Bear Stearns played a pivotal role in the Financial Crisis of 2007–2008: It was the first Wall Street institution to collapse and be “bailed out” by the U.S. government due to its risky investment practices involving subprime mortgages.

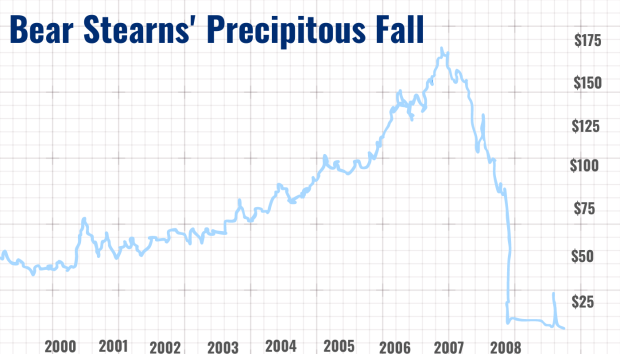

In 2008, a mind-boggling amount of leverage on Bear Stearns’ balance sheets left it with no margin for error, which meant even a small drop in the value of its assets would wipe it out permanently. And so, what went up quickly came down.

What Did Bear Stearns Do?

Bear Stearns was actually the smallest of the top five investment banks on Wall Street, alongside the ranks of Goldman Sachs, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, and Morgan Stanley. Founded on May 1, 1923, by Joseph Ainslie Bear, Robert B. Stearns, and Harold C. Mayer, Bear Stearns had survived the Great Depression, the stock market crash of 1987, and the September 11 terrorist attacks, growing from just three employees to more than 15,000 by 2007 with trading desks around the globe. It even made Fortune’s 2007 list of “most admired companies.”

Bear Stearns minted profits in the early 2000s from its aggressive stakes in collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), which were securities that contained thousands of adjustable-rate subprime mortgages. At the street level, these home loans were sold by predatory lenders who often targeted low-income and minority homebuyers with low credit scores. Poorly explained and complex in nature, the terms of subprime loans started out inexpensively—some even allowed the borrower to buy a house with zero down payment. But after a short, introductory period, subprime mortgages shot up by several hundred dollars a month, if not more.

The U.S. housing sector was simply unstoppable back then: Home prices had doubled between 1998 and 2006, and housing-related industries accounted for nearly half of all new jobs. But as more and more people signed on to mortgages they actually couldn’t afford, a bubble formed in the housing market. Even then-Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan voiced his concerns about the housing bubble’s “froth.”

“The apparent froth in housing markets may have spilled over into mortgage markets. The dramatic increase in the prevalence of interest-only loans, as well as the introduction of other relatively exotic forms of adjustable-rate mortgages, are developments of particular concern. To be sure, these financing vehicles have their appropriate uses. But to the extent that some households may be employing these instruments to purchase a home that would otherwise be unaffordable, their use is beginning to add to the pressures in the marketplace.”

—Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, U.S. Congressional Testimony (June 9, 2005)

How Was Bear Stearns Connected to the Mortgage Industry?

As soon as homeowners had signed their papers and picked up their keys, firms like Bear Stearns were bundling these mortgages with thousands of others, transforming—or securitizing—them into liquid financial vehicles, like CDOs, that could be traded by institutional investors like hedge funds.

CDOs were categorized by slices, or tranches, according to variables like their underlying home values or the credit score of the mortgage holders. Credit ratings agencies would assign grades to these tranches: AAA was the highest and safest rating—it was directed to Class A securities, which usually sported the lowest yield, along the lines of Treasury securities, while lower-rated tranches, such as Class B and Class C securities, contained subprime mortgages. These boasted much higher yields to offset their increased risks.

These financial vehicles soon grew more and more complex. CDOs were spun out from other CDOs; when firms ran out of products, they actually created synthetic CDOs, which were made entirely of derivatives. The Securities Industries and Financial Markets Association reported that by the end of 2006, $316.4 billion of mortgage-related CDOs had been issued, an astonishing 77% increase over 2005.

Thirsting for even more profits, Bear Stearns took even greater risks. It acquired three subprime originators and flexed a stronghold over the mortgage business, managing nearly every aspect of the mortgage process, from originating and securitizing mortgages to bundling CDOs into other securities before trading them with other investment banks.

At a time when other firms were exiting the subprime sphere, Bear Stearns actually increased its leverage. According to a report by the Congressional Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, by 2006, Bear Stearns had just $11.8 billion in equity and yet had assumed $383.6 billion in liabilities. It was borrowing as much as $70 billion in overnight markets.

If only Bear Stearns had stopped to listen to the fizz as the housing bubble popped …

Between 2004 and 2006, the Federal Reserve implemented a series of 17 interest rate hikes, from 1.0% to 5.25%, which effectively exposed the holes in subprime lending since so many of these mortgages were tied to prevailing interest rates. As rates shot up, millions of homeowners became unable to make their monthly payments and defaulted on their loans. CDOs depended on the cash flows generated by their underlying assets, and so when homeowners missed their mortgage payments, these securitized assets literally became worthless.

