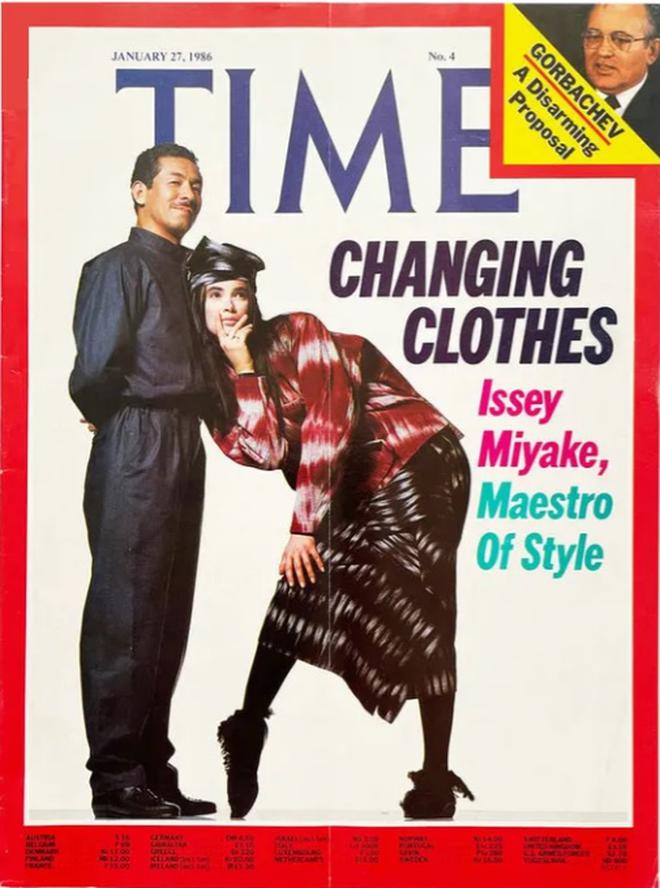

What do we lose when a designer like Issey Miyake — with global impact on how the human form can determine the shape of clothes, the dance between engineering, technology and textile — is gathered to dust? What do social media “likes” and traction to Miyake’s obituaries suggest?

Younger Indian consumers may not instantly connect ubiquitous Issey Miyake perfumes with a Japanese mind first inspired by bridges named Ikiru (to live) and Shinu (to die). Whose East meets West fashion in the 70s, especially the ‘Paradise Lost’ collection of 1976 and since then, was not merely a predictable ascendance of Asian design to international acclaim. It was a one-of-a-kind “arrival”, even though Kenzo Yakada had been there before Miyake.

Will his departure then also leave a one-of-a-kind hole in imagination that can never be darned? Or does life, like the Japanese art of kintsugi (which uses gold and silver dust but fosters the idea that broken objects can be repaired and used again), offer hope? Most importantly, what does Miyake’s inspiration mean today for Indian fashion?

A long list of Indian designers, young and senior, use Japanese influences. Not just in apparently derivative pleated garments, kimono-shaped sari blouses, black and white colour grids or deconstructed silhouettes. But by experimenting, ingeniously, with avant garde ways of engineering, cutting, stitching and presenting fashion. Using manufacturing processes to minimise waste. Making anti-fit garments, using knits and weaves to celebrate “irregularities” in handwork and “imperfections” in finish. By reinventing ikat and shibori — both common artisanal practices between Japan and India — beyond existing vocabularies of traditional textiles.

Indian expression

Consider these. Mia Morikawa and Shani Himanshu’s ways of using local crafts, dyes, organic materials and farmer-spinner-designer dialogues for their label 11.11. Aneeth Arora’s sophisticated repairs of vintage textiles much like kintsugi art. Amit Aggarwal’s couture laboratory that works with discarded polymers and industrial waste. Gaurav Jai Gupta’s engineered handlooms. Or, Ahmedabad-based designer Anuj Sharma’s Button Masala concepts of adaptable, functional garments made without multiple tools or machines.

Some senior Indian designers have in fact given Asian design a wider lens with their work — Japanese perhaps in philosophy, Indian in expression. David Abraham and Rakesh Thakore with their globally recognised ikats for A&T; Thakore’s seminal black and white Andhra ikats, some of which he created for Issey Miyake Design Studio. Neeru Kumar’s handwoven tussars, khadis, ikats and kanthas — as home textiles or fashion — are on that list too. Kumar has been selling to the Japanese market for more than three decades. As do several others.

Miyake, however, beyond his brief collaboration with the Sarabhai Foundation of Ahmedabad, and the late Gira Sarabhai, and separately with designer Thakore — was creating a lasting era of “blends”. That became Japan’s language of fashion communication with the world. Technology with tactility. Utility with art. Freedom with form.

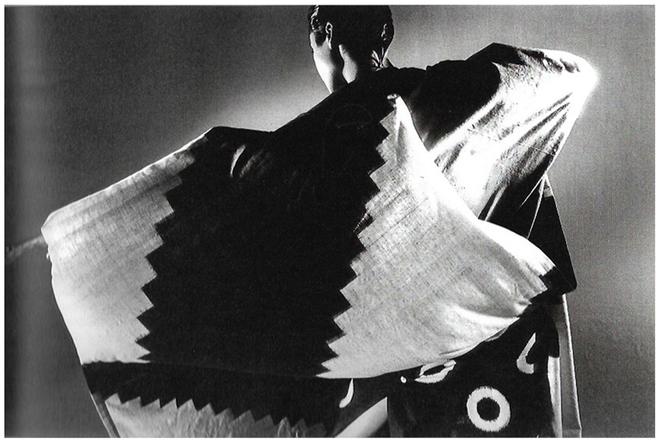

Miyake made fashion adaptable. He announced “poems in cloth and stone” after his graduation. The Pleats Please inventive phase saw clothes made in solid colours without buttons, zips or strings in heat-pressed, pre-pleated fabrics that would address everything from size to shape to folding, twisting, washing and crushing. Easy to perform, play, live and tire in. This was not Western fashion or Japanese street style that had surged after World War II, but a category of its own.

