Cocaine is derived from the leaves of the coca plant, which is native to Central America. For thousands of years, the leaves were used by the local inhabitants such as the Incas, who chewed or made them into a tea, because of the alertness and energy they provided.

German chemist Albert Niemann eventually isolated the active ingredient in 1859 and it was named cocaine. This was the beginning of the drug’s use as a medicinal and recreational substance in Western culture.

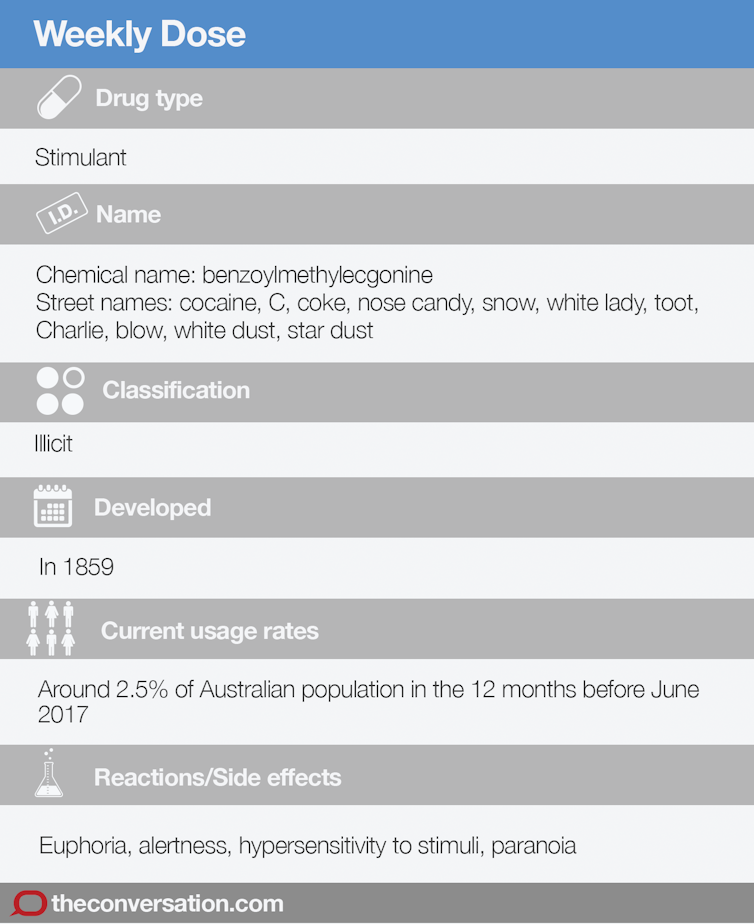

How many people use it

Cocaine is the second most commonly used illicit substance in Australia, after marijuana. Reports of cocaine use in the 12 months to June 2017 more than doubled since 2004 – from 1% to 2.5% (or around 170,000 to 500,000 people).

Read more: Weekly Dose: cannabis has been used medicinally for millennia, why is legalising it taking so long?

The number of people who have ever used cocaine has had a similar percentage increase – from 4.7% in 2004 to 9% in 2016. Cocaine use has reached a 15-year high.

History and use over time

Cocaine gained prominence in the 1880s. Sigmund Freud broadly praised its uses, including in overcoming morphine addiction and treating depression.

Viennese ophthalmologist Carl Koller performed the first operation using cocaine as an anaesthetic on a patient with glaucoma, which led to its use as a local anaesthetic.

But, soon after, practitioners began reporting side effects. Cocaine doses were administered at such high concentrations that there were 200 cases of intoxication and 13 deaths (in around seven years) as a result.

At the 1912 Hague International Opium Convention cocaine (and heroin) was added to the drug control treaty as problematic substance. This sparked the introduction of new drug control laws relating to cocaine in various countries.

Cocaine use decreased after this, but later experienced a surge in popularity in the 1970s, peaking in the 1980s. During this time, cocaine was associated with celebrities, high rollers and glamorous parties.

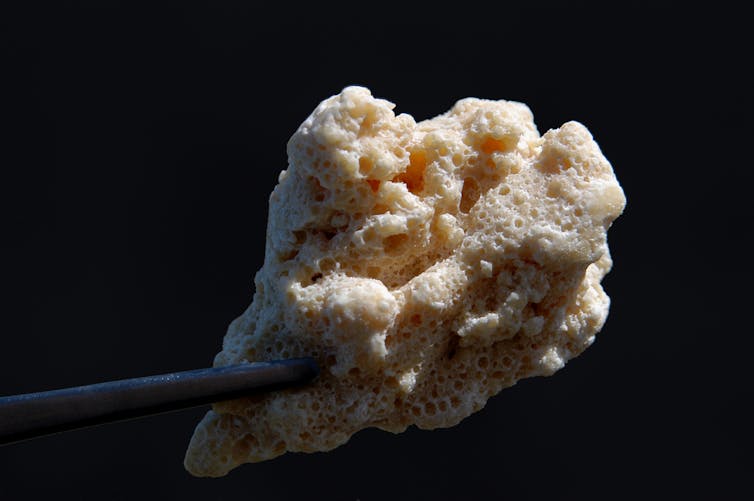

Then a new, crystallised form of cocaine (crack cocaine) was developed. Crack cocaine is processed with ammonia or baking soda, producing a solid “rock” version of the drug which could be smoked.

