For the past 25 years, NASA's flagship Chandra X-ray Observatory has recorded X-ray emissions from exploded stars, supermassive black holes, galaxy clusters and other exotic, high-energy pockets of our universe, allowing scientists around the world to piece together the structure and history of our cosmos.

As part of the telescope's anniversary celebrations this week, the space agency released a behind-the-scenes look at the work it takes to keep the $1.5 billion spacecraft flying in space, and of its workforce of engineers, technicians, analysts and designers, many of whom have been involved in the mission since its inception decades ago.

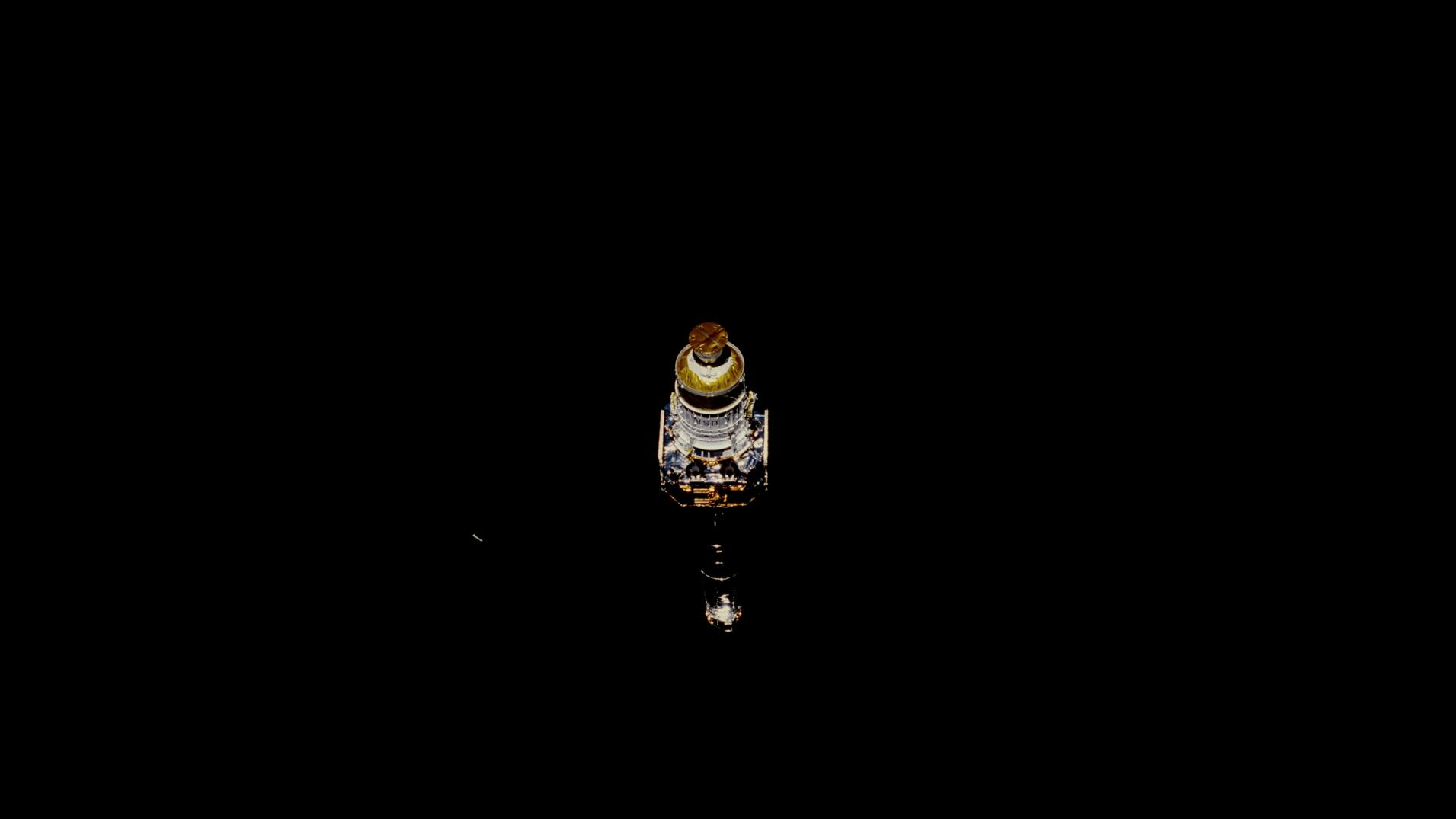

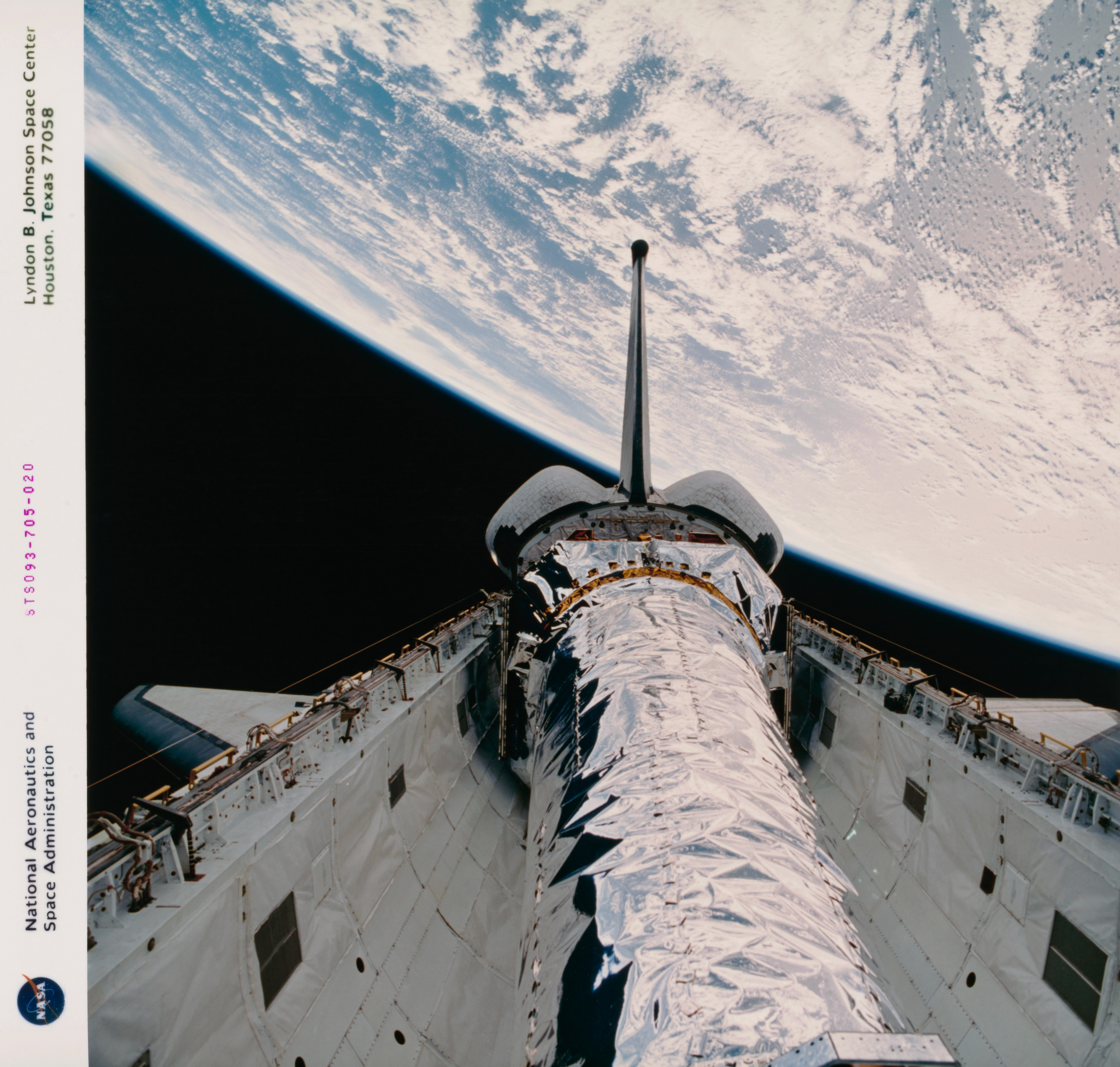

The Chandra telescope was first proposed to NASA in 1976, and funding and preliminary work began a year later. The endeavor was led by the Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Massachusetts, which is also now responsible for the day-to-day operations of the telescope. The telescope launched into space aboard the space shuttle Columbia in 1999 and was placed into an orbit that took it one-third of the way to the moon. From its vantage point, Chandra has helped astronomers study mysteries they didn't even know existed when it was being built, including the intricacies of exoplanets and dark energy.

"How much technology from 1999 is still in use today?" Douglas Swartz, a Chandra researcher, said in a recent NASA statement. "We don't use the same camera equipment, computers, or phones from that era. But one technological success – Chandra – is still going strong, and still so powerful that it can read a stop sign from 12 miles away."

The mission, which was initially designed to last five years and then extended to at least 10, still has a decade of life left. The lasting value is no accident, according to the mission team, which automated aspects of the observatory to improve its efficiency. After Chandra's budget was reduced in 1992, the mission was dramatically restructured to remove the planned servicing and upgrades by visiting astronauts while minimizing changes to its science output. "There was a lot of excitement and a lot of challenges — but we met them and conquered them," project engineer David Hood, who joined the Chandra development effort in 1988, said in the statement.

