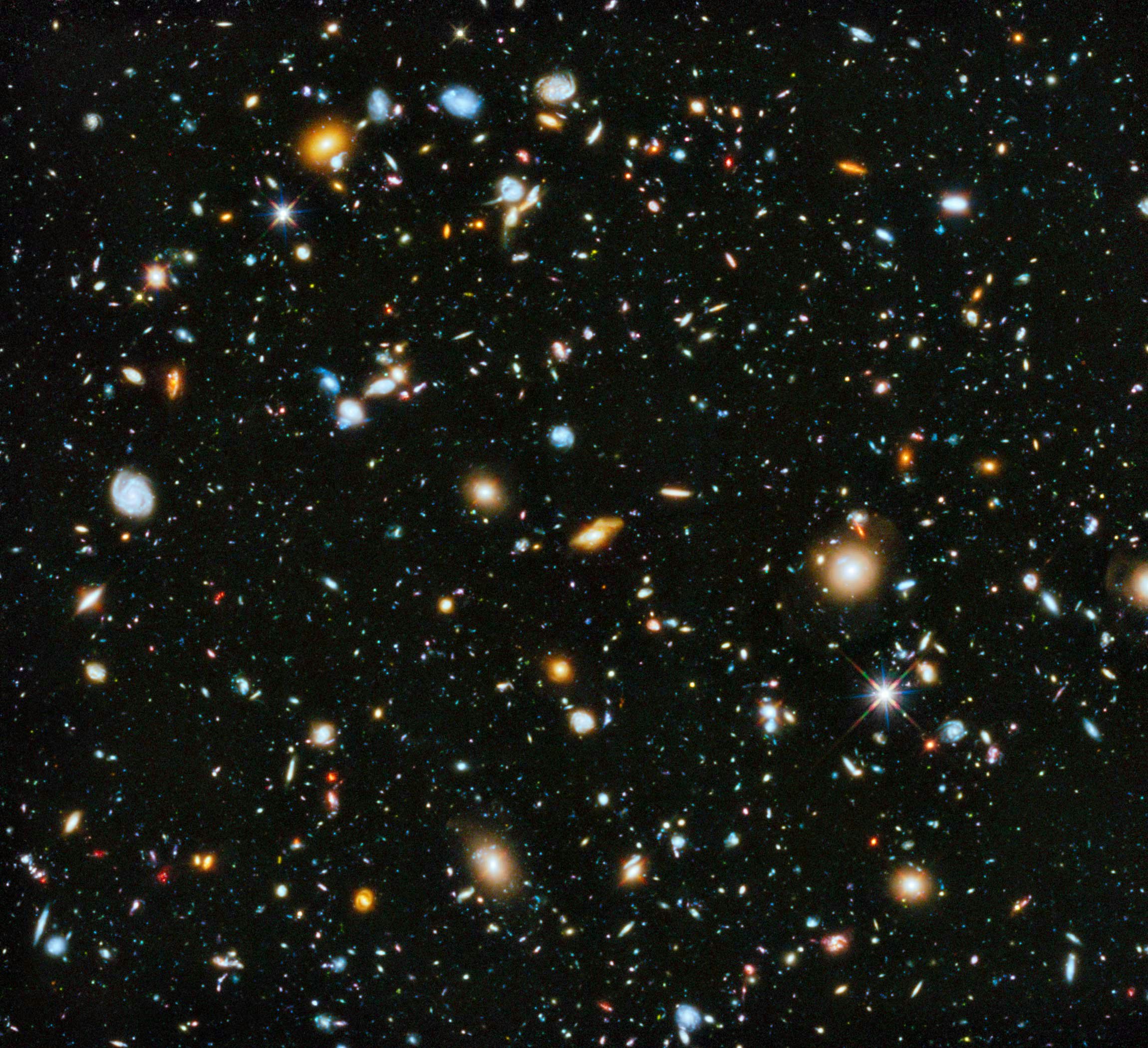

NASA’s venerable Hubble Space Telescope has taken thousands of images across the last three decades, but perhaps none is more iconic than the Hubble Deep Fields. Within a small space of the sky, thousands of galaxies are visible in a single frame, many from the early universe. They have been used to study our cosmic origins.

