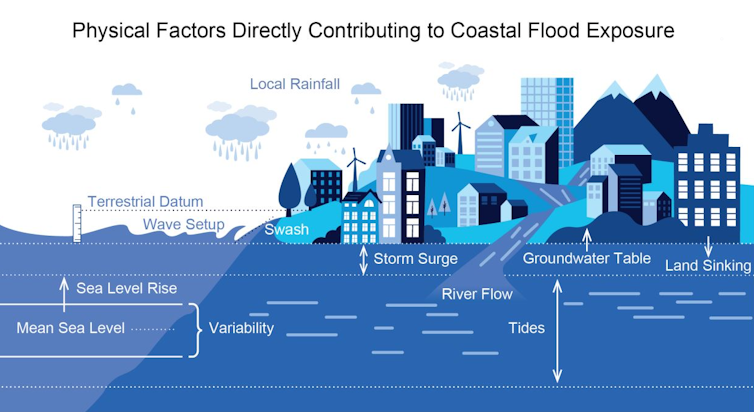

While the surface height of the ocean rises globally as the planet warms, the impact is not the same for every coastal region. The rate of rise can be several times faster in some places due to unique local conditions, such as shifts in ocean circulation or the subsidence of the land.

The U.S. East Coast and Gulf Coast, for example, face risks above the average, according to the new report, while the West Coast and Hawaii are projected to be lower than average.

Nearly 4 in 10 U.S. residents live near a coastline, and a large part of the U.S. economy is there, as well.

Even when greenhouse gas emissions eventually fall, sea level will keep rising for centuries because the massive ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica will continue to melt and take a very long time to reach a new equilibrium. A 2021 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change shows the excess heat already in the climate system has locked in the current rates of thermal expansion and land ice melt for at least the next few decades.

Jianjun Yin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.