COP27 has some of the most authoritarian security of any of the COP summits. Set in the walled resort of Sharm el-Sheikh in Egypt, it is surrounded by 36km of concrete and razor wire, overseen by new surveillance technologies and a “security observatory”.

Protesters are also restricted to a distant site in the desert. Protest has been effectively prohibited in Egypt since the 2013 coup when the retired military general, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, overthrew his country’s democratically elected Islamist President, Mohammed Morsi, amid mass protests against his rule. Donald Trump once referred to the Egyptian president as his “favourite dictator”.

Like Egypt, Qatar, the host country for this year’s World Cup, also has a long history of human rights abuses. Indeed, the decision to hold the World Cup in Qatar has been criticised by many, especially LGBT+ groups as homosexuality can be punishable by death.

Both Qatar and Egypt are countries that are classified as “not free” by Freedom House, a US government-funded human rights group. And yet, despite civil liberties, including press freedom and freedom of assembly, being tightly restricted, over the past decade, both countries have received weapons licensed by the UK government.

Indeed, 2021 analysis from the Guardian and Campaign Against Arms Trade (CAAT), a UK-based organisation working to end the international arms trade, found that 21 out of 30 countries on the UK government’s list of repressive regimes had received UK military equipment. And that between 2011-20, the UK licensed £16.8 billion of arms to countries that have been criticised by Freedom House. The government did not respond to the Guardian’s investigation.

Bombs, fighter jets and tanks

Arms production is a vast global business. And many governments are implicated, hosting arms fairs, brokering international deals and issuing export licenses. France, for example, is one of Egypt’s largest suppliers of weapons, exporting warships, fighter jets, armoured vehicles and surveillance systems suitable for intercepting communications and controlling social movements.

Britain has also sold Egypt and Qatar surveillance equipment, machine guns and combat vehicles.

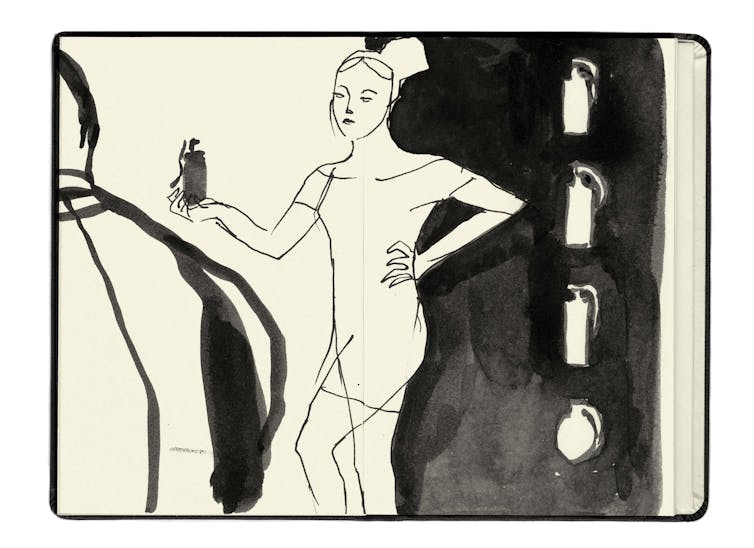

I have visited arms fairs for over ten years. I get through security by describing myself as a defence consultant, then draw and collect marketing material. The most recent one I went to, Eurosatory, was held in June 2022 in Paris. It is one of the world’s largest arms fairs and an international gathering of politicians, dictators, civil servants and corporations.

Arms fairs may receive less press attention than COP meetings or the World Cup but they perhaps give a clearer indication of governments’ global priorities.

At Eurosatory, arms companies from around the world display missiles, bombs, fighter jets and tanks to an international clientele. Since the Arab spring, there has also been a section for crowd control euphemistically called “less lethal” weaponry.

Mannequins tower over the visitors, wearing armour, digital helmets and gasmasks, aiming guns, batons, shields and grenades. Cabinets display teargas, rubber bullets and stun grenades in neat clinical rows. One cabinet has the curiously named “moral effect grenades”. There are also drones, armoured police cars, surveillance systems and listening technologies. Sales staff demonstrate products and offer wine.

Batons, shields and grenades

Like any trade show, arms fairs have complimentary gifts - pens, sweets and stress-balls, except here they are based on weapons.

This year, there were stress-balls in the shape of grenades, camouflage ducks, catalogues showing crowds running away from police spraying teargas, and alongside this, key fobs with metallic representations of people running. Trapped on the ring, metal glinting under spotlights, the running figures show how arms companies treat repression as a sales opportunity.

The UK Defence and Security Exports Department has identified both Egypt and Qatar as “key markets” and the UK government regularly invites both countries to the London arms fair, DSEI (Defence and Security Equipment International).

Instead of tightening arms export controls for countries with dire records on human rights and civil liberties the UK government plans to relax them. I visited DSEI in September 2021 and listened as the defence secretary Ben Wallace promised closer ties between the government, arms companies and their clients.

“We’re making it easier for you to get an export licence by unblocking the approval bottlenecks,” Wallace said. He also promised, that “they will be underpinned by robust accountability and always put the needs of the customer front and centre”.

Both promises seem rash when customers include leaders like Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. Indeed, there can be no global security while governments are in the thrall of an industry that uses repression as a source of profit. Or while they continue to sell arms to countries that imprison activists rather than listen to them.

Jill Gibbon receives funding from the ISRF.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.