Long before Dream Theater or Tool fused prog and metal, Rush were serving up long, intricate, lyrically mind-bending songs that mixed heaviness with intelligence. In 2013, as the Canadian trio geared up for a reissue of their iconic 1976 concept album 2112, bassist and vocalist Geddy Lee looked back on the history of the band who helped invent progressive metal.

Geddy Lee has a knowing smile. We’re sitting in the lavish surrounds of a room at one of London’s more exclusive hotels. And the subject that’s come up is how Rush are continuing to influence succeeding generations of metal bands.

“It’s nice to know there are young musicians who like what we’ve done,” says the bassist/vocalist. “It’s flattering that these people are taking what we once did and developing it for the modern age.”

When it comes to the birth of progressive metal, Rush have strong claims to be seen as the true pioneers of a style of music that has been taken by Dream Theater, Meshuggah, Cynic and Tesseract, to name but a handful. “I can’t say I’m familiar with the new crop of bands coming through, but all I can hope is that they enjoy the sort of career we’ve had. And stick to what they believe in as much as we’ve always done.”

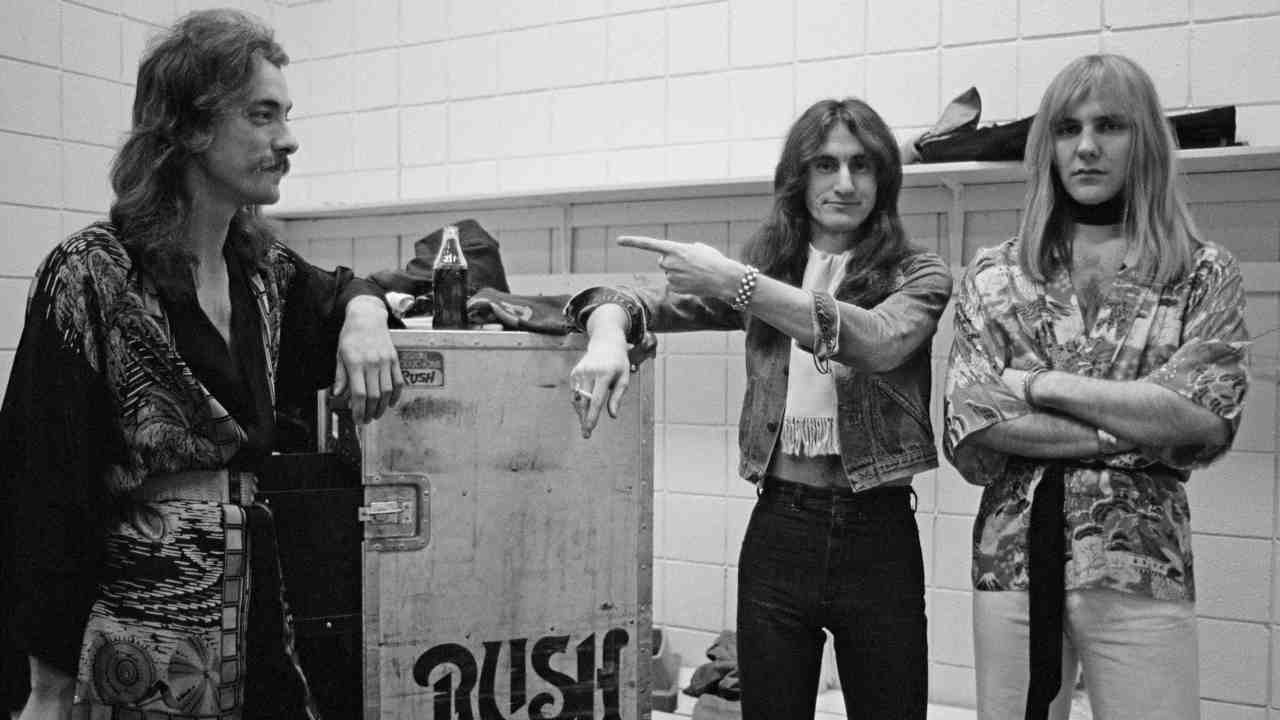

For Rush, it all started rather unpromisingly in Toronto during August 1968. Guitarist Alex Lifeson put together the first lineup with bassist/vocalist Jeff Jones and drummer John Rutsey. Within a few weeks, Jeff was replaced by Geddy.

“I was a school pal of Alex’s and he asked me to come into the band,” explains Geddy. “But it wasn’t plain sailing back then. We went through a lot of different lineups over the next couple of years, with people coming and going. I don’t think we quite knew what we were doing. In our minds, we were the Canadian Led Zeppelin. In reality, we were probably seen as a bit sad. But at least we got to play regularly in local bars and at high-school dances.”

