This article was published online on August 10, 2021.

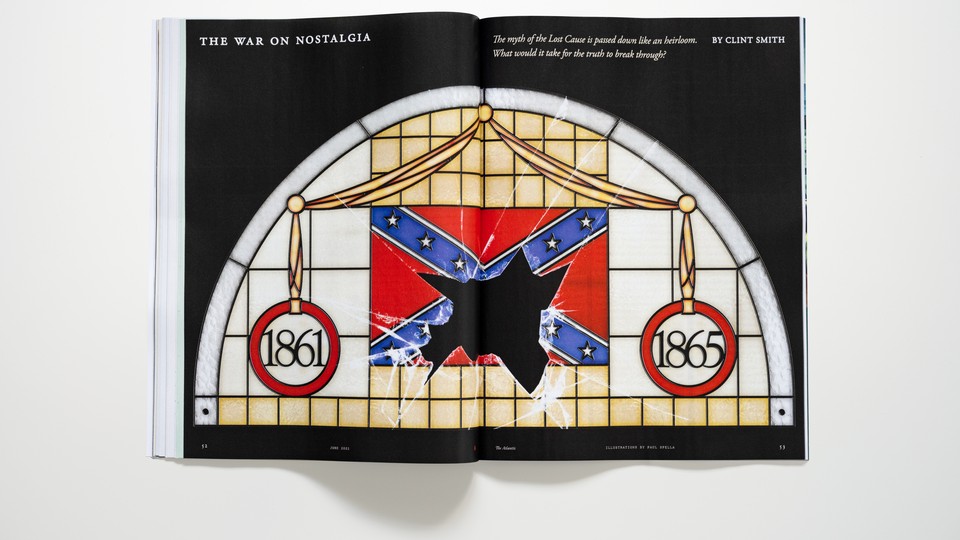

The War on Nostalgia

The myth of the Lost Cause is passed down like an heirloom, Clint Smith wrote in June. What would it take for the truth to break through?

I am a southern white male. I was born in 1953, so I am old enough to remember my paternal great-grandmother, born in 1877 in Langley, South Carolina; my paternal grandfather, born in 1900 in Augusta, Georgia; my paternal grandmother, born in 1898 in Blakely, Georgia; and many other southern kinfolk from a bygone era. My parents taught us that hate was a sin and that Jim Crow was wrong. So I grew up thinking I was not bigoted or racist in any way.

Your article was something of a slap in the face, a wake-up call to recognize how embedded in the world of white privilege and power I actually am.

My father and I got interested in family genealogy in 1998, and we quickly discovered that one of his ancestors had served as a private in the 20th South Carolina Volunteer Infantry from 1863 to 1865. We thrilled at finding microfilm records documenting his service, and learned that he had been taken prisoner at the Battle of Cedar Creek in Middletown, Virginia, on October 19, 1864, and spent the remainder of the war at a prison camp in Point Lookout, Maryland. We also learned that a large Civil War reenactment takes place on the third weekend of October in Middletown. We attended the reenactment every year from 1999 to 2011 and took my son (now 28) and his best friend many of those years. We proudly wore Confederate symbols so that folks would know which side we were on.

My wife had an uncle, now deceased, who was active in a Texas branch of the Sons of Confederate Veterans; circa 1999, he talked me into attending a meeting of a chapter near Atlanta. The members discussed their ongoing projects of placing or maintaining monuments and historical markers at old skirmish sites or rumored grave sites. I did not feel at all comfortable with the clannish, secret-handshake vibe and never went again. But I look back now and say, Oh my God! I attended an SCV meeting! Good old progressive, liberal me.

It is startling to me to come to terms with the fact that I am not where I thought I was on the racial-awareness spectrum.

Jimmy Hair

Charlotte, N.C.

“Confederate history is family history, history as eulogy, in which loyalty takes precedence over truth,” Clint Smith writes. Perhaps the Sons of Confederate Veterans should consider this advice from Voltaire: “We owe respect to the living; to the dead we owe only truth.”

George Kovac

Miami, Fla.

My great-great-great-grandfather’s second cousin was a Confederate general. I don’t loathe him. He did what was expected of him in his time. But I would be embarrassed to honor him at his grave site.

Richard Sibley

Phoenix, Ariz.

