When Chinese student Ding Xueliang was studying in the US city of Boston in the late 1980s, one of the biggest lessons he learned occurred outside the classroom.

Ding crossed paths with a number of other Chinese students who had arrived in the United States fresh from taking part in protests that had gripped several cities in eastern China, including Shanghai, for a month from December 1986.

The demonstrators took to the streets in frustration at corruption, eventually expanding their demands to political reforms.

But Ding said that when he asked the other students what prompted the protests, he was surprised by the answers.

In the few years that he had been studying abroad, the economic structure had changed dramatically, and people in the emerging private sector were earning more than those with fixed incomes, irrespective of their contribution to society.

The people who designed missiles now made less than those who sold eggs, they told him.

“Soon, [then paramount leader] Deng Xiaoping said the goal of socialism was common prosperity, and making a small number of people rich first would help to better achieve the goal,” said Ding, now a member of the academic committee of the Hong Kong-based BoYuan Foundation.

“But making a small number of people rich first was supposed to be transitional, which would be later adjusted by policies and laws to achieve common prosperity.”

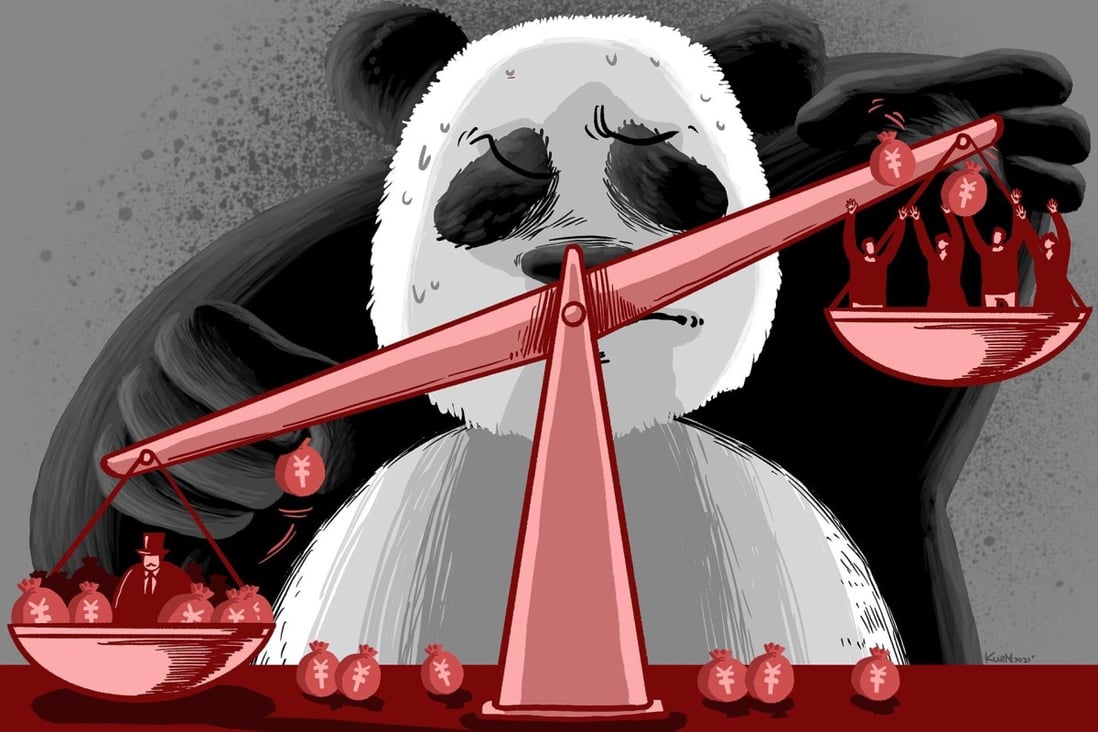

Decades later, there are signs that the transition period could be ending and the focus of the leadership now is a more equitable distribution of income, with President Xi Jinping reviving the goal of common prosperity.

The idea has been an underlying theme in Xi’s speeches over the years and builds on the work of his predecessors, observers say.

Why the backbone of China’s economic machine is falling apart

Ding said former president Hu Jintao and former premier Wen Jiabao sought to address the disparity between the rich eastern and impoverished western regions, as well as the disparity between the agricultural and industrial sectors.

But the most recent – and clearest – sign of the renewed focus came on Tuesday after a meeting of China’s top economic decision-makers.

According to a statement released by the Communist Party’s Central Committee for Financial and Economic Affairs, Xi said now was the time to give the less well off a fairer deal.

“We can allow some people to get rich first and then guide and help others to get rich together … We can support wealthy entrepreneurs who work hard, operate legally, and have taken risks to start businesses … but we must also do our best to establish a ‘scientific’ public policy system that allows for fairer income distribution,” the statement quoted Xi as saying.

China’s income inequality could expand in 2020 as outbreak rattles world’s No 2 economy

As part of that process, the government would alter the tax and social security regimes and make a range of fiscal transfers to allow for greater upwards mobility and better access to education.

The decades of economic liberalisation have delivered tremendous wealth, creating a middle class of 340 million people earning between US$15,000 and US$75,000 per year. That number is projected to reach 500 million by 2025.

China also had 5.28 million “millionaires”, with household wealth above US$1 million, by the end of last year. In 2020, the wealthiest 1 per cent of Chinese people held 30.6 per cent of the country’s wealth, up from 20.9 per cent two decades ago, according to a Credit Suisse report.