In May 1971, Geddy, Alex and John stabilised, and Rush were born as a power trio. Two years later they released their debut single. It was a cover of the Buddy Holly classic Not Fade Away, with the Geddy/John song You Can’t Fight It on the B side.

“It wasn’t a success,” laughs Geddy. “We didn’t get much radio airplay, and the media in general was indifferent to it. In fact, such was the lack of interest in us that we couldn’t even get a record deal. We were forced to start our own label in conjunction with our manager, Ray Danniels.”

By 1974, the band had released their self-titled debut album, which got noticed by one radio station in Cleveland, Ohio. “We got little support at home. But WMMS in Cleveland picked up on the song Working Man. Donna Halper, one of the DJs at the station, gave it a lot of airtime, for which we shall always be grateful.”

As a result of this exposure, Rush got signed by Mercury, though this breakthrough was dampened by John leaving the band.

“John had health problems; his diabetes meant he wasn’t very much into touring. So there was no falling out; he simply felt it was in all our best interests for him to bow out.”

John made his last live appearance with the band on July 25, 1974 in London, Ontario. He died on May 11, 2008, from a heart attack brought on by his diabetic condition.

The man chosen to replace him was Neil Peart, who had just returned from living in England, where he’d hoped (but failed) to make his mark as a drummer. He was a member of Hush, another Canadian band, when he was persuaded to audition for Rush.

“He turned up wearing shorts and driving a battered old car. He also had his drums stored inside trash cans. It was all very amusing, but I was very impressed with his drumming technique, and also liked him as a person straight away. Alex was a little less sure, but I managed to talk him round.”

Neil officially joined the band four days after John’s farewell performance. On August 14, he played his first gig with Rush. It was also the trio’s debut show in America, as they opened for Uriah Heep and Manfred Mann in Pittsburgh.

Neil quickly assumed the role of writing lyrics for second album Fly By Night, released in 1975, and he immediately made his presence felt. There was a definite shift towards fantasy and science fiction, as was showcased on the band’s first epic track, By-Tor And The Snow Dog. This move, which was also mirrored by a more complex musical vision, was even further in evidence later the same year when Caress Of Steel was released, which featured two more examples of their growing connection to sophisticated and imaginative ideas, namely The Necromancer and The Fountains Of Lamneth.

This was supposed to be Rush’s big break- through album but it was a commercial failure. Tickets sales on the subsequent tour were poor enough for it to be blunty labelled the Down The Tubes Tour. “We’d turn up at venues and sometimes they didn’t even expect us. Other times, there was no publicity at all, so we never played in front of big crowds. It was as if everyone – record company, management – had given up on us. Nobody seemed happy with what we were doing musically, and wanted us to return to the simpler blues-rock on the first album. We were bracing ourselves to be dropped by Mercury.”

However, going against the grain and showing they were ready to ruffle feathers in the process, Rush refused to listen to the business heads, instead going even further than they had done on Caress Of Steel. The result was the landmark 2112 album, which had the first side totally dedicated to the 20-minute-plus title track, which has a theme of freedom against tyranny in the year 2062.

The album captured the imagination and was the first from the band to chart in the Top 100 in America. It got to No.62, while in Canada it was a chart topper. The UK also took serious notice of what Rush were doing, even if they didn’t make the mainstream charts.

