Until the mid-19th century in Britain, watching someone die was considered a form of entertainment. Indeed, this shared experience shaped the landscape of London and bound the city together.

Entitled Executions, the current exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands tells the stories of tens of thousands of Londoners executed in public spaces across the city over almost 700 years, from 1196 to 1868 – the official recorded dates of its first and last public execution.

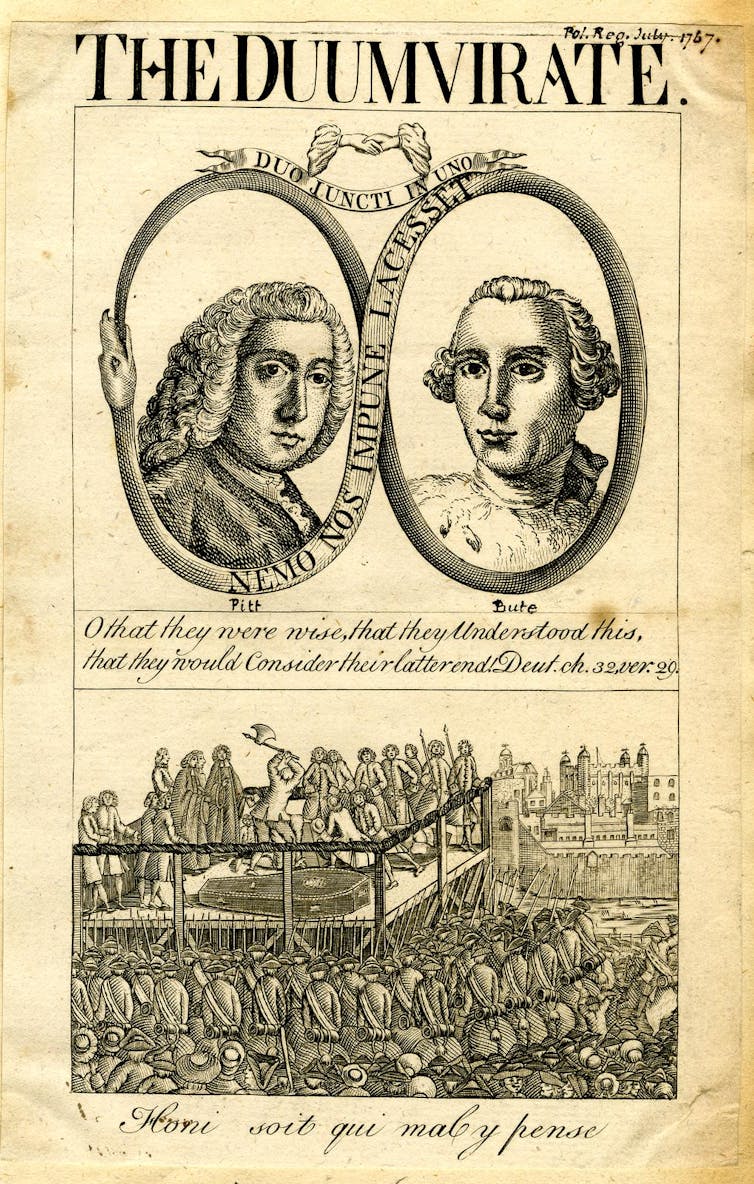

From gibbet cages erected on the main streets along the Thames, to pillories displayed for all to see at Charing Cross, and gallows at Tyburn (what is now Marble Arch) and Tower Bridge, public executions were a ritual which served several purposes. Learning about this history can offer insight into our contemporary appetite for – and apathy towards – the suffering of others.

Material expressions of state power

Executing someone in public and leaving corpses and other decaying body parts on display for several days (or years, in the case of gibbet cages) worked as a deterrent to crime and rebellion. The gruesome sight and the smell shaped collective memory and were a reminder that nobody could escape the dire consequences of crime. The exhibition shows that no one was spared – from the common man to public figures of the time and, indeed, the King.