Not only was crack cocaine more potent, but the effects of the drug (typically after smoking) were felt faster. It was also much cheaper, which allowed it to spread quickly into poorer communities. Its use became recognised as an “epidemic” around 1985, which lasted for ten years.

How it works

The nervous system uses chemicals called neurotransmitters to communicate. These move across the space between two nerve cells and bind to receptors on the receiving cell.

Neurotransmitters do different things. Dopamine, for instance, is involved in the reward system of the brain. It creates feelings of pleasure and contributes to motor control, reinforcement and motivation.

Read more: Explainer: how do drugs work?

The more neurotransmitters are present in the space between two cells, the more can bind to receptors and have a stronger effect. When the body no longer needs the neurotransmitter in its system, it gets reabsorbed into the cell that released it. This is called re-uptake.

One way to increase the level of a neurotransmitter in the brain is to prevent this re-uptake process from occurring. Cocaine inhibits the re-uptake of dopamine in the brain. The resulting increase in dopamine can cause heightened feelings of pleasure and well-being, among other effects.

Some evidence suggests cocaine also inhibits the uptake of the stimulant norepinephrine and the mood regulator serotonin.

Nerves also communicate through electrical signals. Cocaine inhibits electrical communication. In this way, it also works as an anaesthetic by blocking communication between peripheral nerve cells. Cocaine produces a numbing effect when applied to mucous membranes such as the mouth, throat and inside the nose.

How much it costs

The average price for cocaine is around A$300-$350 per gram. That’s A$50 more per gram than methamphetamine (ice). In 2017, Australia ranked as the most expensive country to buy cocaine.

Read more: Weekly Dose: ice and speed, the drugs that kept soldiers awake and a president young

How it’s used

Cocaine is used primarily as a recreational drug. In Australia it’s most commonly snorted. Injecting, swallowing and smoking are less common.

How it makes you feel

The effects of cocaine depend on the dose, form, method of use and what the cocaine is cut with. Cocaine is commonly taken in doses of between 10mg and 120mg. A high lasts between 15-30 minutes and has a half-life (time required before 50% of the drug has left the user’s system) of one hour.

Lower doses will cause a person to experience increased heart rate, body temperature and blood pressure. Cocaine also brings out feelings of euphoria, confidence, giddiness, alertness and enhanced self-consciousness.

Higher doses can cause additional effects such as sleep deprivation, hyper-vigilance, anxiety and paranoia.

Some people who use cocaine may also experience tactile hallucinations. A common example of this is the feeling of bugs crawling on the skin.

Using cocaine over a long time or in binges may lead to depression, irritability, disturbances of eating and sleeping, and tactile hallucinations.

Cocaine is also very addictive. Withdrawal symptoms last up to ten weeks.

Cocaine can cause severe heart and neurological issues, and even death, when taken in too large a quantity.

Recent data show that seven people died due to cocaine overdose in 2013 in Australia.

Other points of interest

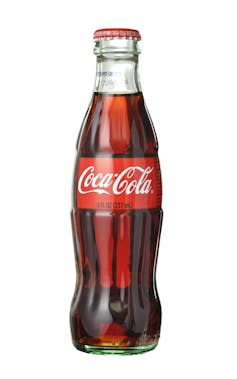

In the 1880s in the US, cocaine was included in numerous medicines, and even in Coca-Cola. Coca-Cola had about 60mg of cocaine in a 250ml bottle.

In Colombia, Mexico and Peru, possessing small amounts of cocaine for personal use is decriminalised.

One of the more recent concerns about the resurgence of cocaine is the potentially deadly effect it has when cut with fentanyl, a potent opioid. A number of recent drug overdoses in Sydney have been linked to heroin cut with fentanyl, highlighting its deadly effects. While this hasn’t yet become popular with cocaine, it very well could.

Read more: Prince's death from fentanyl is only the tip of the global overdose iceberg

Jason Ferris is the chief biostatistician for the Global Drug Survey, founded by Adam Winstock. He has received funding from National Health and Medical Research Council, The Australian Research Council, the Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education, Queensland Government, Australian & New Zealand Association of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgeons, Tasmanian Department of Health and Human Services, Criminology Research Grant, Victorian Law Enforcement Drug Fund, Department of Health and Ageing, VicHealth, Australian National Preventive Health Agency

Barbara Wood and Stephanie Cook do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.