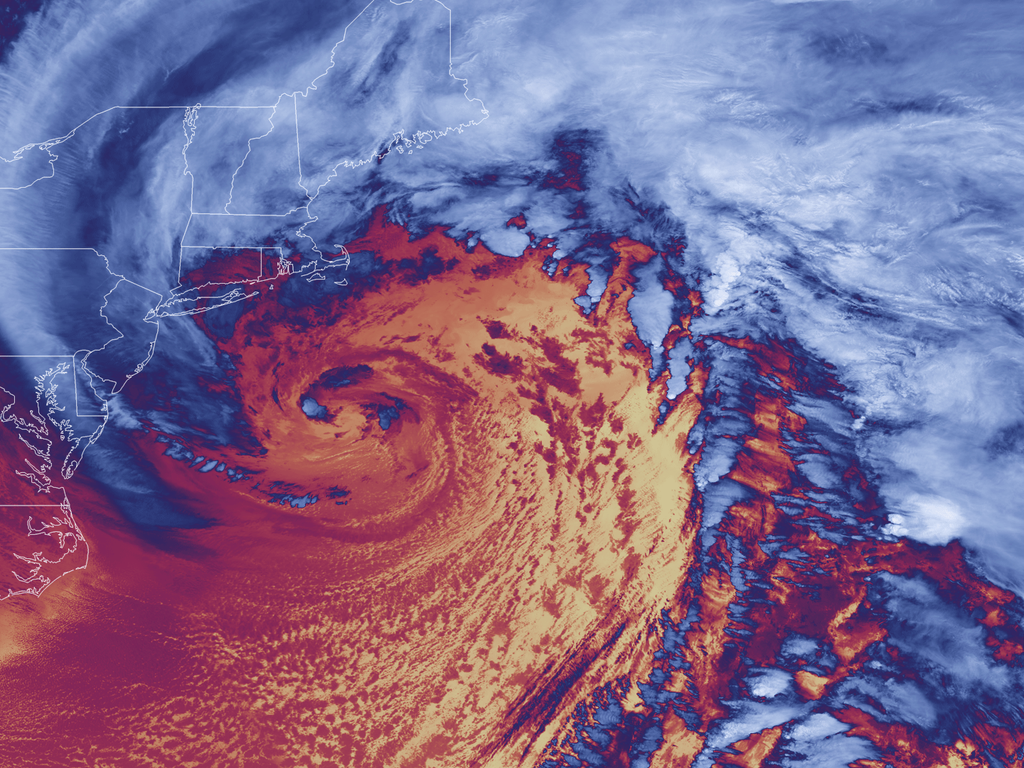

The US East Coast is bracing itself for a “bomb cyclone” that is on course to to barrel in from the mid-Atlantic on Friday, the nor’easter forecast to travel up the Eastern Seaboard and bring heavy snowfall along with the chill and potentially threatening wider disruption to power supplies and travel.

The National Weather Service has predicted the possibility of six to 12 inches of snow between Friday night and Saturday evening, with states from North Carolina to Massachusetts by way of New York and New Jersey braced for blizzard conditions.

However, the agency has tempered its warning somewhat by saying “there continues to be greater than usual forecast uncertainty with the track of this storm, and the axis of heaviest snowfall may shift in subsequent forecast updates.”

While the name sounds alarming, a bomb cyclone is relatively common in North America and the term, which was only coined in 1980, has been criticised by some meteorologists for being unhelpfully sensationalist and inspiring needless panic.

“Bombogenesis is the technical term. ‘Bomb cyclone’ is a shortened version of it, better for social media,” weather expert Ryan Maue has said.

“The actual impacts aren’t going to be a bomb at all. There’s nothing exploding or detonating.”

The occurrence, also known as explosive cyclogenesis, essentially amounts to a rapidly developing storm system, distinct from a tropical hurricane because it occurs over midlatitudes where fronts of warm and cold air meet and collide, rather than relying on the balmy ocean waters of late summer as a catalyst.

The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration says the process takes place when “a midlatitude cyclone rapidly intensifies, dropping at least 24 millibars over 24 hours”, citing the measurement used to record atmospheric pressure (the force being exerted by the weight of the air).

Like a conventional cyclone, a bomb cyclone is the product of a low pressure system, where the atmospheric pressure is lower at sea level than in the surrounding area.

Air drawn into the system from the Earth’s surface rotates in the same direction as the Earth when it rises, drawing in whirling winds at its base and creating the cyclone.

So long as the air continues to climb to the top faster than it can be replaced at the bottom, the pressure will continue to drop.

As with a hurricane, lower air pressure yields a stronger storm, resulting in high winds, heavy rains or blizzard conditions depending on the surrounding air temperature, with bomb cyclones most common in the US in late autumn and early spring when colder conditions are prevalent but not dominant.

“All bomb cyclones are not hurricanes,” climate scientist Daniel Swain of the University of California, Los Angeles, has told NBC. “But sometimes, they can take on characteristics that make them look an awful lot like hurricanes, with very strong winds, heavy precipitation and well-defined eye-like features in the middle.

“Fundamentally, the impacts of a bomb cyclone are not necessarily different from other strong storm systems, except that the fast strengthening is usually a signature of a very powerful storm system.”

It is not always clear what, if any, impacts the broader climate crisis has on a single weather event.

But, after a bomb cyclone struck an otherwise drought-ridden California and the Pacific Northwest last October, Dartmouth College professor Justin Malkin, a climate scientist, commented: “California is a sentinel state. It’s like a canary in a coal mine. The state is a crucial bellwether for society’s capacity to respond to these types of climate stresses happening today.”

Marty Ralph, director of the San Diego-based Center for Western Climate and Water Extremes, likewise said the “weather whiplash”, from drought and forest fires to sudden storms, experienced in the Golden State was “consistent with what climate projections indicated”.

Writing about whether global heating was playing a role in driving another bomb cyclone towards New England in January 2018, Annie Sneed of Scientific American said: “We would expect it to be playing some role, since climate change is fundamentally affecting the atmosphere and changing the base state in which storms arise.

“So potentially you would have more moisture available to this storm, just because the oceans are hotter because of global warming - and that could potentially increase the impacts of a storm like this.

“There’s also some question about whether global warming might be affecting the jet stream, which is an important trigger for this storm. [Climate change] may be making the jet stream have more meanders, more of these large loops - these kinks - that can drive these sorts of storms. It’s an active area of research, and there hasn’t been unanimous scientific agreement about how climate change is affecting these storms.”

Those concerned about staying safe on the East Coast this week are advised, as with any other strong storm forecast, to stock up on canned food, water, first aid supplies, a torch and spare batteries in case power supplies are knocked out.

“Pay attention to your local weather forecasters, but understand that the occurrence of a ‘bomb cyclone’ does not mean a storm will be particularly apocalyptic,” writes Rachel Feltman of Popular Science.

“You should still be safe and prepared, but that’s true of pretty much any winter storm.”