Curiously, today as Indian design propels to global attention, it too is a recognisable “category” on its known. Eastern in creative process, South Asian in craftsmanship without Japanese referencing, which underlines its distinction.

Japanese design is essentially minimalist, it eschews decoration and excess. Indian design is maximalist, and even when toned down, it responds to our cultural need for excess. Sabyasachi Mukherjee’s decadent jewels, Taj Mahal bags and embellished fare at Bergdorf Goodman, Rahul Mishra’s soaked-in-embroidery couture at Paris, and Manish Arora’s (until he stopped showing in 2019) chaotic, controversial idea of India. Everything is a riot. Of techniques, materials, influences and over-stacked colour.

We are a category. And we are not Japanese. Then why are we mourning Miyake?

Trends and tactics

Indians — consumers or designers — may admire Japanese simplicity. But let us appreciate Japanese design and Miyake in particular for the right reasons at least.

In order to maintain his brand in the shifting fashion world and to prolong the growth phase, Issey Miyake used a tactic unusual in the West.

Throughout his career, he financed his successive assistants… he dedicated himself to a futuristic line, A-POC (A Piece of Cloth), that gave him room to express his talent.” So wrote Didier Grumbach, global fashion voice and co-founder of Saint Laurent Rive Gauche, in his 2014 book History of International Fashion.

For Miyake, “unusual tactics” were mixed with following trends. That’s what he did with perfumes following French fashion houses in the 80s when couture was married to the lucrative industry of perfumes to survive financial ups and downs and stay in constant public recall. He tapped into a business instinct and launched the floral, spring-evoking perfume L’Eau d’Issey in 1992. Even as he emphasised, “I like the idea of a scent, but not of a fragrance,” thus marking a cultural difference from what was going on at houses such as Jean Patou, Balmain, Yves Saint Laurent, Chanel, Dior, Givenchy, and many others.

Textile to art

If the black turtleneck made notoriously famous by late Apple founder Steve Jobs was a Miyake creation, so was the never-before Bao Bao bag. Made from a mesh fabric and triangles of polyvinyl, it became a design school kit for creativity. He elevated textiles to sculptural art, making couture that could be worn like ready-to-wear.

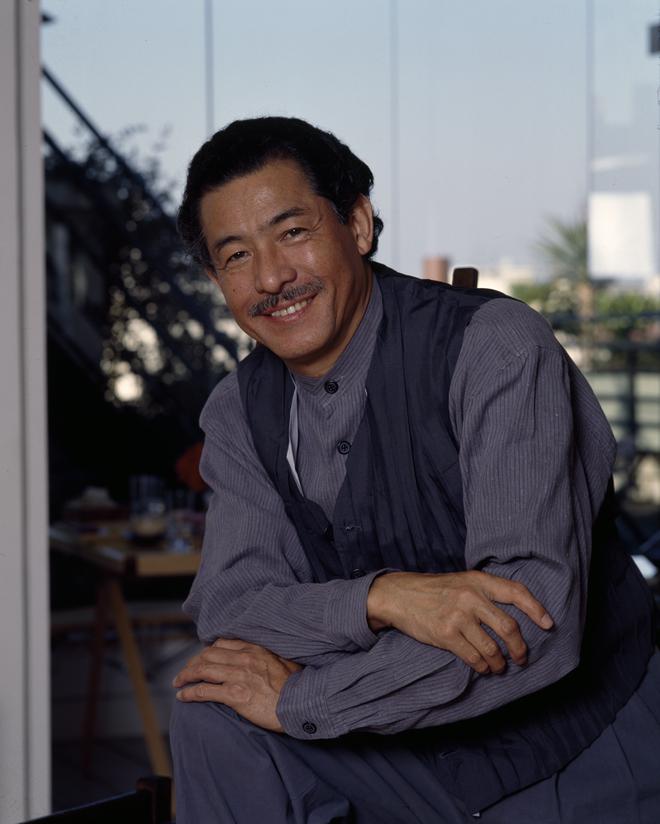

Through all of this, Miyake showed a way of doing business in a foreign country. Yet he remained “Japanese” at the peak of his career even when he lived and worked in Paris. Never sacrificing creativity for commerce, focused always on ‘Making Things’ as his 1998 Paris exhibition was called. In later years, he dedicated himself entirely to A-POC, developed initially with Dai Fujiwara.

Based on an engineering design, A-POC put the consumer in the centre. A-POC used a single thread fed into a computer-programmed, industrial weaving machine. In one process, the machine created elements of a complete outfit that rolled out as a single tube of fabric. It could be cut following demarcating lines with scissors. Once done, that tube of fabric could produce a dress, a pair of pants, a top or a hat.

This approach that mixed fashion, art and technology with cultural authenticity was Miyake’s ‘reason of being’ or ‘ikigai’.

‘Kazunaru’ (or Issey) means ‘one life’ as the book Where Did Issey Come From? by Kazuko Koike notes. A survivor of the 1945 Hiroshima bombing, how Miyake made “peace” with cloth is surely one way to memorialise him. The kind of peace Indian design could do with.

The writer is editor-in-chief of ‘The Voice of Fashion’.