Rishi Sunak’s plans to tackle illegal migration to the UK have passed their first parliamentary hurdle, gaining the support of MPs in the Commons by 289 votes to 230.

The government accepted several amendments from rebel Conservatives, including clarifying the limited circumstances in which unaccompanied children could be deported and a commitment to set out the “safe and legal routes” for asylum seekers to reach Britain.

But other government amendments toughened the law, making it harder for those who are deported to seek a waiver of their ban on re-entry or gaining British citizenship, and limiting the ability of individuals to delay their removal to a third country by citing the risk of “serious and irreversible harm”.

Mr Sunak has made stopping small boat arrivals one of his five key priorities and the Illegal Migration Bill will mean anyone who arrives on small boats will be prevented from claiming asylum and deported either back to their homeland or to so-called safe third countries.

The plans include a near-half-a-billion-pound plan with France, to help fund a new detention centre near Dunkirk, more drones and an extra 500 police officers to prevent migrants making the dangerous journey across the English Channel.

Mr Sunak said the legislation was needed to stop people from making the treacherous journey across the English Channel and making what he described as bogus asylum claims.

Britain is already sending money to France to tackle the issue and has spent some £250m doing so since 2015, but the numbers coming to the UK have continued to rise.

The Labour Party has branded the new bill a “con” and another “gimmick” that it claimed would not work. The United Nations said the plan would break international law.

How many people have come to the UK on small boats?

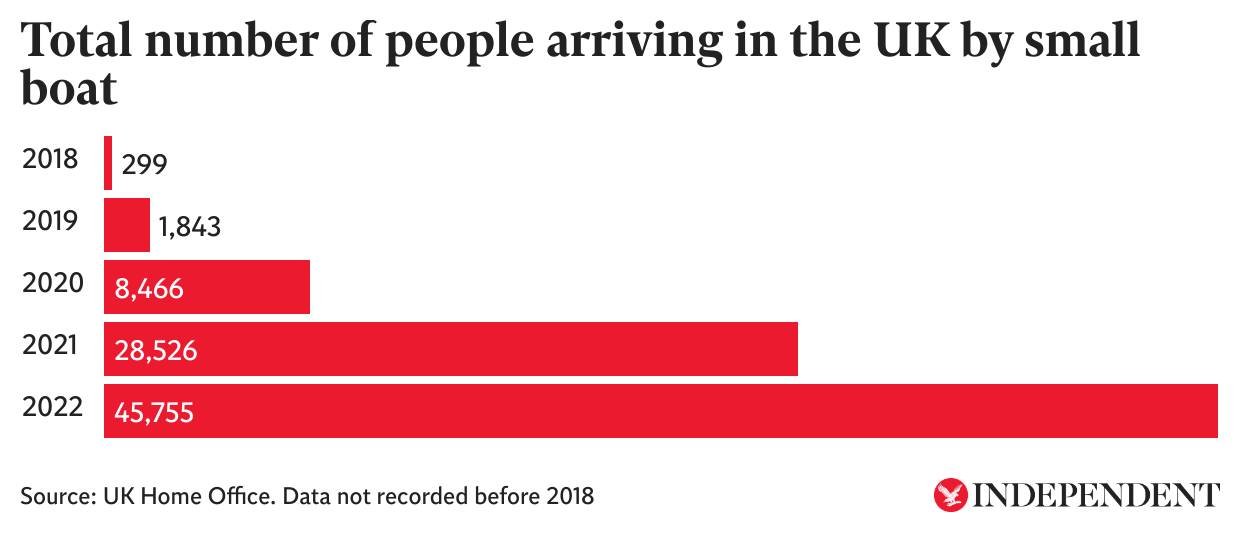

Some 85,889 people arrived in the UK by small boat between January 2018 and December 2022, according to official figures. 3,150 arrived between 1 January and 7 March 2023.

The government began recording data in 2018 due to a spike in the number of people making the trip across the English Channel, most of whom set out from France.

