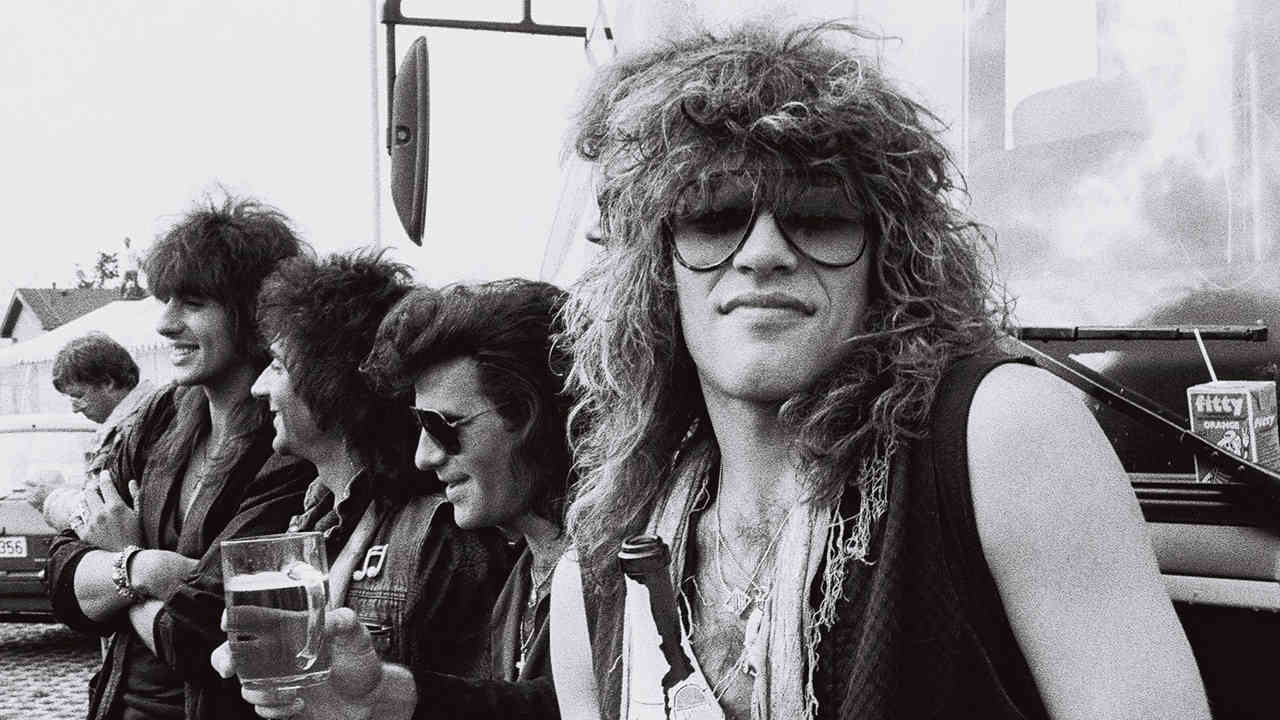

It’s 1986, and a Mexican restaurant called Break For The Border in Central London is the location for a celebration. It’s time for Bon Jovi to get due credit from their record label, Mercury, for the fact that third album Slippery When Wet has turned them into household names. After the first of multiple sold-out nights at the Hammersmith Odeon – now the Apollo – the assembled media, hangers-on, musicians and general glitterati of the English rock scene have been crammed around snaking tables, drinking margaritas and downing tequila shots. No expense has been spared.

Suddenly, the creaking PA system is cranked and the familiar strains of You Give Love A Bad Name blare out, as the band arrive, surrounded by label types and security. From the midst of this pushing, shoving, self-important crowd, Jon Bon Jovi lifts a hand, clenches it into a fist, and waves it triumphantly at the journalists who’d supported the band from the beginning.

“We did it!” he shouts, unable to stop the tidal momentum that takes him ever closer to the VIP area, from which all save for a chosen élite would be excluded for the rest of the night.

Right then and there, you feel that the ‘we’ isn’t merely a reference to Jon, the band or the label. But to everyone who’d believed for so long. Bon Jovi had made it into the big time, and things would never be the same again. It had all been so different just a few months earlier, when I jetted out to New Jersey, to listen to what would be the Slippery When Wet album, and find out how close Jovi were, this time, to the breakthrough many had predicted for a couple of years.

The band were under pressure. After their self-titled, debut album in 1984 had put them firmly into the trench, everyone took it for granted that 1985’s 7800° Fahrenheit would take the guys over the top, and into the vanguard of platinum-selling bands. It never happened.