I was raised as a first-generation Cuban American in Miami in the 1960s and ’70s, with limited exposure to southern Confederate history. I moved to Jacksonville, Florida, in 1994 and within a few years visited the Olustee Battlefield Historic State Park to witness a reenactment of the 1864 conflict where the Confederacy defeated the Union soldiers. I will never forget sitting in the bleachers with my then-5-year-old son and his best friend, who were not particularly interested in watching all these men in wool uniforms strutting about with bayonets amid cannon fire. There were two white men in their 50s near us, passionately discussing how, if General Robert E. Lee had done this maneuver or conducted that battle differently, “we could have won the war.” I was in total shock to realize that, more than 130 years after the horrific Civil War, there were still Southerners (white, of course) who tried to envision another outcome. I left that battle reenactment in disgust.

We still have a ways to go to right the wrongs of this mythology.

Leo Alonso

Jacksonville, Fla.

More than 20 years ago my family went to Charleston, South Carolina. We saw a brochure for Middleton Place plantation and thought it might be instructive to see how a working plantation, well, worked. The grounds were immaculate and the guides enthusiastic.

It became too much as we were being shown the gorgeous back lawn leading down to the river. I looked to our guide for more information. With a smile she said, “It took 100 slaves 10 years to do this work!”

I will never look at a beautiful plantation again without wondering in anger and sadness who built the home, who planted and tended the garden, who wept at night over the forced labor, and who made southern life possible by being brutalized daily. I look forward to visiting the Whitney Plantation with my eyes and heart open to listen to the stories told there.

James A. Gibson

Pittsburgh, Pa.

Clint Smith replies:

I’m so appreciative of the letters and emails I’ve received in response to “The War on Nostalgia.” The article is adapted from my new book, How the Word Is Passed, in which I explore how different historical sites reckon with or fail to reckon with their relationship to slavery. Sometimes, an article or a book arrives in a moment when the topic you’ve explored for years is a central part of the public discourse. Today, we are having a national conversation about how we should study, remember, and account for the shameful parts of this country’s history. Many people are asking: How different might our country look if all of us, collectively, understood the full truth of what has happened here? I hope that this story, and my book, can continue to help those attempting to make sense of this question and others like it.

Behind the Cover

In this month’s cover story, Jennifer Senior looks back on a national tragedy through the lens of one family’s loss. After Bobby McIlvaine was killed on 9/11, at 26, police returned his debris-covered wallet to his father, who kept it sealed in a biohazard bag. The wallet is a symbol of an individual life cut short, and a stand-in for the enduring grief of thousands of families who, like the McIlvaines, are still struggling to make sense of what happened that day.

Luise Strauss, Director of Photography

Christine Walsh, Contributing Photo Editor

The Facts

What we learned fact-checking this issue

In 2011, a collapsing storefront in Money, Mississippi, became the first stop on the state’s Freedom Trail, which commemorates civil-rights history. A sign was unveiled outside the former Bryant’s Grocery, where, in 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Till whistled at a white woman; later, he was murdered by the woman’s husband and his accomplices. In the right-hand corner of the sign was a quotation attributed to Rosa Parks: “I thought of Emmett Till and when the bus driver ordered me to move to the back, I just couldn’t move.” This oft-cited quotation lent credence to the idea that Till’s murder sparked the civil-rights movement. Six years later, however, the quotation was removed from the sign because its origin could not be determined.

There seems to be no record of Parks uttering these exact words. But historical evidence suggests that Till’s murder was on her mind when she refused to give up her seat on the bus, as Wright Thompson notes in his article about Till. According to the scholar Dave Tell, the idea can be traced back to the 2003 book Death of Innocence, by Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley. She describes meeting the activist for the first time in 1988: “Rosa Parks would tell me how she felt about Emmett, how she had thought about him on that fateful day when she took that historic stand by keeping her seat.” Others, including the Reverend Jesse Jackson, have since noted that Parks privately told them the same thing.

Stephanie Hayes, Deputy Research Chief

Corrections

“Bust the Police Unions” (July/August) misstated the duration of the video showing George Floyd’s death. The article also incorrectly stated that George Wallace sought the Democratic presidential nomination in 1968. In fact, Wallace ran as a third-party candidate that year. “Can Bollywood Survive Modi?” (July/August) misstated the nationality of a suicide bomber in Kashmir. Though a Pakistan-based extremist group claimed responsibility for the attack, the bomber was not Pakistani.

This article appears in the September 2021 print edition with the headline “The Commons.”