While ransomware incidents have been occurring for more than 30 years, only in the last decade has the term “ransomware” appeared regularly in popular media. Ransomware is a type of malicious software that blocks access to computer systems or encrypts files until a ransom is paid.

Cybercriminal gangs have adopted ransomware as a get-rich-quick scheme. Now, in the era of “ransomware as a service”, this has become a prolific and highly profitable tactic. Providing ransomware as a service means groups benefit from affiliate schemes where commission is paid for successful ransom demands.

Although only one of the many gangs operating, LockBit has been increasingly visible, with several high-profile victims recently appearing on the group’s website.

So what is LockBit? Who has fallen victim to them? And how can we protect ourselves from them?

What, or who, is LockBit?

To make things confusing, the term LockBit refers to both the malicious software (malware) and to the group that created it.

LockBit first gained attention in 2019. It’s a form of malware deliberately designed to be secretly deployed inside organisations, to find valuable data and steal it.

But rather than simply stealing the data, LockBit is a form of ransomware. Once the data has been copied, it is encrypted, rendering it inaccessible to the legitimate users. This data is then held to ransom – pay up, or you’ll never see your data again.

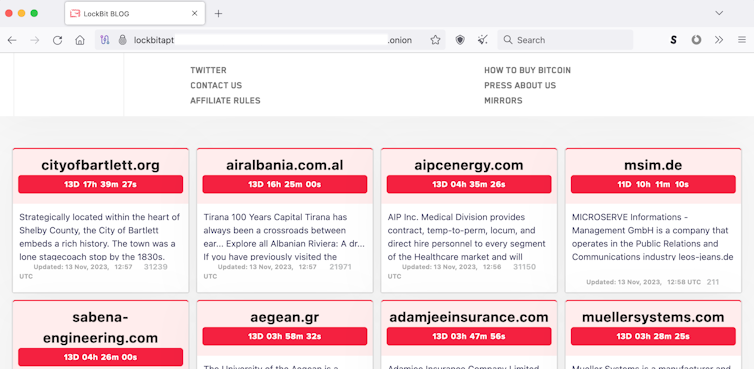

To add further incentive for the victim, if the ransom is not paid, they are threatened with publication of the stolen data (often described as double extortion). This threat is reinforced with a countdown timer on LockBit’s blog on the dark web.

Little is known about the LockBit group. Based on their website, the group doesn’t have a specific political allegiance. Unlike some other groups, they also don’t limit the number of affiliates:

We are located in the Netherlands, completely apolitical and only interested in money. We always have an unlimited amount of affiliates, enough space for all professionals. It does not matter what country you live in, what types of language you speak, what age you are, what religion you believe in, anyone on the planet can work with us at any time of the year.

Notably, LockBit have rules for their affiliates. Examples of forbidden targets (victims) include:

- critical infrastructure

- institutions where damage to the files could lead to death (such as hospitals)

- post-Soviet countries such as Armenia, Belarus, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan.

Other ransomware providers have also claimed they won’t target institutions like hospitals – but this doesn’t guarantee victim immunity. Earlier this year a Canadian hospital was a victim of LockBit, triggering the group behind LockBit to post an apology, offer free decryption tools and allegedly expel the affiliate who hacked the hospital.

While rules may be in place, there is always potential for rogue users to target forbidden organisations.

The final rule in the list above is an interesting exception. According to the group, these countries are off limits because a high proportion of the group’s members were “born and grew up in the Soviet Union”, despite now being “located in the Netherlands”.

Read more: Putin's Russia: people increasingly identify with the Soviet Union – here's what that means

Who’s been hacked by LockBit?

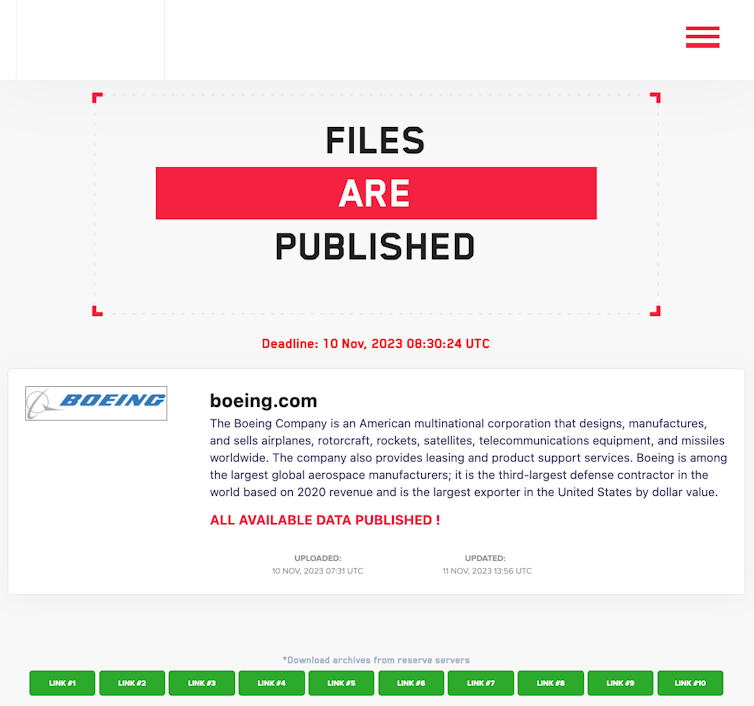

High-profile victims include the United Kingdom’s Royal Mail and Ministry of Defence, and Japanese cycling component manufacturer Shimano. Data stolen from aerospace company Boeing was leaked just this week after the company refused to pay ransom to LockBit.

While not yet confirmed, the recent ransomware incident experienced by the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China has been claimed by LockBit.

Since appearing on the cybercrime scene, LockBit has been linked to almost 2,000 victims in the United States alone.

From the list of victims seen below, LockBit is clearly being used in a scatter-gun approach, with a wide variety of victims. This is not a series of planned, targeted attacks. Instead, it shows LockBit software is being used by a diverse range of criminals in a service model.

How we can protect ourselves

In recent years, ransomware as a service (RaaS for short) has become popular.

Just as organisations use software-as-a-service providers – such as licensing for office tools like Microsoft 365, or accounting software for payroll – malicious services are providing tools for cybercriminals.

Ransomware as a service enables an inexperienced criminal to deliver a ransomware campaign to multiple targets quickly and efficiently – often at minimal cost and usually on a profit-sharing basis.

The RaaS platform handles the malware management, data extraction, victim negotiation and payment handling, effectively outsourcing criminal activities.

The process is so well developed, such groups even provide guidelines on how to become an affiliate, and what benefits one will gain. With a 20% commission of the ransom being paid to LockBit, this system can generate significant revenue for the group – including the deposit of 1 Bitcoin (approximately A$58,000) required from new users.

While ransomware is a growing concern around the globe, good cybersecurity practices can help. Updating and patching our systems, good password and account management, network monitoring and reacting to unusual activity can all help to minimise the likelihood of any compromise – or at least limit its extent.

For now, whether or not to pay a ransom is a matter of preference and ethics for each organisation. But if we can make it more difficult to get in, criminal groups will simply shift to easier targets.

Read more: Australia is considering a ban on cyber ransom payments, but it could backfire. Here's another idea

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.