In his 1975 book Discipline and Punish, French philosopher Michel Foucault explains that public execution was not just about the “theatre of punishment”. It was also about the material expression of state power – a ceremony through which the hold that the state, the crown and the church exercised over the life and death of citizens was made clear.

Different typologies of crime called for different methods of execution. By the end of the 18th century, in England there were 220 offences – from treason to pick-pocketing – that were punishable by death. This ruthless penal system became known as the “bloody code”.

These executions could be attended by up to 50,000 spectators, bringing significant economic gain. Hawkers sold fruit, pies and beverages to the public queuing for hours at the gallows. Window views over the site of the execution were rented to those spectators who could afford them. Print shops distributed “execution broadsides” throughout the country, reporting the last dying speeches of the condemned and reflecting, often in satirical terms, on the nature of their crimes.

In 1722, printer Thomas Gent wrote that, as he was printing the dying speech of Christopher Layer, who had been hanged for treason, he was besieged by hawkers anxious for the publication and was unable to step outside his office until he had finished.

Public gratification

Public executions were not just about the sentencing of criminals. They were viewed as events that lasted several days where the hangman, the condemned, the priest and the governor were actors playing roles in a bigger collective spectacle – and where audience gratification was as important an element as the punishment itself.

In 1783, English writer Samuel Johnson was asked where he stood on the subject of public hanging, and whether he would favour the alternative of executing criminals right after the sentence and without public announcement. He did not, replying: “The old method was most satisfactory to all parties; the public was gratified by the procession, the criminal supported by it. Why is all this to be swept away?”

Less than a century later in 1849, however, Charles Dickens witnessed the hanging of Marie and Frederick Manning, a Swiss maid and her publican husband who were condemned for the murder of Irish customs officer Patrick O'Connor. The letter Dickens subsequently wrote to The Times was lamentful:

I believe that a sight so inconceivably awful as the wickedness and levity of the immense crowd collected at that execution this morning could be imagined by no man, and could be presented in no heathen land under the sun. The horrors of the gibbet and of the crime which brought the wretched murderers to it faded in my mind before the atrocious bearing, looks, and language of the assembled spectators.

We know from literature, poetry and also science that the line between repulsion and attraction, horror and thrill, sublime and grotesque is fine. What sets the spectacle of public executions apart from these configurations is the staged, yet real, sensationalisation of an authentic tragedy.

The commodification of pain

Nowadays, images of death and suffering are routine in popular culture. In the age of tele-trauma, pain has been commodified. The suffering individual is lost and repackaged into a fictional other for our consumption.

French philosopher Jean Baudrillard’s work shows that consumption has nothing to do with gratifying our needs. Rather, it is the contemporary way in which we relate to one another and to society at large. In processing information from the media, we transform objects (reality) into signs (virtuality) to create alternative value-systems. These form a falsified reproduction of reality which alters public consciousness.

In other words, the media articulation of violent images and language produces specific meaning about the suffering of others. It shapes up specific ways in which we – the audience – engage with those distant and mediated vulnerabilities. This produces a shift in our response to pain and suffering. We move from empathy to apathy.

In the mid-19th century, Dickens was already noting how the spectacle of public execution triggered a collective disconnect from the suffering of others. In his letter to the Times he wrote:

When the day dawned, thieves, low prostitutes, ruffians, and vagabonds of every kind flocked on to the ground, with every variety of offensive and foul behaviour. There was no more emotion, no more pity, no more thought that two immortal souls had gone to judgement.

Today we continue to both demonise and crave the vulnerability of others. The difference is that we no longer do it collectively in the public square, but intimately in our homes. It is an exercise which Baudrillard describes, in his 2000 book Screened Out, as a “great laundering”. By falsely identifying with distant victims of pain from our position of safety, we are able to condone our indifference and overwrite a more edifying, self-absolving story.

Caterina Nirta ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.