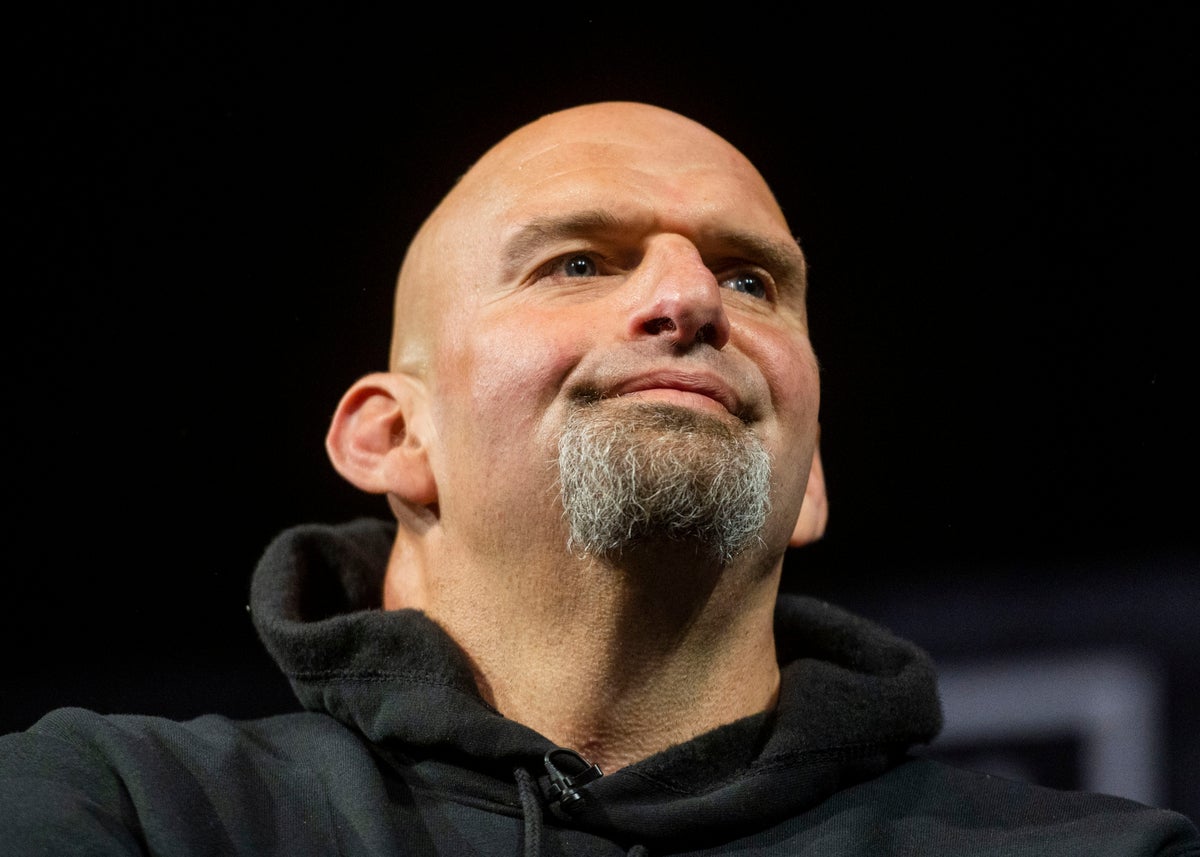

Starting this week, a super PAC that supports Pennsylvania Republican Senate candidate Dr Mehmet Oz will be running a $1.5m ad buy highlighting a highly controversial moment in the life of his rival, progressive Democrat John Fetterman.

In 2013, while Mr Fetterman, the current Pennsylvania lieutenant governor, was serving as mayor of the town of Braddock, he chased an unarmed Black jogger with his car and stopped him at gunpoint, thinking he’d heard gunshots nearby and the man might be responsible.

“My message to Black voters: Do your homework about John Fetterman,” says a narrator in the ads, paid for by the Republican Jewish Coalition’s political action committee. “He didn’t even apologise. And now he wants our vote? Not a chance.”

The videos are expected to air mainly in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, cities with substantial Black populations, and are an explicit attempt to peel off African-American support for Mr Fetterman, who has run on his progressive politics and record working to end gun violence in predominantly Black Braddock.

The lieutenant governor’s critics on both the left and right have used the 2013 incident to attack Mr Fetterman’s bona fides. Here’s what you need to know about what happened.

In 2013, Braddock police responded to reports of gunshots in the area near Mr Fetterman’s home.

