Thames Water has warned the government that it faces bankruptcy if it is not allowed to raise bills by more than agreed with regulator Ofwat. The UK’s biggest water company will put it’s prices up by 35 per cent over the next five years, down from the 53 per cent that was requested.

Bosses have argued that the additional funding is needed to pay for new infrastructure investments over the next five years, but Ofwat has declined to change its decision. Thames Water now has until 18 February to decide whether to appeal to the Competition and Markets Authority.

Representatives for the water supplier maintain that the funding settlement will not allow the company to restructure its debts, increasing the chance of bankruptcy. Thames Water is trying to secure £3bn in emergency funding to protect against imminent collapse, a plan which London’s High Court will decide on in Febrary. The company is also looking to find £3.25bn in equity investments to 2030.

These financial lifelines are preferred by the company’s creditors, but campaigners say the cost of the emergency funding would be passed on to Thames Water customers.

But if Thames Water is unable to increase its bills any higher and also fails to secure emergency funding, the possiblity of bankruptcy will become even more real, forcing the government to step in.

What happens if Thames Water goes bankrupt?

If Thames Water goes bankrupt, the government would be forced to carry out some form of nationalisation. Ministers have reportedly already begun looking for potential special administrators to take over the beleagured water company.

This would put it into a special administration regime, taking in to temporary government ownership to ensure that its essential water service continues.

However, the move could also force the government to take on Thames Water’s £16bn debt pile. This would be a major blow for the Treasury, especially to come at a time when economic growth remains inconsistent.

Whitehall officials have begun drawing up the plans under the codename ‘Project Timber,’ it was revealed in April last year. This would see Thames Water run by the government as an arms-length body, giving it far greater control of day-to-day operations. Meanwhile, current lenders would lose up to 40 per cent of their money.

Ministers would be faced with deciding whether the company would remain a public asset or become privatised again. The Labour government has said it has no intention to nationalise the water industry – citing a cost of £90bn and need to deal with issues quickly.

However, ministers have moved towards nationalisation in other industries. Rail nationalisation is expected to finish in 2027, while work on publicly-owned GB Energy continues. Projects like these may well pave the way for other similar endeavours in the future.

When did the problems with Thames Water start?

Some would argue Thames Water’s problems go back to the 1980s, when it was privatised alongside all the other water companies.