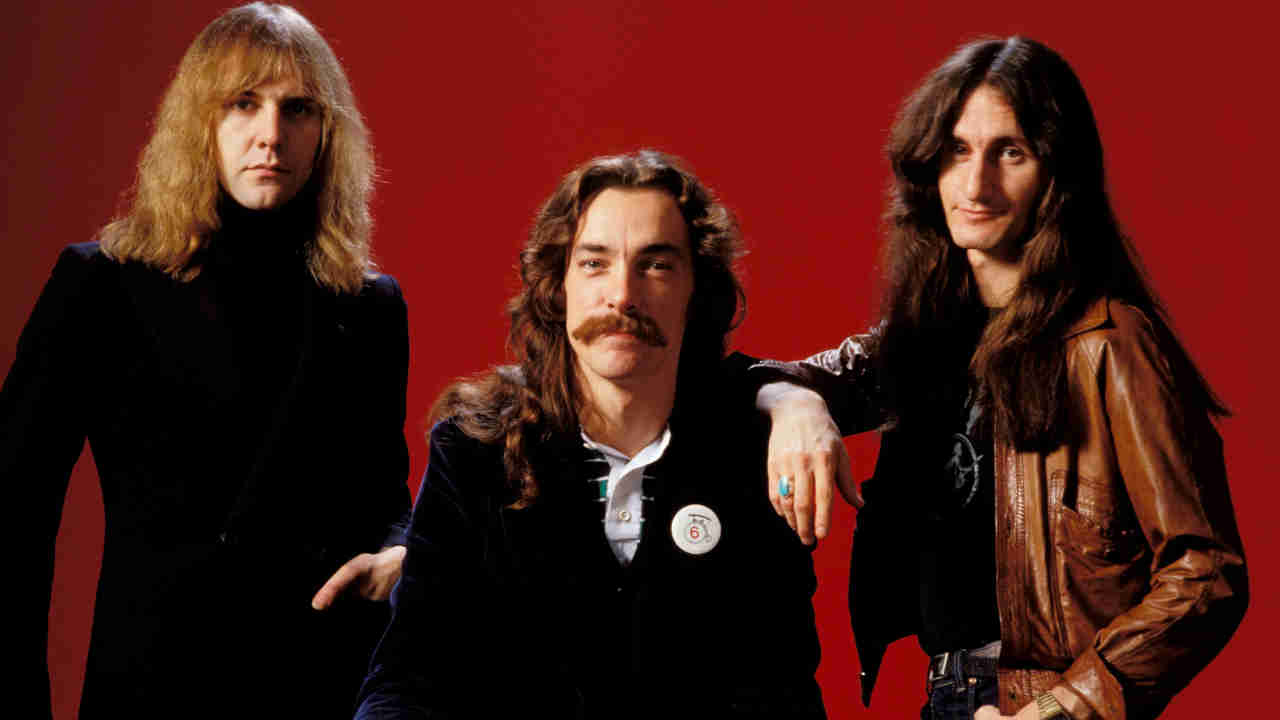

“It was an important moment for us because we’d shown that we did know what to do, and there was a growing audience out there for Rush music. We weren’t arrogant enough to think we were suddenly the most important band in the world. We just knew we were – ha! But if you look at what we were wearing back then… we had no fashion sense!”

Over the years, 2112 has come to be regarded as a standard-bearer for progressive metal, and Geddy recognises its appeal. “To us this is just another album on the way, albeit one that made a difference. But so many fans and musicians see it as some sort of turning point. All we can do is be grateful for the way it’s continually received.”

However, the album led to controversy surrounding the band. When Neil publicly stated that his lyrics were inspired by the ‘genius of Ayn Rand’, some parts of the press labelled them Nazis. This is because of novelist Rand’s own right-wing tendencies. But it was a fallacious claim, and Geddy is still confused and puzzled by such attacks. “We had to endure a lot of interviews where the journalist was out to prove we were Nazi sympathisers. Nothing could be further from the truth, and anyone who took the time to study Neil’s lyrics could never make such a connection. The good thing was that our fanbase was expanding, and we saw no signs of Nazis turning up at our gigs.”

The release of the double live album All The World’s A Stage in 1976 saw the band finally make their debut on British stages. They did seven shows in June 1977 on the tour to support this first live record. “It was incredible to finally have the chance to play in the country which had so influenced our music. At the time, we were on the way to Rockfield Studios in Wales to record the album A Farewell To Kings, so grabbed the opportunity to play live. We also introduced keyboards on this tour, and it was our last one where the setlist was varied every night. We became boring after that and generally stuck to the same songs for each gig.”

A Farewell To Kings was released in 1977 and became the first Rush album to sell over 500,000 copies in the States. It was also the first to make the UK charts, getting to No.22. This album, and 1978’s Hemispheres, marked a turn towards introducing keyboards and synthesisers.

“I was really interested in all the developments in that area of music. Things were moving very fast and I liked what it might do for our music. Alex wasn’t at all enthusiastic. Well, he was the guitarist, so felt we should still be focused around that. But I really believed that if we were to have anything to offer in the new decade, then what we needed to do was explore different sounds.

“We’d also discovered more progressive bands like Yes, Van der Graaf Generator and King Crimson. They inspired us to think about making music more complex and challenging. The trick was to find some way of combining these influences with our own personalities, so what you got was definitely still about us.”

Just how much Rush had moved forward became clear on 1980’s Permanent Waves, when they introduced elements of reggae and new wave into the music. Going back to shorter songs, they enjoyed their biggest success yet, as songs like The Spirit Of Radio proved they had much to offer at a time when some established bands were struggling to come to terms with the changes in the musical landscape.

They were to ride even higher the following year when Moving Pictures gave them their biggest album to date, selling over four million copies in America alone. It appeared that their reinvention had been a triumph. They were now accepted as doyens of a new hard-rock approach, and they’d done it without disenfranchising their diehard fans.

