Natalie Portman’s arms. It’s now impossible to say those three words in a normal voice. Ever since pictures first emerged of the star in Thor: Love and Thunder, no one has quite known what to do. Everyone is spellbound. Here’s a sample set of responses from Twitter: “Filling out passport paperwork. Religion: Natalie Portman as Mighty Thor.” “I will not write horny s*** about Natalie Portman’s arms”. And “Natalie Portman punch me in the face pls”. (I mean, sure, but have you seen the arms? She would literally kill you.)

For her role as Jane Foster in Taika Waititi’s sequel, Portman said she was “asked to get as big as possible” – and big she got. According to her trainer Naomi Prendergast, she did 90-minute workouts at 4.30am for 10 months to achieve her physique. Something that Portman says was “really fun”. But then again, she is an Oscar-winning actor. She drank the protein shakes. She lifted the weights. And she got the guns. And, actually, doesn’t it make sense? Finally we’ve got a female superhero who looks like she could actually throw giant hammers at baddies’ heads.

That the reaction has been so celebratory is intriguing; when it comes to physically strong women, this isn’t usually the case. The You Look Like A Man Instagram account documents the gross things that people say to women in athletics. “Leave the manning to the men”, “you look like you sweat bacon grease”, “good luck with the arthritis” and “dudes don’t wanna date their dads” are a choice few. In the late Noughties, Madonna was savaged for her muscular arms, with celebrity gossip site TMZ variously describing them as “bloodcurdling veiny corpse arms” and “gruesomely muscled arms [that] appear to have been reassembled with the bony remains of a dead cow”. Women are not usually permitted to transgress from the template of ideal femininity. Madonna, of course, committed the double sin of being both physically strong and in her fifties.