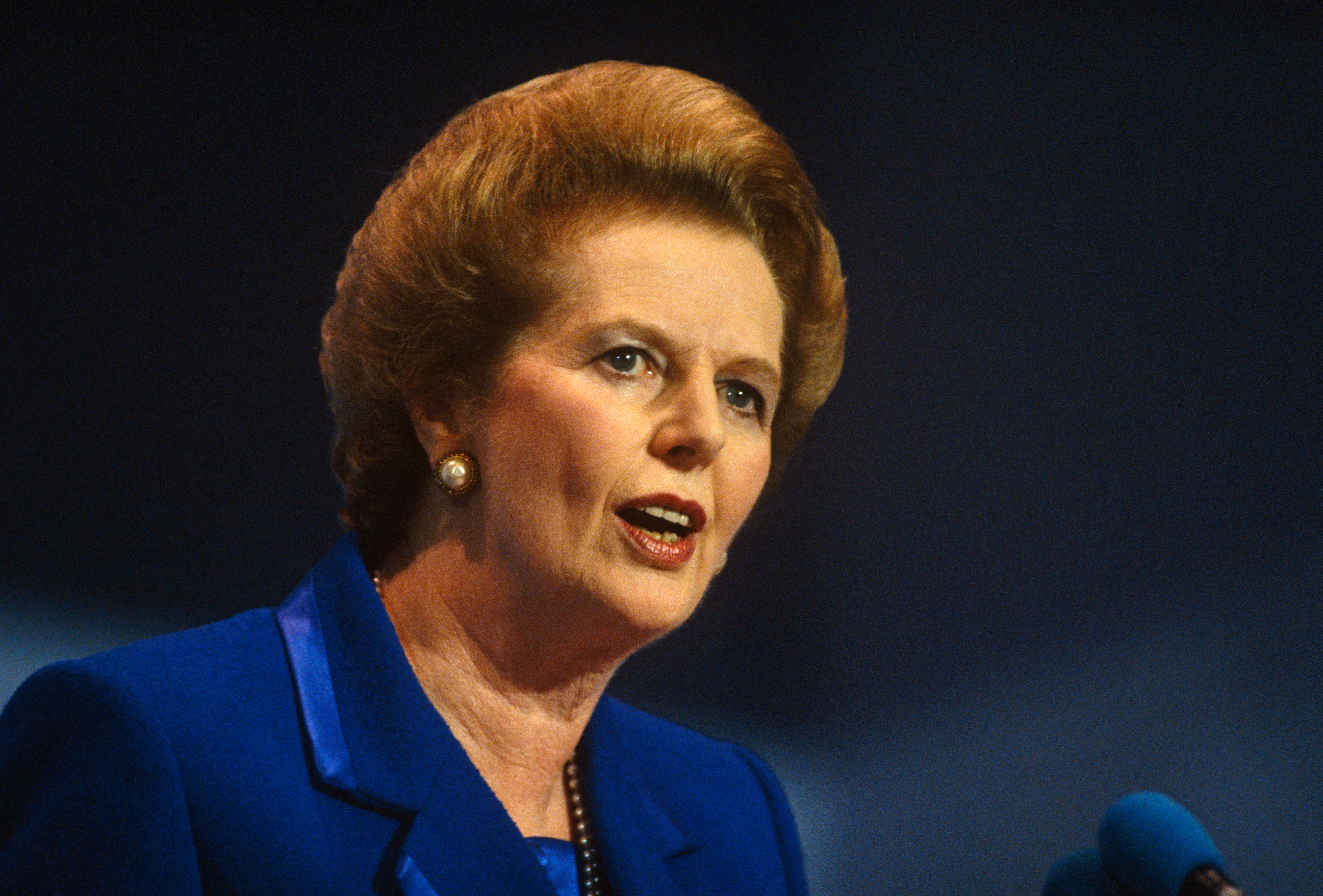

In 1989, Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government sold off England and Wales’ ten regional water companies to the newly created Water and Sewerage Companies (WSCs) for £7.6bn.

The move was unprecedented, and was the second attempt after an unsuccessful first run in 1984, when there was massive outcry against Ms Thatcher’s plans. However, bolstered by her 1987 general election win, the plans were pushed through.

The move came after Ms Thatcher imposed tight restrictions on the water companies which prevented them from being allowed to borrow for capital projects. This then became part of her government’s justification for selling them to private owners.

Ms Thatcher once said the Conservatives were against nationalisation because “we believe that economic progress comes from the inventiveness, ability, determination and the pioneering spirit of extraordinary men and women.”

“If they cannot exercise that spirit here, they will go away to another free enterprise country which will then make more economic progress than we do.”

In 2025, England and Wales remain two of the few countries in the world to have fully privatised water services.

According to pro-nationalisation campaign group We Own It, water bills in England and Wales have gone up by 40 per cent in real terms since nationalisation, while the average salary of a water service CEO is £1.7m a year.

Thames Water in the 21st century

Since 2001, Thames Water has had three owners. It was acquired by German utility company RWE in 2001 and sold to Macquarie in 2006 following criticism over leakage targets.

Macquarie’s ownership lasted for 11 years, until 2017. During these years, Thames Water acquired the highest debt in the sector, as owners pursued severe underfunding and cost-cutting measures alongside massive shareholder dividend payouts.

Under Macquarie, debts almost tripled from £3.2bn to £10.5bn, as shareholders were paid £2.8bn.

The company is now owned by several major shareholders, including several pension funds. The largest ownership shares are OMERS (32 per cent), a Canadian public pension fund, and the UK’s Universities Superannuation Scheme (20 per cent).

The path to financial recovery for Thames Water has been difficult, with former CEO Sarah Bentley stepping down suddenly in June 2023 after three years in the role. She was replaced by former British Gas executive Chris Weston the following December, who will receive a pay package of reportedly up to £2.3m a year with bonuses.

In December, Thames Water was fined £18 million by Ofwat for “unjustified” dividend payments which it say broke shareholder payment rules. The regulator also clawed back £131 million worth of dividends.

Now in 2025, the company finds itself one step closer to bankruptcy – its future looking less certain than ever.