“Everything about that second album was wrong,” recalled Jon, as we sat in a rented apartment, facing the ocean in New Jersey. “All of us were going through tough times on a personal level. And the strain told on the music we produced. It wasn’t a pleasant experience. I also reckon we went for the wrong producer. Lance Quinn wasn’t the man for us, and that added to the feeling that we were going about it badly. None of us want to live in that mental state ever again. We’ve put the record behind us, and moved on.”

But the darkness and heavy emotional baggage of the band’s second album had left them scarred. You could tell immediately in the room where the five members were huddled, cracking open a beer or several, munching on anything to hand, and generally trying to give off the atmosphere of confidence and belief, which they wanted to portray to the outside world. Jon was noticeably fidgety. Guitarist Richie Sambora was pacing the floor, as if measuring it for carpet tiles. Bassist Alec John Such was almost hiding in a corner, while drummer Tico Torres thrummed his fingers and keyboard player David Bryan kept himself occupied by idly glancing at the local sports pages. This was the first interview the band had done since finishing the new album, and there was a sense of nervous tension.

“We can’t play you anything yet from the record,” Jon stared and stated. “It’s just not quite ready, and we’re anxious for you to get a feel for the final mix, rather than hearing work in progress. But we’re all very happy with the way it’s gone this time.”

Behind those words was a man with his fingers crossed. He and the band – together with producer Bruce Fairbairn – felt within themselves that here was the best album they’d made. But the acid test was about to drip, drip, drip. Would the outside world agree?

There were questions that had to be faced: is it true that Bon Jovi were close to being dropped by their label, before they even made a third album? Why bring in outside writer Desmond Child? Were the band thinking about getting rid of their rhythm section? All these demanded answers. The only way to get the freedom to turn this into an interview with purpose was to leave the band behind and brace the wind whipping up over the beach. Jon and I sat down on the shale, alone save for a few curious seagulls in the distance, and what followed was an honest, illuminating dialogue on the state of Jovi.

“Were we nearly dropped by the record company?” repeated the bemused frontman, when confronted with the rumour. “Not as far as I know. That’s something you’d have to ask our managers – Doc McGhee and Doug Thaler – they deal with all the business angles. We’ve had nothing but support from Polygram [their label, now known as Mercury] on this record. They’re very keen to give it a real push. Of course, you’re always under pressure to deliver the best possible album, but they wanna see us sell a million.

“What we’ve been trying to do is to balance out the need to sell a lot of copies with the desire to stick to our artistic guns. But it’s what you expect when you sign up for a big company. They’re not a charity. It’s all a learning process. Every day we find out something new. I remember when we did our first video, for the song Runaway. We were in a big office at the label, and one of the business guys said, ‘The great thing is that this video’s recoupable’. I had no clue what the hell he was talking about, and just thought, ‘Wow. That must be good’. Only later did I find out that it meant this cost us money.

“So, you gradually get used to turning the label to working to your advantage. We’re still learning about this. But we’ve got what we wanted on this record, and I can’t really believe that would have happened if they wanted rid of the band.”

But what would be the consequence of this album not selling?

“Hey, there are jobs going in the local pizza parlours! Or maybe I can come over to England and make coffee for all you guys!”

Jon’s chuckle was genuine. He’d always believed in himself, and in his destiny to become a ‘rock star’. But he also wanted to earn respect as a musician too.

“My heroes are people like Southside Johnny and Bruce Springsteen. Their songs tell valuable stories. These guys are for real. I can relate to them, and the way they work. I come from the same blue-collar background. I’ve grafted for everything. People seem to think that I’m a pretty boy who just got lucky. I’ve swept studio floors, done all that kinda thing.”

Which brings us to the fact that Jovi worked on this album with Desmond Child. The notion of bringing in an outside songwriter was the sort of thing done by pop artists, not credible rockers. Surely, this wasn’t the band’s idea?

“To some extent it was our choice. I liked what Bryan Adams had done with Tina Turner [they duetted on Adams’s It’s Only Love], so I suggested we do something similar – I write a song for someone like her, and then we do the song together. But that got changed, and our A&R guy [Derek Shulman] came up with Desmond’s name.

“We’re growing as songwriters, learning things. What’s wrong with collaborating with people like him, who can help to give us the extra 10 per cent out of a song? Actually, he’s involved with only three tracks on here – Livin’ On A Prayer, You Give Love A Bad Name and Without Love – and, in each case, he hasn’t tried to change what we are, but to refine it slightly, to suggest extra ways that we could wring a bit more out of what we had.

“This is the way I see it: you don’t think that George Martin had an input into what Lennon and McCartney wrote? You don’t think Andrew Oldham helped out Jagger and Richards with a little guidance? However good you may think you are, it can’t be a bad thing to work with professionals; those whose experience can bring out the best in you. Working with Desmond has done myself and Richie a power of good. I see him as almost an extra producer, someone we could bounce ideas off. But, once you hear these songs, you’ll know that it’s Bon Jovi, not Desmond Jovi.”