Britain already sends money to France to tackle the issue and has spent some £250m doing so since 2015, but the numbers coming to the UK have continued to rise.

Analysts say the spike in numbers is due in part to increased security at the UK’s land borders, making it more difficult for people to reach the UK in lorries.

Are the numbers going up?

Yes. The number of people arriving in the UK has been steadily increasing every year since 2018 and grew by 60 per cent between 2021 and 2022.

In 2018, 299 people arrived in the UK on small boats. This increased to 1,843 in 2019, 8,466 in 2020, 28,526 in 2021 and 45,755 in 2022.

Which countries are people coming from?

According to the Home Office, Iranians have accounted for 22 per cent of all small boat arrivals since 2018.

People from Iran represented the majority of small boat arrivals in 2018 (80 per cent) and in 2019, 66 per cent.

“However,” the Home Office added, “a greater mix of nationalities have been detected making the crossing since 2020. Albanian and Afghan nationals became noticeably more common in 2022.”

In 2022, almost half of all small boat arrivals were from these two nationalities – Albanians, 28 per cent, and Afghans, 20 per cent.

More than 12,000 people have arrived from Iraq since 2018.

What happens when people arrive in the UK on small boats?

According to the Home Office, most people who arrive in the UK by small boat claim asylum. There have been 76,134 such applications since January 2018.

Under the current system, asylum seekers who reach the UK are often able to remain in the country while their claims are assessed.

Government figures showed there were more than 160,000 of these claims waiting to be processed at the end of last year.

Under British law, you must be physically present in the UK in order to claim asylum. There is no visa for people to travel to the country for that purpose, meaning that they must arrive by different means.

Most asylum seekers arrive in the UK through legal travel, such as commercial flights, on visas for other purposes such as tourism or study.

But those who are unable to obtain visas because of their practical or financial situation, such as fleeing a war zone or hostile government, are pushed onto irregular and illegal routes often controlled by smuggling gangs.

Because of the Schengen passport-free area inside the EU, many asylum seekers heading for the UK make irregular sea journeys to Greece or Italy and then travel over land until their journey ends on France’s northern coast.

To be eligible to claim asylum “you must have left your country and be unable to go back because you fear persecution”.

The government says this persecution must be because of your race, religion, nationality, political opinion or “anything else that puts you at risk because of the social, cultural, religious or political situation in your country, for example, your gender, gender identity or sexual orientation”.

People applying for asylum in the UK must have failed to get protection from authorities in their own country.

Those who have their claims rejected will be asked to leave the country, although they can challenge the decision in the courts.

Where do people get sent if they are rejected?

People whose claims are rejected will be given the option to leave the country themselves and may get help with returning home, the government says.

Those who refuse to leave risk being detained without warning and taken to the immigration removal centre before being deported.

The UK lost the right to return migrants to EU countries after Brexit.

Those who have their claims rejected could eventually be sent to Rwanda following a deal between the two governments, or another “safe third country”.

The ‘Rwanda scheme’ was set up under the Nationality and Borders Bill – the government’s previous plan to tackle the issue.

But the scheme has failed to start, having been beset by legal challenges, and Albania is the only other nation to have agreed to accept asylum seekers from the UK.

What are the current safe and legal routes to asylum?

The government says it operates several safe and legal immigration routes. These are:

- The UK Resettlement Scheme, Community Sponsorship, and the Mandate Scheme are refugee resettlement programmes

- Refugee family reunion visas are available to immediate relatives of people granted refuge in the UK before they left their country of origin (known as pre-flight relatives)

- Nationality-specific bespoke immigration routes are available to some Afghans, Ukrainians, and people from Hong Kong

Ministers have hailed the arrival of hundreds of thousands of people from Ukraine and Hong Kong, but the schemes involved in those two instances have bypassed asylum processes with the creation of bespoke visas that do not grant refugee status.