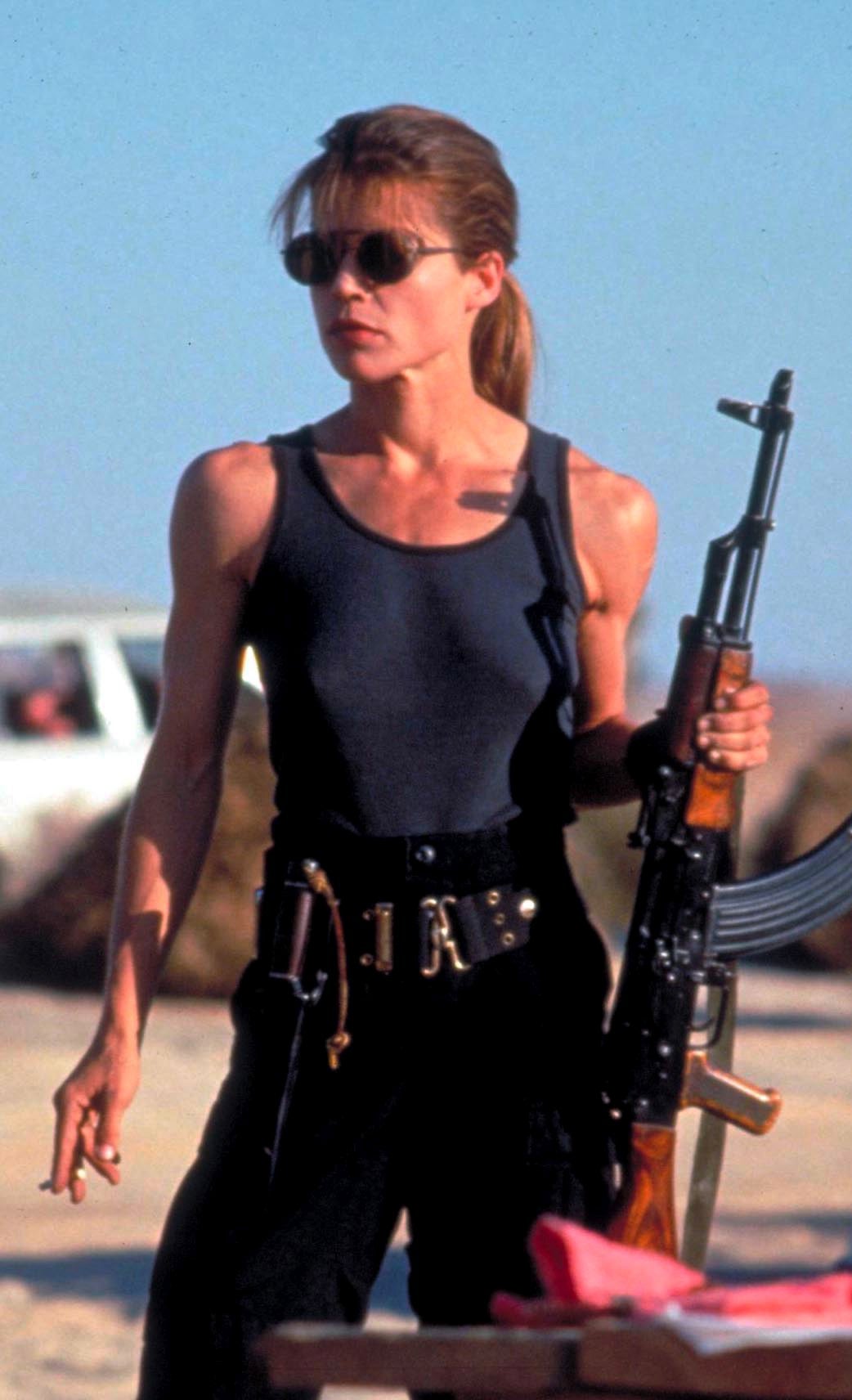

There is a precedent for Natalie Portman’s arms. When Linda Hamilton first appeared on screen in Terminator 2, the first shot we see of her Sarah Connor is of her glistening, taut, bulging biceps as she performs pull-ups on a metal bar. Her physical appearance, so different from women’s bodies in 1991, made cinemagoers gasp. The love for Portman’s arms, though, comes at a time when attitudes towards female strength are changing. More women are taking up weightlifting; there are 32.4 million posts under the #girlswholift hashtag on Instagram. There are many reasons why it’s being embraced: as well as helping to build muscle, it improves your cardiovascular, bone and joint health. Gunnar Peterson, personal trainer to Khloe Kardashian, recommends lifting as the number one way to get lean.

“Muscle pays for the party,” he says. “Muscle is burning all the time. Lifting weights means, post-workout, you’re burning calories at that higher rate than after a straight cardio workout.” Even the least-likely-to-wear-a-sports-bra Spice Girl is doing it: “I’ve always been a bit scared of weights, but it turns out I love them. I’ve even got those special gloves to wear!” Victoria Beckham recently told Grazia.

And yet, in terms of cultural depictions of strong women, the fascination always seems to be drawn from the fact they remain so rare. Or, as Holly Black writes in Elephant magazine: “The term ‘female strength’ is a loaded one… physical fortitude is an accepted facet of male gender roles, but it is still surprisingly hard to find equivalent female counterparts”. Occasionally, it borders on fetishisation. When Barack Obama left office, Vogue marked the occasion with a “farewell to Michelle Obama’s flawless arms”. Her “surreally toned” arms “grew to represent so much more than her personal dedication to fitness: they were also a physical reminder of her ability to roll up her sleeves and get things done” – apparently.

A woman’s appearance remains the number one signifier of her worth to much of the world. It’s a fact that women continue to win Oscars for “uglying up” – putting on weight for roles, or burying their faces in prosthetics. The world hand-wrings when celebrities like Adele and Rebel Wilson lose weight. A woman with muscly arms is a curiosity, but as long as she’s still beautiful, it’s okay. She’s poking at the template of accepted femininity without undermining it in the most fundamental way – by becoming unattractive to men. In this sense, let’s be honest – Portman’s arms are basically really good marketing.

And there’s a danger in that. Women are already navigating a world saturated with Instagram-ready versions of female ideals. The quest to emulate them is both expensive and futile – in Naomi Wolf’s feminist classic of the Nineties, The Beauty Myth, she wrote: “Ideal beauty is ideal because it does not exist; the action lies in the gap between desire and gratification…That space, in a consumer culture, is a lucrative one.”

The problem? Capitalism and patriarchy are a lethal combo. The never-ending quest to curate a perfect version of ourselves has only been amplified by social media, which gives its users the illusion of autonomy as it drip-feeds them expensive trends. In her essay “Always be Optimising”, the New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino describes the tyranny of life as a woman under late capitalism, stuck on a hamster wheel chasing a rigid ideal. Barre classes – an expensive, efficient, painful and results-driven form of exercise – may be making women feel good for the wrong reasons, she suggests. “What it’s really good at is getting you in shape for a hyper-accelerated capitalist life.”

But what if our changing relationship with female strength became a way of breaking free of some of those things? The writer Casey Johnston got into weightlifting after she realised she could “get strong much more easily and quickly than I ever could have imagined; and that lifting weights could be the most fun and validating form of exercise I’d ever tried”. In one of her Ask a Swole Woman columns for Vice (now continued on her She’s a Beast Substack newsletter), she gives liberating advice to her readers. One wants to know how to lose weight; Johnston reframes the question. She writes: “What I want for you is a kinder, more generous, and more expansive goal than the ‘losing weight’ one that the world keeps trying to hand us.” If you follow her philosophy, becoming physically strong can be about claiming one’s own agency and taking care of oneself, in a culture that pushes women another way.

That sense of meaning and empowerment is something echoed by Poorna Bell, an author, journalist and powerlifter. She recently won the 2022 Sports Performance Book of the Year for Stronger, her memoir about her journey to being able to lift twice her own body weight. She wrote on Instagram that “powerlifting isn’t just a sport to me, it’s a metaphor for life. And it has given me sanity and purpose in my body, in a world that strives to deprive me of both”.

In fact, Portman would agree. “To have this reaction and be seen as big, you realise, ‘Oh, this must be so different, to walk through the world like this,” she said. “It’s so wild to feel strong for the first time in my life.” In a world where women’s bodily autonomy is no longer guaranteed, it almost seems radical.

‘Thor: Love and Thunder’ is in cinemas now