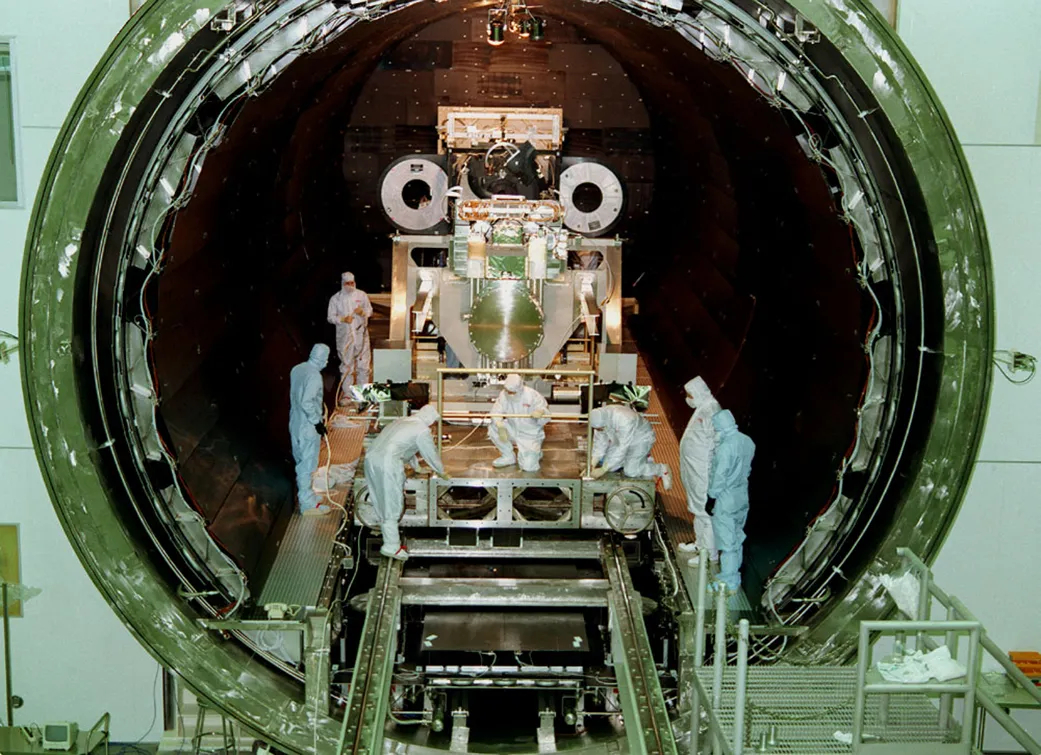

"The field of high-powered X-ray astronomy was still so relatively young, it wasn't just a matter of building a revolutionary observatory," Martin Weisskopf, who led Chandra scientific development starting in the late 1970s, said in the statement. "First, we had to build the tools necessary to test, analyze, and refine the hardware."

Marshall renovated and expanded its X-ray Calibration Facility in Alabama to accommodate Chandra's instruments and test key hardware in a space-like environment — efforts that, years later, paved the way for testing the James Webb Space Telescope, which was designed as a successor to the Hubble Space Telescope.

The mission team now closely monitors the telescope's position in orbit and efficiency of its key instruments, like thermal insulation on its exterior that has unsurprisingly degraded over time thanks to the harsh space environment, preventing the telescope from staring in one direction for too long. While operating the telescope has gotten more complicated, scientists insist observational efficiency has remained as high as it was at the mission's start.

"Chandra's still a workhorse, but one that needs gentler handling," Jodi Turk, a thermal analyst at the Marshall Space Flight Center, said in the statement.

The 25th anniversary of the iconic telescope is bittersweet for many astronomers, who worry the telescope will be shut down prematurely after NASA in its fiscal year 2025 budget proposal, which was released in March, slashed Chandra's funding by 40 percent due to budget pressures — from $68.3 million in 2023 to $41.1 million for next year, and with further drops after 2026 that reduce its funding to just $5.2 million by 2029. The loss of the Chandra telescope would be an "extinction-level" event for X-ray astronomy in the U.S., with no other telescope that mirrors or surpasses Chandra's capabilities. Over a 100 astronomers continue to urge NASA to reconsider its decision via a "Save Chandra" coalition, arguing that the observatory has had stable operational costs over the past decades and still has a decade of life left.

Yesterday (July 23), a NASA committee tasked with exploring ways to reduce operational costs for Chandra concluded there isn't a way to continue operating the observatory at the reduced funding proposed by NASA, SpaceNews reported. The committee also outlined three options that would keep Chandra running with decreased capabilities, such as limiting its observing programs to those that have synergies with other telescopes, but all three possibilities would require budgets higher than what NASA has proposed.

NASA is currently reviewing these options and aims to announce its plans for changes to Chandra in mid-September.