Bon Jovi were far removed from rock star grandeur when they began the process of putting together their third album. Songwriters Richie and Jon weren’t holed up in a mansion with hot and cold running indulgence. Oh, no…

“We wrote it in Richie’s mother’s basement. That’s where we were at. His parents both worked, so the house was empty during the day. Richie was playing the bars on the cover circuit, trying to make ends meet – you see, we’d barely made any money at that point. I would drive over there with some pizza, bang on the door, and wake him up at one in the afternoon. We’d write until six in the evening, when his folks came home. It was just us. We knew who we were. We knew it was going to be a different producer who would capture that live element. And we were going to have stories to tell.”

The story that inspired Wanted Dead Or Alive went back to the band’s exhaustive tour in support of the 7800° Fahrenheit album.

“I was on the tour bus and couldn’t sleep, and was staring out of the window, thinking: ‘This is great, but it’s an odd existence.’ You don’t know were you are. You’re living in truck stops, sleeping on the bus, showering at a gig. We were thinking of songs like Turn The Page by Bob Seger, and how those songs were storytellers doing their best storytelling. I talked to Richie about the concept, he worked up the riff almost on the spot, and we knocked it out in two or three hours.”

Livin’ On A Prayer, meanwhile, is locked into the working class ethic around which Jon grew up.

“I am really proud of that one, because it goes back to the storytelling roots that I was talking about. It deals with the way that two kids – Tommy and Gina – face life’s struggles, and how their love and ambitions get them through the bad times. It’s working class, and it’s real. That’s what most of our fans can relate to, not the limos and groupies. That’s where I still find my heart.

“I wanted to incorporate the movie element, and tell a story about people I knew. So, instead of doing what I did on Runaway, where the girl didn’t have a name, I gave them names, which gave them identity. I wanted to relate those stories to people I’d gone to high school with. Some got married right out of high school. Some joined the service, and now were working somewhere. I wanted to tell their stories, because they could’ve been me, if I hadn’t learned to play guitar. Tommy and Gina aren’t two specific people – they represent a lifestyle.

“As a songwriter I’ve been hugely influenced by someone like Tom Waits, thanks to his cinematic approach. Elvis Costello was another, and storytellers like Paul Simon. Elton John was a big influence when I was a kid, because of Goodbye Yellow Brick Road and Captain Fantastic And The Brown Dirt Cowboy.”

The third crucial commercial element of the record was You Give Love A Bad Name, the second song written with Desmond Child.

“He came down to that Sambora basement, and we wrote something called Edge Of A Broken Heart,” Jon recalled in the early 1990s. That song never made it on to Slippery…, but it went on to be a b-side and is featured on the 2004 retrospective box set 100,000,000 Bon Jovi Fans Can’t Be Wrong.

“The second song was You Give Love A Bad Name. We demoed it up, liked what we heard, but never thought it would be a hit. We’d never had one of those before, so didn’t actually know what to expect. Actually, we were gonna call it Shot Through The Heart [the opening lyric], but then changed our minds.”

And considering the band already had a track with that very title on their debut album, it was a smart move. The song’s believed to have been inspired by Jon Bon Jovi’s brief flirtation with actress Diane Lane in 1985. But, a year later, the singer chose to remain enigmatic about the source, stating simply: “Is it about Diane? Maybe.”

There was little glitz about the process that shaped one of the most important albums of the era. More a lot of guts, grit and grease. Oh, and a spontaneous vox pop, conducted in a pizza parlour. Back we go to the New Jersey beach in ’86.

“Bon Jovi is still very much a grassroots band, OK? After we wrote all the songs for the album, we put them on a cassette and went down to the local pizza place [in Sayreville, New Jersey], hung out with the kids and got their opinions. The reaction was phenomenal. Honestly, the fans were excited by what we were doing – and these are the people who will finally judge, by either buying the album, or not.”

The gathering force from the ocean spray was being more than matched by Jon warming to his subject. The pressures that seemed prevalent in the apartment just a couple of hundred metres in the distance were being washed away by his fervour. When it came to the state of the band, and whether changes were considered, he let fly…

“I know that some people think we should all be pretty boys, and that the image should come first. But do you know how long it took to find the right lineup? It didn’t happen with the snap of a finger. We worked hard at it. We’ve lived together, toured together, been through the shit together. Why on earth would I even consider kicking out one or two members? Everyone does his job – we’re a gang. The five of us.”

With hindsight, I do wonder whether Jon was being completely honest. There seems to have been a deep-seated assessment of the band at all levels, prior to the Slippery When Wet sessions. Almost certainly, it involved an analysis – at least at label level – of whether this ‘project’ could go any further. This notion was backed up a few years later by the man who’d signed Bon Jovi in the first place, Derek Shulman.

