Ever been in love? You’ll know the rush. That’s chemistry at work. Our brain produces molecules such as 2-phenylethylamine, the mood enhancer also found in chocolate. But eating chocolate won’t make you fall in love – enzymes in your liver break it down before it gets to the brain. Chemistry does explain why certain drugs produce similar mood-enhancing effects and also why they can become a problem.

With a structure closely related to phenylethylamine, pure crystalline methamphetamine was first made in 1919 and its cousin, amphetamine, in 1887. Smith, Kline and French marketed a nasal inhaler containing amphetamine (“Benzedrine”) for nasal congestion in 1932; people soon found that it rapidly released stimulating neurotransmitter molecules such as dopamine. Within a short while, people were extracting it from the wadding in inhalers for its “high”, becoming known as “bennies”. Methamphetamine was also found to be a stimulant. Users felt sharper, stronger and more energetic.

Unlike cocaine, morphine (easily converted into heroin) and khat, which are plant-derived, methamphetamine is a synthetic drug. Similar molecules have been found in one or two plants, but there’s no evidence that they actually contain amphetamine or methamphetamine. While the plant-based drugs are widely smuggled across borders, methamphetamine can be made locally with cookbook recipes from the internet, using chemicals that can be bought on the high street or the internet.

Amphetamine and methamphetamine have a slightly different structure to the naturally occurring phenylethylamine (PEA), so they resist the liver enzyme that decomposes amines, such as phenylethylamine, in food. The body hasn’t yet developed enzymes to break down amphetamines, which have only been around for about 100 years.

Use … and addiction

During the second world war, methamphetamine, in particular, was used by both the Allied and the Axis powers - the Germans, Japanese, Americans and British - by watchkeepers on ships and bomber crews to keep alert on long night missions. In Germany, amphetamine was known as Pervitin (it is still called that in the Czech Republic).

Civilians used amphetamines, too. Author Graham Greene used Benzedrine in 1938 to complete his novel The Confidential Agent in six weeks; Jack Kerouac was said to have produced On the Road in one three-week frenzy of typing in April 1951. Benzedrine helped former British prime minister Anthony Eden get through the Suez crisis in 1956, though it may not have improved his decision-making.

Because of the energy rush they give, sportsmen also used amphetamines long before they turned to steroids, and they were banned from the Olympics in 1967. Tom Simpson, the first British cyclist to crack Europe (and wear the Yellow Jersey), and a BBC Sports Personality of the Year, long before media celebrities, died from a combination of heat, alcohol and methamphetamine on the 1967 Tour de France. However, their use continues, with the drug being cited in a number of doping scandals.

The first big amphetamine abuse occurred just after WWII in Japan. After 1951, they became prescription drugs in the US, widely prescribed as pick-me-ups, known as “pep pills”. Long-distance lorry drivers and students both used amphetamines to help stay awake and concentrate. A side-effect of amphetamines is appetite loss, so post-war they were also widely used as prescription drugs to fight obesity.

Because of its “go-faster” characteristics, methamphetamine started to be known as “speed” in the early 1960s. The Summer of Love in the Haight-Ashbury region of San Francisco in 1967 was fuelled by marijuana and psychedelics, such as LSD, but the next year things went badly wrong with an epidemic of intravenous methamphetamine injection; “peace and love” was replaced with the motto “speed kills”.

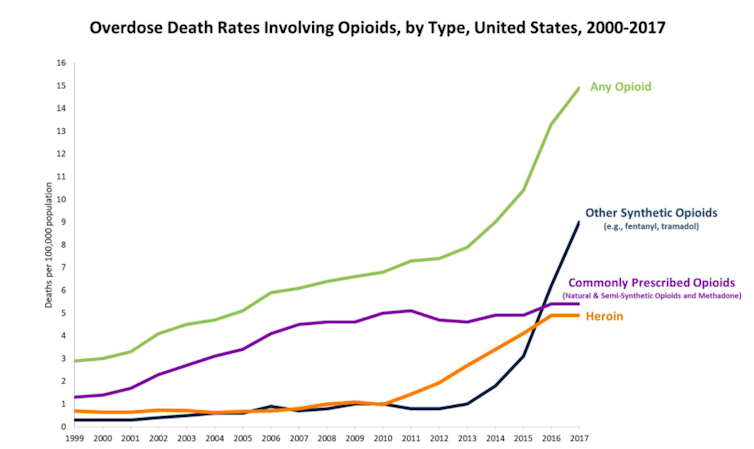

By the 1980s, someone in the Far East found out how to create large crystals of methamphetamine hydrochloride known as “crystal meth”, which did not have to be injected. Since then it has spread from Hawaii to the West Coast of America. In Thailand, it’s called Ya ba (“madness drug”). Although opioids are the biggest cause of drug death in the US, methamphetamine is a particular problem in its western and south-western states. In some ways it has become a forgotten epidemic.

A powerful stimulant, crystal meth has been linked with brain damage.

Two mirror-image forms

Methamphetamine molecules can exist in two mirror-image forms, which interact differently with the receptors in the human body.

The stimulant we call speed is d-methamphetamine; the other, l-methamphetamine, contains the same atoms connected in the same sequence, just arranged differently in space, and has absolutely no stimulant properties. It is simply a decongestant, found in American Vicks (not the British version). Olympic regulations, however, just forbid the use of “methamphetamine”. They do not distinguish between these two forms. Nor did the testing procedures used at the 2002 Winter Olympics, when Alain Baxter lost a medal for using an American Vicks.

Until now, methamphetamine – or crystal meth – has not really appeared in the UK drug market. Many will only be familiar with it from its use in the US series, Breaking Bad. But some fear that is about to change. Partly because of its cost, a plethora of alternatives, lack of availability of chemicals to make it, as well as a poor image, methamphetamine has not been fashionable in the UK for many years but it would be unwise to assume that this will continue.

Simon Cotton does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.