“It was a gamble, and we could have ended up with no audience, losing the old-school ones without getting any new faces. But thankfully that didn’t happen. I think it’s because those who’d been following us for so long knew we’d always adapted our style, yet we still sounded like Rush.”

In 1981, the release of Exit… Stage Left, yet another double live album, marked the end of another chapter in Rush’s diversifying career. By 1982’s Signals, synthesisers were almost the dominant instrument in the band, and this continued throughout the decade. For 1984’s Grace Under Pressure, long-time producer Terry Brown, who’d worked with them since Fly By Night, was no longer involved. “We never fell out with Terry, but it was decided by all parties it was in everyone’s best interests to move on.”

At the end of the 80s, Rush had left Mercury and signed to Atlantic, and this saw a return to a more guitar-oriented approach on the albums Presto (1989) and Roll The Bones (1991).

“By the time we did Presto, I was getting sick of technology and wanted a return to a more basic approach. We were lucky that our producer, Rupert Hine, agreed, so that’s why it’s more about the vocals than anything else. However, I have to say that the album didn’t turn out the way we hoped. If there’s one album we’d love to do all over again, this is it. The songs are so much stronger than the way they came out. I’m not blaming anyone in particular, it’s just a statement of fact.”

By 1997, when the band had augmented their credibility and success with the albums Counterparts (1993) and Test For Echo (1996), Rush were forced to take an extended break, as Neil suffered a double tragedy. His daughter Samantha died in a car crash in August 1997, and 10 months later, his wife Jacqueline passed away from cancer.

“Neil need time to himself to grieve and reflect on what he wanted to do. Alex and I gave him as much time as he needed. There was never any question of putting him under pressure to return.”

In 2001, Neil said he was ready to go back to work, the result being 2002’s Vapor Trails. The first album since the early 1970s not to have any keyboard or synth parts, it was also unusual because Alex refused to play any conventional guitar solos.

“Again, this was us moving on. But it was a tough album to make, and probably took something like 14 months in all. I’m not sure why we appeared to find this one so hard to make. Possibly because of what Neil had been through, and also because we had stripped so much away from our sound. But we never turned our back on technology because computers were extensively used in the writing and arranging of the songs. It’s just we decided it was time to move on from keyboards.”

After celebrating their 30th anniversary in this current incarnation in 2004, with the release of the covers EP Feedback, Rush returned three years later with Snakes & Arrows. Chart-wise, this was their most successful album in America since Counterparts, reaching No.3. The subsequent tour saw the band returning for their first shows in the UK since the Roll The Bones tour in 1992 – a gap of 15 years.

“It wasn’t our choice to avoid coming over to the UK. Promoters kept telling us that nobody was interested in seeing Rush. We believed them and stayed away. Imagine our surprise when gigs sold out quickly!”

Always regarded as reticent public figures, Rush surprised many when the documentary Beyond The Lighted Stage was released in 2010. This saw the band open up like never before, giving people a significant and unprecedented insight into who they are.

“I think what shocked a lot of people is that we showed we have a keen sense of humour, and we interact with each other by sending ourselves and everyone else up. We don’t take everything so seriously, as most of our fans probably believed we did. We’re not po-faced professors of philosophy, but rock’n’roll musicians. And these days we’re probably more about being comedians who play some music, rather than vice versa.”

The release of Clockwork Angels in 2012 again showed the band were able to bend the rules and move into hitherto uncharted territory, as they brought steampunk influences into their world. Moreover, a novel written by renowned steampunk author Kevin J. Anderson (a friend of Neil) was published to coincide with the album’s release. It was based on the story that runs through the songs, and was more proof that Rush are always looking for ways to push the envelope.

“We still don’t want to stand still and repeat ourselves. Even at our advanced time of life it is all about making the right choices, so we keep everyone – especially ourselves – on our toes.”

It says much for Rush that as they approach the 40th anniversary of this lineup, they are once again seen as being at the cutting edge of music, and are influencing so many in the world of metal. “I don’t think about things like the 40th anniversary. We have no plans to celebrate it. We did enough for the 30th. So, if anything is being planned, it will be without our involvement. We are still looking forward, not back.”

So, just what is the secret behind Rush’s enduring career, and how have the trio managed to stay together for so long without killing each other?

“It’s not been easy! Of course, there are moments when we’ve fallen out. But the trick is that we all know how well we work together. We have also become very good at giving each other space to breathe. Ultimately, we are three individuals who can come together and create something special. But it doesn’t take over our lives. And at the end of the day, we can still have a good laugh about anything. Perhaps that’s the secret to longevity: learn to laugh!”

Originally published in Metal Hammer issue 241, February 2013. Rush retired in August 2015, following a farewell tour. Neil Peart passed away in 2020