The “safe and legal” routes the government claims those crossing the Channel ignore are programmes where the UK resettles people from abroad who are recognised by the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR). It also allows people to join relatives who have already been granted asylum in the UK.

They effectively allow the government to pick and choose who comes to the UK, how and when.

For that reason, the process is slow and extremely restricted.

The UNHCR has said: “Critical resettlement schemes remain very limited, and can never substitute for access to asylum. The Refugee Convention explicitly recognises that refugees may be compelled to enter a country of asylum irregularly.”

What is the new bill?

The government wants to deport any asylum seekers who arrive in the UK by small boats without first considering their case.

The bill puts a duty on the home secretary to arrange the removal of people who have come to the UK without permission if they have not arrived directly from a country where their liberty is at risk.

Suella Braverman, the current home secretary, said in a statement that the bill would “allow us to stop the boats that are bringing tens of thousands to our shores in flagrant breach of both our laws”.

Ms Braverman said that the bill would tackle the backlog in asylum applications, which has risen to 160,000.

The House of Commons approved the third reading of the bill by 289 votes to 230. It now passes to the House of Lords, where it could be amended or delayed.

Two amendments proposed by Conservative lawmakers – one to remove the power to deport children before they turn 18 altogether and one to exempt victims of unlawful exploitation in Britain from removal – were withdrawn after the government said it would look at ways to do more on the issues raised.

What do the critics say?

On the very first page of the bill, Ms Braveman said that she was unable to “make a statement that, in my view, the provisions of the Illegal Migration Bill are compatible with the Convention rights, but the government nevertheless wishes the House to proceed with the Bill”.

Ms Braverman meant that she was not sure whether or not the Illegal Migration Bill would breach human rights law.

The United Nations has since said that the plan would be a “clear breach” of international law.

What about the opposition?

The Labour Party has said it wants to tackle illegal migration too but could not support the bill because it would not work. The party said it would focus on tackling people-smuggling gangs organising boat crossings.

The UK has a number of migrant detention centres which are full, or close to being full, and the government has not yet set out how it plans to increase capacity.

Labour has said the plan would cause a spike in the use of hotels to house people awaiting asylum decisions, claiming that this could cost the taxpayer as much as £25bn over the next five years.

After Ms Braverman said some of the migrants arriving by small boats had values “at odds” with those of Britain, Labour said: “It’s pretty clear when you see politicians reaching for that sort of invective that it’s a sign that the policies that they are promoting have failed.”

Yvette Cooper, the shadow home secretary, said: “This Bill is a con. It will mean thousands more people in asylum accommodation indefinitely, with the taxpayer footing the bill because of the combination of their new law and their failure on returns.”

Labour leader Keir Starmer said at Prime Minister’s Questions on Wednesday that 18,000 people were deemed ineligible for asylum last year and that fewer than 1 per cent of them had been returned.

Modern slavery

Some have raised concerns that the government’s bill will fail people arriving on small boats who have legitimate claims to asylum, such as those who are victims of modern slavery and human trafficking.

According to the government’s own statistics, between 2018-2022, seven per cent of those arriving by small boats claimed to be modern slavery victims.

Of those, 85 per cent have received a positive reasonable grounds decision, meaning they are granted protection.

Will the plan work as a deterrent?

Some analysts have suggested that the true aim of the government’s plan is to act as a deterrent to those who want to come to the UK looking for a better life.

For many asylum seekers, large numbers of whom have fled war-torn countries, crossing the English Channel is only the final leg of a journey that has, in some cases, lasted for years,

Hundreds of people have already died attempting to make the treacherous crossing.

And some of those trying to make it have already been beaten, abused and detained on their way to the UK.

"If they send us away we will come back," Jaber, a 19-year-old Afghan told Sky News earlier this week when asked what he thought about the government’s new plan and whether it would work.

"And if they send me to Rwanda, I haven’t committed a crime, so I will come back,” he added, speaking from a camp in northern France, where overnight temperatures hovered around zero.