On York Boulevard in Los Angeles, a blurred black hole hangs on a dark wall, joined only by a pair of headphones playing looping echoes of its siblings colliding.

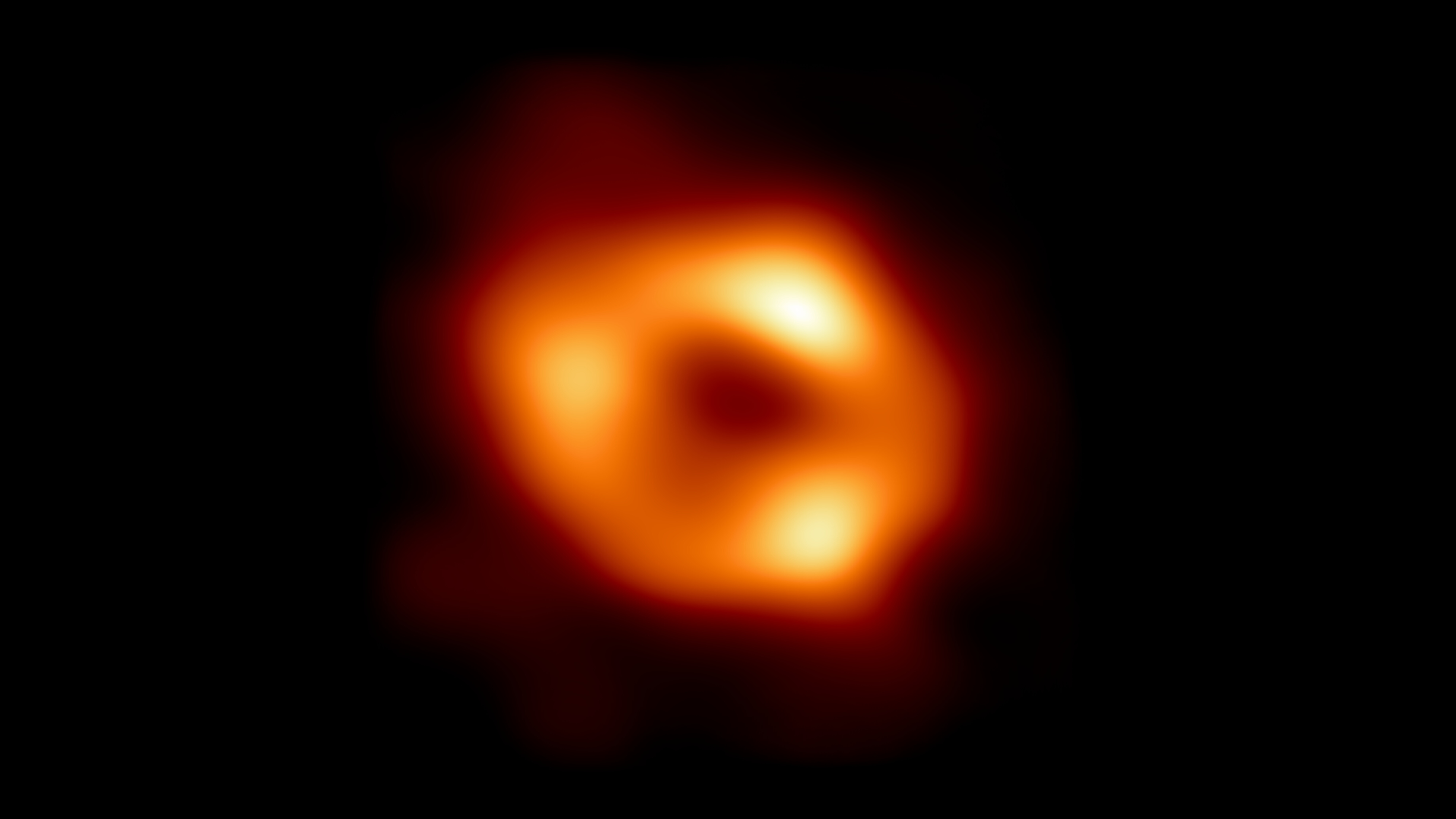

It's a familiar scene of our galaxy's supermassive central void, and certainly one that has flown far and wide over the years. I'd bet you've seen it. Journalists (including myself) have fawned over this image, affixing it to exhilarating news stories under titles like "First Image of Milky Way's Black Hole" or "Center of Our Galaxy Revealed." Universities have thrown it onto press releases about the Earth-spanning array of radio telescopes it owes itself to, and scientists have published it in heady studies while endearingly calling its subject just what it looks like: a fuzzy orange doughnut.