According to Mr Fetterman, he was outside in his yard with his four-year-old son at the time. In a 2022 campaign video about gun violence, the lieutenant governor said he thought the gunshots came from the direction of a nearby school and was worried about another attack like the Sandy Hook Elementary massacre.

He saw a jogger, Christopher Miyares, running by in dark clothes and a face mask, and feared he could be responsible, so Mr Fetterman grabbed his shotgun, chased the man in his truck, and detained him until police could arrive.

“I realised I could never forgive myself if I didn’t do anything,” Mr Fetterman says in the video.

The jogger was found to be unarmed, according to police reports.

“I believe I did the right thing,” Mr Fetterman told a local news station in 2013. “But I may have broken the law in the course of it. I’m certainly not above the law.”

Miyares, who is Black, has a very different version of events. In his telling, Mr Fetterman chased after him and threatened him with fatal violence because of his race.

He told the Philadelphia Inquirer in a 2021 letter from state prison, where he is incarcerated on unrelated charges, that the lieutenant governor “lied about everything” in regards to the 2013 event.

Miyares says the gunshots the mayor heard were just kids firing off bottle rockets. (Mr Fetterman said Miyares invented this detail.)

“He knew my race,” he wrote. “The gun was aimed at my chest.”

Mr Fetterman has said that because of Miyares’s face mask, he wasn’t aware of the man’s race.

Nonetheless, Miyares, who never pressed any charges or filed a complaint against Mr Fetterman, said in the letter it “is inhumane to believe one mistake should define a man’s life” and that the lieutenant governor has his support.

“Mr Fetterman and his family have done far more good than that one bad act or action and, as such, should not be defined by it,” Miyares concluded.

The 2013 incident has cast a long shadow over the political ambitions of Mr Fetterman, who has made public safety and reducing gun violence in working-class Black communities like Braddock a key part of his agenda. He has the dates of murders in the town tattooed on one of his arms.

“I put the dates of people that were taken by violence in my community as mayor because I never saw the media or the public at large caring about those lives,” he said in the campaign video. “Black lives mattering and these communities mattering.”

As mayor of Braddock, he worked with community leaders in the town’s Black population on a community policing plan, and during the 2020 racial justice protests after the killing of George Floyd, he wrote an op-ed calling for police officers to “fall on the side of de-escalation every time” rather than resort to violence during stops.

Nonetheless, critics argue the 2013 incident shows these commitments to racial allyship and reducing violence only go so far, and faulted Mr Fetterman for not making a full apology.

Other Republican groups have called attention to the 2013 incident during the Senate campaign, and so have Democrats.

They point to the interaction as a frightening instance of white vigilantism, a behaviour that can have fatal consequences. In chillingly similar circumstance in 2020, a group of armed white men chased Black jogger Ahmaud Arbery through a Georgia town in their truck then shot him to death, claiming they thought he was responsible for a recent break-in.

“I don’t think this is about whether John is racist. I’ve not known him to be,” Malcom Kenyatta, a Pennsylvania state representative who ran against Mr Fetterman in the Democratic primary for Senate, told the Inquirer this year. “But I don’t think we can have a system in Pennsylvania where somebody thinks they hear something and then have carte blanche to go chase down the next person they see with a shotgun. I’m from North Philadelphia. I hear gun shots all the time, unfortunately, but we can’t have people think they hear something and run and confront the next person they see. ... As a young Black man I know how traumatising that can be.”

Another Senate rival, Democrat Conor Lamb, also hit out at Mr Fetterman over the incident, calling it “the elephant in the room”.

In 2020, Donald Trump Jr resurfaced a local news video about the incident to his millions of followers.

“I’m not going to just sit here while a bunch of Republicans who have never given a damn about racial justice launch these bad-faith attacks from the safety of their gated communities,” Mr Fetterman said in a statement at the time. “They’ve never had stray bullets hit their home, or had a bullet whiz by so close that you can feel the air move. When I ran for mayor, I made a commitment to do whatever I could to confront this gun violence — and that’s exactly what I’ve done.”

How much the 2013 incident, or the ads bringing it back to light, impacts Mr Fetterman’s campaign remains to be seen. He was re-elected in Braddock, whose population is mostly Black, shortly after the encounter, and only 11 per cent of Pennsylvania voters are Black.

A USA Today-Suffolk University poll released Tuesday shows Mr Fetterman with a six-point lead over Dr Oz.

A September poll found that Mr Fetterman has a clear lead among Black voters in Pennsylvania, with 65 per cent support.