The bottom fell out for Bear Stearns.

Canva

When Did Bear Stearns Collapse?

Bear Stearns had been in trouble as early as June 2007, when two of its hedge funds imploded, the Bear Stearns High-Grade Structured Credit Fund and the Bear Stearns High-Grade Structured Credit Enhanced Leveraged Fund. They were part of Bear Stearns’ asset-management business, which received little oversight; both funds were heavily invested in CDOs.

- Bear Stearns’ High-Grade Structured Credit Fund had assets of $8.6 billion, but only $900 million was investments. The other $7.7 billion was borrowed money. It also had a leverage ratio of 10:1.

- Bear Stearns’ High-Grade Structured Credit Enhanced Leveraged Fund was described by its manager, Ralph Cioffi, as a “levered version of the High-Grade fund.” It contained $900 million in investments and $8.5 billion in borrowed money and was advertised to investors as being “complex” and therefore “undervalued.”

As much as 60% of the High-Grade Fund’s collateral was made up of CDOs, and as the subprime crisis intensified, it began to hemorrhage, losing 4% in the final quarter of 2006, then 8% in January 2007, and 25% in February 2007. Cioffi and his co-manager, Matt Tannin, tried to raise capital through investor conference calls; when that didn’t work, they tried to offload some of the now-toxic CDOs, but this also failed.

In April 2007, Cioffi told investors the Enhanced Leverage Fund had declined 19%. Fearing a run, redemptions were frozen. As the subprime market continued to deteriorate, Bear Stearns attempted an internal bailout of $3.2 billion, but it wasn’t enough. By the summer, the High-Grade Fund had lost 91% of its value, while the Enhanced Leverage Fund was completely defunct. On July 31, 2007, both funds filed for bankruptcy. Cioffi and Tannin would face criminal fraud charges for misleading investors, although they would both later be acquitted.

Bear Stearns posted a 61% decline in net profits in its Q3 2007 earnings statement, with income of $166.1 million compared to $432.2 million in the same quarter of 2006. In November 2007, Standard & Poor’s downgraded Bear Stearns’ mortgage-backed securities from AA to A; other downgrades would follow. In the fourth quarter, the company reported its first-ever loss of $327 million.

By March 11, 2008, when Moody’s downgraded Bear Stearns’ mortgage-backed securities from B to C, panicked hedge fund customers sparked a bank run, withdrawing their investments en masse and depleting Bear Stearns’ liquidity from $18 billion on March 10 to just $2 billion on March 13.

Bear Stearns was bankrupt.

Who Bought Bear Stearns?

On March 13, the firm notified the Federal Reserve that it did not have enough funding to cover its obligations and could not find a source of financing in the private sector. Bear Stearns’ CEO, Alan Schwartz, had called Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JPMorgan Chase (JPM), requesting a $30 billion credit line, but JPM refused unless they received government backing.

On March 14, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York provided Bear Stearns with a $12.9 billion credit line through JPMorgan Chase, which would cover its liquidity needs for the next 28 days.

That weekend, the Fed facilitated a sale of Bear Stearns to JPMorgan Chase and created a limited liability company, Maiden Lane LLC, to purchase its illiquid assets. The Fed would buy $30 billion of these assets as well as provide an additional $29 billion loan.

JPM’s acquisition of Bear Stearns was initially arranged for just $2 per share. Minutes of the board meeting discussing the sale revealed that initially, JPM had considered $4 per share but lowered its bid, blaming the government, stating “The Fed and the Treasury Department would not support a transaction where Bear Stearns’ equity holders received any significant consideration because of the ‘moral hazard’ of the federal government using taxpayer money to ‘bailout’ Bear Stearns’ stockholders.”

Then Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke said the decision was the toughest of the financial crisis.

“Given the exceptional pressures on the global economy and financial system, the damage caused by a default by Bear Stearns could have been severe and extremely difficult to contain,” Bernanke told the Senate Banking Committee.

In other words, Bear Stearns received a lifeline because it was “too big to fail.” Its fallout would have been a systemic risk to the financial system.

All that being said, on March 24, Bear Stearns’ shareholders announced a class action lawsuit challenging the sale. A new agreement, raising the price to $10 per share, was reached later that day.

Dimon was said to have been “apoplectic” over the deal. Speaking later to the Council on Foreign Relations, Dimon said that JPM did the government “a favor” by taking on Bear Stearns, adding that they had “asked them” to do it.

“I think the government should think twice before they punish business every single time things go wrong.”

—JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon, 2012

Is Bear Stearns Still in Business?

After Bear Stearns was acquired by JPMorgan Chase, only 5,000 of Bear Stearns’ employees retained work with the company. Those who lost their jobs received severance payouts that included three weeks of pay for each year they worked with the company plus an automatic eight weeks, a one-time grant of JPM stock, as well as their 2007 bonuses.

Bear Stearns' website, www.bear.com has since been redirected to JP Morgan Chase.