That has resulted in a widening income divide in the country. China’s Gini coefficient – a measure of inequality from 0 to 1, with 0 being perfect equality – has hovered between 0.46 and 0.49 over the past two decades. A level of 0.4 is usually regarded as a red line for inequality.

And some experts say that might be underestimating the problem.

The wealth gap is even starker. The wealth Gini coefficient, which rose from 0.599 in 2000 to 0.711 in 2015, eased to 0.697 in 2019 before rising again to 0.704 last year, according to the report.

Just last year, Premier Li Keqiang said the nation had 600 million people living on a monthly income of 1,000 yuan (US$154), which is barely enough to cover monthly rent in a mid-sized Chinese city.

Cai Fang, chief expert of the National Think Tank at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said last month that China’s Gini coefficient indicated that there needed to be a better distribution of income.

“Some of the [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development] countries managed to keep the Gini coefficient under 0.4 through taxes and payment transfers. Therefore, China needs to use the redistribution tool to improve the income distribution structure,” Cai said.

China’s wealth gap threatens Xi’s post-pandemic economic plan

Some Chinese academics have long warned of the risk of conflict and chaos from allowing people in certain areas to get richer faster and form a “new bourgeoisie” of millionaires or even billionaires.

Most of the millionaires or billionaires, particularly in the last decade, have emerged in coastal regions and the private sector.

One of those richer areas is Zhejiang, a coastal province home to a thriving private sector and the headquarters of Alibaba Group Holding, which owns the South China Morning Post.

In July, the province unveiled details of its plan to build itself into a pilot zone for common prosperity by 2025. It will strive to reduce disparities in residents’ incomes and regional development, and form an “olive-shaped social structure” where middle-income households are the mainstay of the economy.

According to the plan, the annual per capita disposable income of all residents in the province will reach 75,000 yuan by 2025, and 80 per cent of residents will have an annual household disposable income of 100,000-500,000 yuan, with the income gap between urban and rural residents to be kept at a “reasonable” level.

Ding Shuang, chief economist for Greater China and North Asia at Standard Chartered Bank, said China’s focus in the past had been economic efficiency rather than fairness, and allowing a small number of people to get rich first was a very successful strategy in pursuit of this goal.

“But China is a socialist country, the essence is the pursuit of common prosperity. Now even the capitalist countries are emphasising the need to reduce the gap between the rich and the poor, so China certainly cannot lag behind,” he said.

“China is now more inclined to fairness. But fairness does not mean returning to the egalitarian practice of everybody eating from the same big pot during the Mao [Zedong] era. China is trying to narrow the excessive disparity between the rich and the poor.”

Ding Xueliang, from the BoYuan Foundation, agreed that China needed to learn from the past without returning to distant doctrine.

The government should not monopolise all the profitable sectors and should continue to welcome foreign investment, he said.

“I do not think that the widening wealth disparity in China should continue to evolve, but the country needs to learn from the past lessons on how to achieve it,” he said.

One of the major points of interest from last week’s meeting is the stress on the “third distribution” scheme, building on the first distribution of salaries and the second of tax and government fees.

Under this additional scheme “excessive income” and “unreasonable income” would be regulated, and high-income groups and companies would be encouraged to “give more back to society”.

The wording of the committee’s statement triggered concerns that big companies might be forced to donate money, possibly to government-backed funds or NGOs, few of which are independently operated.

Ding Shuang, from Standard Chartered, said the aim of the third distribution idea was to use moral force to encourage people to give back to the community.

“This is supposed to be voluntary, but I think a lot of rich people – even though they have done quite a lot of charitable work – will be under pressure and I think there may be more rich people giving money away,” he said.

Nevertheless, taxes would remain the biggest tool to narrow the wealth gap, he said.

Some academics are already proposing on state media that the government should impose wealth taxes, including on property and inheritance.

Work less, spend less: has Covid-19 changed Chinese consumers?

One day after the top leadership meeting, tech giant Tencent announced that it had created a 50 billion yuan “common prosperity” fund to help low-income groups, improve health coverage, boost rural economic development, and support grass-roots education.

The vagueness of the “unreasonable income” had also raised concerns among businesspeople, Ding Xueliang said.

“Entrepreneurs from the private sector will always say their achievements are based on the market and their hard work, but in China’s business environment, the government can easily catch them out on something,” he said.

“That’s why many entrepreneurs are worried – when the authorities can catch them out, there are more than a dozen ways to punish them.”

The common prosperity concept covers not only income, but also access to public services. That means that the privatisation of public services such as education, elderly care, and medical care will recede, and the government will emphasise the role of inclusiveness and affordability among these service providers, and be strict in monitoring prices, according to Yue Su, principal economist at The Economist Intelligence Unit.

“Companies need to prepare for the new policy environment, with tax enforcement being stricter and making donations becoming a new norm,” she said.

“The government might also intervene more in wage setting and request companies safeguard labour rights for all types of workers, including gig workers.”

For Ding Xueliang, it is a long way from those days in Boston talking to his fellow students.

“1986 was the very initial stage of the disparity of the rich and the poor, when the enrichment was small-scale and local,” he said.

“Deng Xiaoping had been aware of that, saying in 1985 that ‘we will fail if our policies lead to rich-poor polarisation, and we will really be on an evil path if some new bourgeoisie is created [due to the wealth disparity]’.

“Today it is so different, there are so many emerging industries and people get rich faster and on a much larger scale.”