However, at the OXY ARTS gallery in Los Angeles, that abstruse portrait of Sagittarius A* looks a little different.

Isolated on its assigned wall, the 4.3-million-solar-mass black hole takes up space outside its usual astrophysical boundaries, both in the cosmos and in academia, to open itself up to artistic criticism and reflection. I have to admit, when I first saw it, my initial feeling was that it's curious to exhibit an unedited scientific image of the cosmos in an art gallery, and especially one that artists featured across the gallery didn't have a hand in creating. It seemed hollow, and even slightly ostentatious. But, after some time, I softened.

The intentionally empty area around Sgr A*'s frame seemed to actually punctuate its conceptual and visual weight in a way its typical online backdrop of search bars and Google Chrome tabs never has for me. The piece itself wasn't groundbreaking in my opinion, but the choice to put it up on a gallery wall at all might have been.

This made me start to wonder whether wavelengths of art and science tend to constructively or destructively interfere with one another, or whether they are really the same to begin with. For example, something that is extremely intrinsic to art, but not to science, is the idea of individuality. A true work of art is often considered irreplicable, but an ideal scientific conclusion relies on replicability to prove itself as a universal truth.

Though, on the other hand, one of the most well-known examples of someone who sang the song of art and science is Leonardo Da Vinci, whose masterpieces are specifically built on principles of anatomy, physics and mathematics. Would it be fair to ask which of the two disciplines came first for Da Vinci? Which was bubbling in his mind to begin with, reaching out to call for the other?

To be fair, I don't know whether I was wringing water from a stone with this thought. But even if I was, I think there's something interesting about that, too. French painter Marcel Duchamp once said in his 1957 talk about artistic criticism that "the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act."

This becomes more relevant when we think about why I was looking at this Sgr A* exhibit in the first place.

The spectators

For six days in September of last year, The Getty Museum's PST: Art and Science Collide event invited me to travel to about 30 galleries across Los Angeles and absorb the results of a challenge they gave various artists and art curators: to create exhibits that tiptoe the line separating art and science. In a sea of art journalists, I was one of the only science news representatives — if not the only one — meticulously searching canvases and sculptures for traces of contemporary discoveries and fundamental theories I'm so used to reading in black and white.

In other words, I arrived on this trip as an outsider.

Almost immediately, on day one, my status as a non-art-journalist became quite clear, and truthfully, enhanced the imposter syndrome I typically feel no matter the occasion. I didn't have the background knowledge of my peers when talking about up-and-coming artists, I didn't know the precise dynamics of art gallery bureaucracies and, more than once, I had to awkwardly ask one of my new friends how prolific the person I just talked to was. I simply didn't have the expertise necessary to comfortably judge art in an objective way, and in fact find the entire concept of artistic criticism a really complex one that's hard to penetrate. But what I did have was my knowledge of science.

Thus, I dutifully hunted for threads of equations in the art we saw — even if only to have something to hold on to. I treated it like a scientific conference, and this is where I started thinking about Duchamp's ideas.

Duchamp wondered about an elusive phenomenon in which a spectator reacts to a piece of work despite the artist technically having no part in that reaction. "This phenomenon is comparable to a transference from the artist to the spectator in the form of an esthetic osmosis taking place through the inert matter, such as pigment, piano or marble," he says, and I think the transference greatly depends on the mental pathways one is already predisposed to taking.

