Most tax-exempt nonprofits must file a 990 form with the Internal Revenue Service every year, typically in mid-May.

The 990 is purely informational. Nonprofits commit to serve an “approved purpose” – such as fighting bigotry, protecting animal welfare or sheltering the homeless – and meeting other eligibility rules. In exchange, they generally don’t pay taxes on the donations they receive or other sources of income. But they must file either this 12-page form or a shorter version of it, in which they report information about their finances, leadership and activities.

The IRS needs this information to verify that nonprofits should keep their tax-exempt status. It reviews 990s and selects some to audit, just as it does for individuals and businesses.

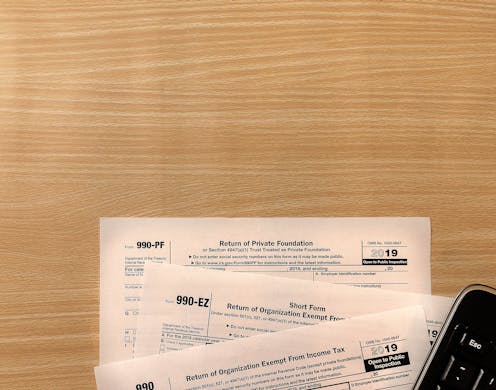

The 990’s formal title is “Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax.” Since 1941, these forms have given the IRS an overview of nonprofit finances, including revenue, expenses, assets and liabilities. The form sums up the group’s mission, indicates who sits on its board of directors and states highest-paid employees’ pay.

The most recent version discloses details regarding the group’s activities through answers to more than 80 questions. While charitable nonprofits file most 990s, other entities, such as nonexempt charitable trusts, private foundations and some political organizations, also must file them.

Why 990s matter

Because the government makes this data publicly available, organizations that assess the quality of a nonprofit’s operations and management, such as Charity Navigator, can analyze it. This helps the public assess whether the organization is trustworthy.

And prospective donors and others may easily access 990 forms, with help from “finder” features that groups like ProPublica and Candid maintain.

[More than 140,000 readers get one of The Conversation’s informative newsletters. Join the list today.]

When nonprofits fail to file 990s for three years in a row, the IRS automatically revokes their tax-exempt status. Those organizations may apply to have it reinstated by sending in a new application and paying a fee.

Shorter forms or none at all

There are at least 1.5 million U.S. tax-exempt nonprofits. Most need to file a 990 return, which they must do electronically.

Nonprofits with incomes below $200,000 and assets of less than $500,000 may file a shorter version of the form called the 990-EZ. The 990-EZ, which is four pages long, still requires the reporting of income and expenses. Because it asks fewer questions, completing the 990-EZ requires less disclosure.

Nonprofits with incomes of $50,000 or less may file even simpler paperwork: the 990-N form. Often called an e-postcard, the 990-N requires the reporting of minimal information. It simply verifies that the nonprofit still exists and can continue to be tax-exempt.

Private foundations and similar groups file the 990 PF, on which they report any tax due on investment income. There’s also a 990-T, for nonprofits with taxable business income.

One large group of tax-exempt nonprofits isn’t required to file 990s: churches and other faith-based organizations engaged in worship.

Read other short accessible explanations of newsworthy subjects written by academics in their areas of expertise for The Conversation U.S. here.

Sarah Webber does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

.jpg?w=600)