Brooklyn Funk Essentials’ debut album Cool And Steady And Easy - the album that defined the acid jazz movement - is 30 years old. And to mark the occasion, the band has put together a single, re-recording and reimagining Blow Your Brains out and Brooklyn Recycles, with the BFE live band that’s still touring today.

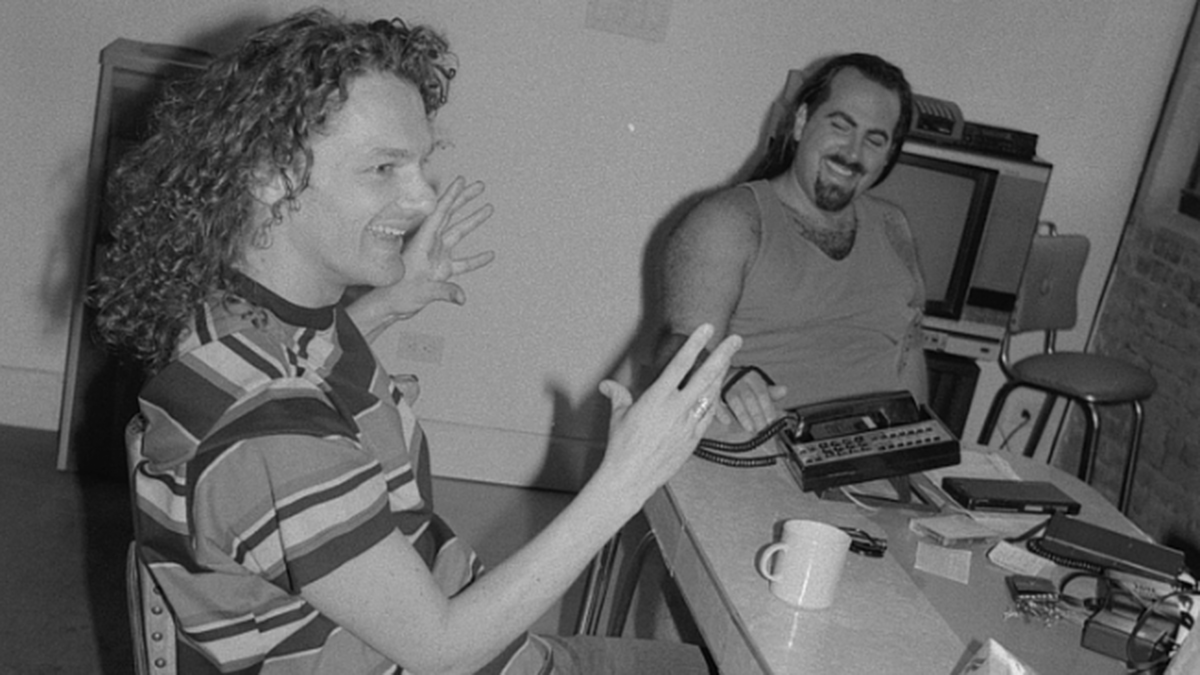

To get the story of the album and find out more about his role in launching both hip hop AND house music into the world, we spoke with legendary producer Arthur Baker and BFE collaborator, writer and producer Lati Kronlund - the creator of house anthem Where Love Lives with BFE vocalist Alison Limerick.

We caught up with Baker, busy working on sessions in Miami and Kronlund, in his studio, in Stockholm to discover why, 30 years later, Cool And Steady And Easy is still such a revered classic.

Cool And Steady And Easy is one of those old favourites that fans keep coming back to. What was the vibe 30 years ago? What was the intention behind getting together and making that album?

Arthur Baker: “Well, we were sort of working on other things. I heard Where Love Lives, which Lati wrote and produced, and I really liked it. I called my friend Mike Sefton who was Lati's publisher at the time. He connected us and we became friends and started working together.

“And at the time I was moving to London a lot and Lati was moving to New York. So we sort of swapped. I had some samples I had been working on - a few things I thought could work - and I played things to Lati and we went from there. It was just experimenting before it became a real thing.

Lati Kronlund: “We started working on it sort of by accident because Arthur was producing an album by Al Green and I was helping him out. I was programming some beats for that and we were supposed to do a guitar session which suddenly didn't happen. And Arthur is not the kind of person who will call the day off - he will find something else to do.