The concept reminds me of a scene from the TV show "Mad Men" in which someone buys an incredibly expensive piece of art but doesn't allow anyone in the workplace to see it. At last, a few characters manage to catch a glimpse, finding it to be no more than an annoyingly plain canvas with abstract red splotches. They immediately start reacting because they expected something more conventionally beautiful. But then, one of them, Ken, reflects that maybe reaction itself is the point. "When you look at it, you feel something," he states. Alas, without existing in the room, the artist managed to provoke emotion and spur a conversation about aesthetics.

With these scientific art exhibits, it seemed like the artwork inherently required both artistic and scientific spectators' reactions to bring the pieces toward their true potential.

The threads

One exhibit took place in Doug Aitken's industrial art studio, where strings of light ricocheted across the wall as a film played on the artist's projector, depicting evocative dancers in an Amazon factory, drivers in the countryside and a myriad other human experiences. It made me wonder whether quantum entanglement had anything to do with the piece, seeing as photons are quantum particles and entanglement involves these particles being connected despite existing in separate locations. It's even possible if the particles are on opposite sides of the universe, like Amazon workers in delivery trucks and billionaires on private jets.

However, someone else I met at the exhibition, who writes about dance, wasn't thinking about quantum mechanics. He pointed out the intricacies of the dancers' movements, and others across the room seemed to be paying close attention to Aitken's musical decisions and film direction.

At the Hammer Museum, walking into a small veiled room brought you to a large glass box within which live bees build honeycomb patterns on top of sculptures that coax those patterns into works of art. I and three others watched as a bee flew to the bottom of the container and carried one of its dead brethren to the top, where there is a tunnel to the outside world.

In another room of this museum, a dynamic black hole exists inside a space that comes with a warning about epilepsy. We don't know what black holes look like to the unaided eye, but I started pondering out loud whether they'd need an epilepsy warning for those who can circumvent getting stretched into noodle-like strips when faced with the void's gravitational pull — to the horror of a writer I met who was trying to capture the exhibit's striking colors on his phone because those colors fluctuated in peculiar ways on his mobile camera.

Nearby, you could sit on the floor and listen to the simulated sounds of the wilderness, while watching a video of the real wilderness, in front of a simulated pond with simulated ripples. I stayed there for a while, reminiscing about how this might be a window into our future once unchecked climate change ravages our world. Artwork at the SCI-ARC gallery, under the title "Views of Planet City" uses real satellite images and futuristic video game formats to imagine a hypothetical world in which humanity lives in a single city to allow the rest of the planet to heal. This brought me to tears in a way detached news about record temperatures didn't, and I noticed a few others having a similar reaction.

At the Brand Library and Art Museum, stalks of grass connected to mechanical blocks on the ground moved according to Martian wind patterns recorded by NASA's Perseverance rover on Mars. The movements were choppy not because the wind is jagged on Mars but because there are gaps in our data represented by gaps in the sway of the grass. Outside, a wall was decorated with bright yellow tape in a chevron pattern, tape that NASA uses to wrap instruments that blast off to locales far beyond Earth. On another wall, there was a microchip containing millions of people's names.

It has since been sent on a journey to Jupiter's moon Europa.

In his talk, Duchamp considered the two poles of the creation of art to be "the artist on one hand, and on the other the spectator who later becomes the posterity," giving essentially equal weight to both the creator and the one who witnesses the creation and carves its legacy.

Seeing or feeling artwork can be thought of as part of the artwork itself, in a sense; this becomes complex when considering how many different people, from different generations and with different perspectives, will act as spectators.

Scientific art managed to offer images to meanings I've conceptually considered for a long time, but I deeply wished I could see these pieces from the eyes of the art world to know how science might have enhanced, diminished or laterally woven into their experience. However, the individuality of art is unfortunately mirrored in the individuality of the creative act.

I especially felt this while standing under Olafur Eliasson's silver towers and peering upward. It was more mesmerizing than I can explain; it made it seem like light and mirrors are all you need to find a world in which physical infinity is within your grasp.

Still, I knew that was just the science journalist in me speaking.

This trip was funded by The Getty Museum as part of the PST: Art and Science Collide event.