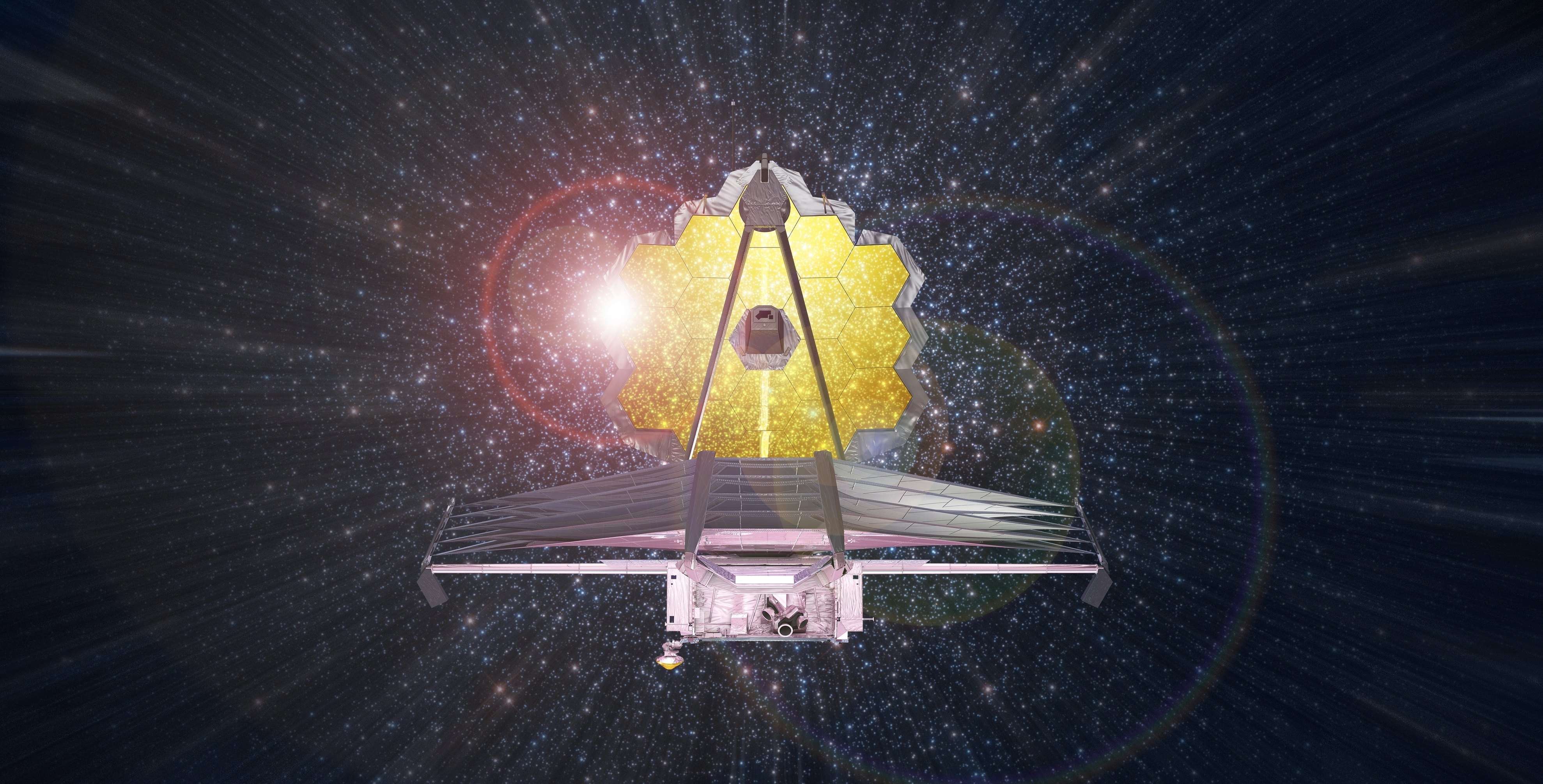

When the James Webb Space Telescope begins its science operations this summer, one of its first projects will be a similar blank field survey. A survey called the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science, or CEERS, will give scientists the first glimpse of this powerful new telescope’s capabilities in detecting extremely distant galaxies. And it does that by looking at what might seem to be an uninterested target — a patch of the sky with nothing bright in it.

“We’re not pointing at a particular object; we’re just looking at a place in the sky,” Steven Finkelstein, the principal investigator of CEERS, tells Inverse. The aim is to survey a region of the sky where there isn’t a lot of light coming from nearby sources so they can see very faint (and very distant) objects. So they chose a patch of sky to survey where there aren’t any giant galaxies and that’s far away from the plane of the Solar System and the plane of the Milky Way, as these areas are bright too.

They landed on a patch of the sky in the northern hemisphere that Hubble previously surveyed in a project called CANDELS. But unlike Hubble's deep field images, which were built up over extended time frames, the work with Webb will use much less observing time.

“The Hubble Ultra Deep Field took hundreds of hours with the Hubble Space Telescope staring at one single place in the sky,” Finkelstein says, but CEERS will be different. “With CEERS, because it is what is called an early science release program we weren’t allowed to be that big. So we’re not staring nearly that long.” (An early release science program is one of the first test programs run when Webb begins operations.)

Why JWST will look at the Hubble Deep Field

The team is trying to get as much data as possible from a relatively brief series of observations using Webb. Each observation will be for just a few hours, with 10 different locations observed and stitched together to create a map of the area.

Another difference is the wavelengths the surveys work in. Hubble looks mainly in the visible light spectrum, but Webb looks in the infrared. That’s useful as it means data from the previous Hubble observations can be combined with the new observations to get a more complete picture of the region.

The great strength of surveys is that space is very, very big, and we don’t know what’s out there until we look at it with instruments like those on Webb. Once a survey is completed, it can help identify objects for further study. “A big component of CEERS is finding interesting targets to follow up in the future,” Finkelstein says.

As one of the first science programs to work with Webb, CEERS is more than a way to gather information on a patch of the sky. It’s also a test of Webb’s capabilities to try out what scientists call parallel observations — observing one target with multiple instruments simultaneously. The survey will look not only with Webb’s infrared cameras, called NIRCam and MIRI but also with a spectrograph called NIRSpec.

“It’s more science per hour,” Finkelstein says. In practical terms: In addition to images of the field, the team will get data called spectra for around a thousand different galaxies collected at the same time. Spectroscopy breaks down light into different wavelengths to see the composition of different objects — and that means spectra can tell researchers what galaxies are made of.

Two surveys will follow CEERS during the first year of Webb’s operations: the Next Generation Deep Extragalactic Exploratory Survey, or NGDEEP, and the James Webb Space Telescope Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey, or JADES. These will look at areas of the sky next to and on top of Hubble’s Ultra Deep Field, respectively. So these are areas that astronomers have documented before — but not in the infrared, and not in the depth at which these surveys will be looking.

The ambitious goal of these surveys is to search for some of the earliest galaxies in the universe. Because light takes time to travel to us, looking at extremely distant targets is like looking back in time. And if Webb can observe galaxies that are far enough away, it can gather data on how the first galaxies formed after the big bang. It’s like a time machine for peering back at the universe in its infancy, and it could help us understand more about how our universe evolved than ever before.