More than 50 years ago, the late Father David Bauer pointed out that studies and reports on problems in Canadian ice hockey have had a “characteristic ineffectiveness.”

This was because they have “come from outside the structure of organized hockey and they have been isolated efforts.” Those inside the game tend to get “impatient with well-meaning outsiders” who often “oversimplify” the issues at hand.

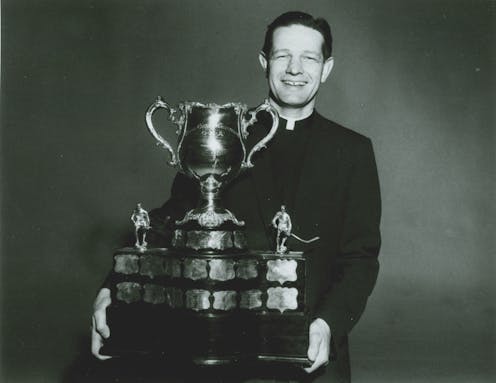

Bauer was born just over 100 years ago. Some have called him the moral conscience of hockey; others saw him as the father of Canada’s hockey team. There are arenas in Vancouver and Calgary named after him, while a major street in downtown Waterloo, Ont., is dedicated to him.

Bauer’s 1973 depiction of Canadian hockey as “complex” and constantly in “rapid transition” feels remarkably similar to the state of the game today.

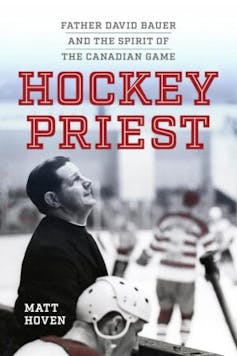

As detailed in my recent book, Hockey Priest: Father David Bauer and the Spirit of the Canadian Game, Bauer brought change to the sport through his work as a coach, manager and philosopher.

Today, Canadian hockey faces a number of challenges, from new eligibility rules in junior and college hockey to calls for greater inclusion across the sport and alleged cover-ups of abuse, to a decline in youth participation. With questions swirling about the state of hockey in Canada, it is valuable to hear from a central historical figure whose insights can help reshape its future.

Bauer and the national team

Bauer played junior hockey at St. Michael’s College-School in Toronto and went on to win a Memorial Cup championship as a player and later as a coach. Meanwhile, he became a priest of the Basilian Fathers and notably established Canada’s national hockey team.

It was the first time Canada was represented internationally with a hockey team composed of players from across the nation. The national team played at three Winter Olympics and several international tournaments under Bauer’s leadership.

He was also the longest-serving original member of the Hockey Canada Corporation board from 1969 to 1988. He was among the first recipients of the Order of Canada and was posthumously named to the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1989.

Although he was a celebrated hockey personality, Bauer had serious misgivings about the way hockey was run and organized. He argued about the educational needs of young men in junior hockey with Toronto Maple Leafs owner Conn Smythe. He advised top junior players, like Dave Keon and Gerry Cheevers, in contract negotiations, leading Maple Leafs general manager Punch Imlach to famously retort: “That man should no more be a priest than me.”

Bauer set before the Canadian public a different vision of the game in contrast to overly commercialized hockey that was simply viewed as entertainment. He saw no need for fist-fighting in the game, especially goonism.

He promoted a game of speed and checking without physical intimidation, and believed the game ought to be more of an art form than a crash-and-bang event on ice. He commented that “too much board-thumping hockey” became popular in the post-Second World War period and was pleased to see the rise of puck possession play.

He learned from both his family and the Basilian sporting tradition that hockey is also an educational experience. He argued that sport properly directed could assist young people and strengthen communities. To a reporter, he added a not-so-subtle challenge to the status quo in Canadian hockey: “If we say economics are the only thing that counts, which the NHL keeps saying, we’re in serious trouble.”

The national team and Bauer were early advocates for coaching clinics that could improve the level of play in Canada. This was something that later national team coaches actively promoted into the 1990s. Bauer’s motto — “use technique, but let the spirit prevail” — affirmed the importance of better skills, tactics and conditioning along with promoting the spirit and personality of the individual player.

Solutions for Canadian hockey today

Bauer was uneasy about any model that focused on skill development and neglected the development of the total person. His overarching goal for youth playing hockey was to instill them with what he saw as the virtues of the game. If a young player could improve “as a person through virtues of hockey — courage, judgment, prudence, fortitude, teamwork and fair play,” he said, they would improve as a hockey player.

This perspective stood in contrast to the priorities of those who only cared about the final score and the bottom line.

To “capture the fleeting idealism of our youth,” Bauer asked hockey coaches to learn from the young people playing the game, as if to reawaken the aspirations of their own childhood by supporting the dreams of youth.

Bauer was not a dreamer, however. For him, economics should not be the sole standard by which to measure the sport. He also was critical of an overly violent form of the game. He questioned scientific and technological advancements that did not consider human values. “Know how” is meaningless by itself: “It is a means without an end,” he said.

He demanded that coaches understand the values and spirit they wished to promote in hockey. His was an athlete-centred approach. He wanted the game to “be motivated by a habitual vision of greatness, to help each person we meet have a positive self-image, inner discipline, a sense of loyalty, and responsibility to themselves and society.”

This vision of hockey is one that promotes unity of the body and spirit, where everyone in hockey should care about players’ physical development and the growth of their personality and inner life.

As stated to a reporter prior to the 1988 Calgary Winter Olympics, he believed that “in a small way, hockey can improve the world.” Bauer’s way was to recognize the limitations of sport and put it in its proper perspective: to specify that hockey is not everything and, at the same time, that it could make a real contribution to the lives of Canadians.

Hockey needs to state its values and organize itself accordingly. By having a Bauer-like approach to hockey, sporting bodies, coaches and players can reckon with the challenges facing the game.

“Hockey is not the most important thing around…[but] it might be that it is the most Canadian thing,” he said. This statement reflects Bauer’s attempt to put hockey into its proper perspective: a Canadian sporting activity that in its own way can improve people’s lives.

Matt Hoven does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.