“I never doubted that Jovi would be huge,” said Derek, the Scottish-born A&R guru (and former vocalist with prog eccentrics Gentle Giant). “But, if you wanna know how close we came here to canning the whole thing before Slippery When Wet… all I’ll say is that we didn’t commit big funds to it without making sure everything was right. I think you can take it as read that, once we’d satisfied ourselves that the band were doing everything right, then we knew this was gonna be a winner.”

Back on the beach, Jon had similar confidence. “When you hear what we’ve done, then you’ll understand just why I know we’re going to be a big name for the rest of the decade. Things just feel right. On our debut, we were learning how to be a band. With 7800° Fahrenheit, we went through bad times, but they made us stronger. Now, we’re putting it all together. I have to give a lot of credit to our producer this time, Bruce Fairbairn. He’s just been the best we’ve worked with so far.”

Jon’s cousin, Tony Bongiovi, was the man primarily responsible for the debut, while Lance Quinn did the follow-up. However, Fairbairn was the man with whom Jon and the band felt most closely allied.

“We all moved to a two-bedroom apartment in Vancouver for pre-production,” Jon told me. “We quickly realised that Bruce was going to capture the essence of the band live. He was unbelievably anal in his attention to detail. But he gave us this purpose. He believed in us. And the recording sessions went so fast.”

It’s probably true to say that Fairbairn is the most attuned producer with whom Jovi have ever worked. A couple of years after the album’s release, Fairbairn recalled how proud he was of the album.

“I’ve been lucky enough to work with so many different talents, but Bon Jovi may be the finest,” he said. “You never quite know what to expect with a band whom you don’t know – and there was record company pressure to deliver the hits – but they were a joy. People seem to concentrate so much on their success that they lose sight of how good these guys are.”

Over the years, it’s been forgotten how diverse this record is – not so much a pop-rock masterpiece as a hard rock masterclass. “We’ve got a few real surprises here,” Jon remarked, huddling up against the prevailing chill on that beach in ’86. “There’s a song called Love Is A Social Disease that Aerosmith were keen to get hold of. It would be ideal for them, but they’re not having it. Because it’s even better for us!”

The original title of the band’s third album was to be Wanted Dead Or Alive, something they changed only shortly before the album’s release in 1986 . And, as soon as the record was put out, it hit pay dirt – big time. It reached the top of the US chart, and peaked at No.6 in the UK, fuelled by the success of the first single, You Give Love A Bad Name. Suddenly, everyone wanted to know Bon Jovi. The tabloids were enamoured of Jon’s good looks, and the spotlight was turned more on the superficial side of the band than anything deep or meaningful.

“Now, I’m starting to understand just why people have their heads turned by success,” Jon laughed in early 1987, when we made further contact about it.

“It’s been crazy. There is no privacy any more. The attention’s amazing, but we’re no longer able to get peace anywhere. I can now understand what Robert Plant meant when he said that you spend so much of your career trying to get noticed, and then once you make it, then you appreciate that it’s the last thing you want.”

Jon was also a little more open about some of the problems that the band had faced while making the record.

“I may not have said so to you last year, but I did feel under pressure. We were getting a lot of hassle from everyone around us to make the perfect third album. We kept being told that it had to sell, or the band’s career would stall. What kept us going throughout was the belief that we’d done it the right way. We hadn’t come out of nowhere and had a hit single. We’d built this carefully. Especially in Britain. We’re known as a hard rock band with a strong and loyal fan base. So, even if this all blows up in our face tomorrow, those people who were there for us when we toured with Kiss in ’84, and played Donington the next year, will still be there, because we appreciate them, and have never ignored what they wanna hear.”

20 years on, Slippery When Wet has become iconic, selling over 13 million copies worldwide to date. It seems to be the standard by which everything the band have subsequently released is judged. In many ways, it’s the point at which America took on board the lessons Def Leppard had taught in 1983 with Pyromania. Slippery When Wet took these rules and ran with them. And the world noticed. Not just hard rock afficionados, but casual radio listeners and pop fans. But Slippery… has survived and prospered because it is a record with depth, clarity and no little sincerity.

“I look upon it as a career record,” Jon said in the mid-90s. “To me it was part of the ongoing story. I want to be around as long as someone like Frank Sinatra. He’s my role model. I’d love to be half as cool as he was, to be on the scene for half the length of time. That guy’s done nearly 70 movies, toured until he was 80. In those terms, Slippery When Wet was one more step on the road…but it was an important one.

“I rarely listen to our old records. But I heard You Give Love A Bad Name on the radio the other night. I was like, ‘It’s still on the radio, all these years later!’ I saw myself again as a kid, enjoying that moment in time, and you smile. It still holds up.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 94