“So he went into his tape cabinet and he came out with a pile of two inch tapes with stuff by Maceo Parker and Tower of Power, all kinds of stuff. And he was like, ‘Hey, maybe we can find some cool samples on this and make a club record’.

AB: “Because at that point that whole groove collective was starting to happen already, right?”

LK: I think that's how it came together and eventually we started to invite people to come and add live instruments onto the stuff that we had. Because what we did in the studio initially was kind of in a hip-hop fashion, you know? With a sampler and drum machines and stuff.

“But then we decided to add singers and players and then when we started to play it to people, everybody was like, ‘This is fantastic. When do you have your next gig?’ And we were like, ‘Gig?’

“It was like somebody asking me to put a band together in New York. It was a dream come true.”

It's such a New York album. From Take the L train onwards it really is a beautiful time capsule of the city.

LK: “One of the first songs we did was from a sample that Arthur found which had to do with New York. We weren't trying to make a New York-themed record, but when we had a list of songs, it was like, ‘Wait a minute, all of these songs are about New York.’ So I guess you're probably right. I was super inspired by being in New York. I’d lived in London for nine years so it was really inspiring and refreshing to come to New York and meet all these people.

AB: “It was just experimenting, writing and playing around. When you have a studio and all the equipment and literally all these tapes… Like the Tower of Power Horn thing that I had was basically from ‘85 so it was seven or eight years old. And the Maceo Parker thing was from a Criminal Element Orchestra album that I did.

“So I had these things hanging around and I thought, ‘I’ve paid for them. Why not use them?’”

What kind of gear were you using for sampling back then?

LK: “It was an S1000. The old Akai. In fact, when I moved from London to New York, I had one black square bag which had my sampler and a thing that you saved the samples on. That was the one thing that I was carrying. That was it.

“And as soon as I got to New York, I went to Sam Ash and bought a new Atari computer with C-Lab Creator.”

And you’d recorded Maceo Parker already?

AB: That was on multitrack - a track from the Criminal Element orchestra record. The Maceo stuff was on 24-track and we just used that performance.”

LK: “We listened to the whole thing and there was one section which we both felt could be structured as a melody. So we sampled that and we didn't change the pitch of it so that we could mix that in with the solo.

“Once we had the melody we programmed a beat around that melody then we brought that back to the solo, which was running live on tape. It was so much more complicated back in those days. When you were combining tape and that old computer… You couldn't record anything into the computer and anything that you did want to record, you had to sample it and the sampler only recorded X amount of seconds. So then you have to chop it up and play it from a keyboard… It was a lot of work.”

That's amazing, that all that gold was left over from another project.

AB: “Well, you have to do two or three takes and then you take it from there. I comped a bit of it. But you always have people overplay.”

LK: “Because that worked so well on that first track, we did the same thing when we brought Paul Shapiro in. He played soprano sax on a track that we had produced mainly from samples from Arthur's record collection.

“And then we did the same thing. We were like, ‘This bit here is really good. This could be a melody.’ So we would sample that section and in that case we had Paul right there so he could replay it or could harmonise to it.

“But it was that way of using the creativity of somebody who could really play and then to bring it into a hip-hop world where you sample it. At the time that was really fresh.”

And how about the involvement of guys like Doug Wimbush and Keith Leblanc? Did that come later or were they samples too?

AB: “Anything of them would have been samples. They didn’t come in and do things for the record. I was working with them a lot, and I had them on those tracks already.”

LK: “The Doug Wimbush stuff, the very treated slap bass that comes in in the bridges? That’s Doug. We sampled that and threw it in with the track.

“But everything else we redid and we brought other people in. Especially like the people from Groove Collective who then became members of Brooklyn Funk Essentials as well. Which got a little complicated because we would have gigs on the same night!”

Given your back catalogue to this point, Arthur, the album was an amazing switch in styles. A very fluid switch from one genre to another.

AB: “Well, I had always been into jazz but it wasn't anything that I really thought about making. I had done A Love Supreme with Will Downing and the track on the album Creator Has a Master Plan kinda came out of that same sort of space in my head. I had already done Creator Has a Master Plan as more of a housey thing but when we started the Brooklyn Funk Essentials project, Lati basically redid it in a whole other vibe. A totally different arrangement, just using the idea of that song.

“Interestingly enough, both songs I did as covers of jazz records both did well. A Love Supreme did really well for Will and Creator Has a Master Plan did really well for us. Makes me think I should, I should have done a few more! Maybe a Miles [Davis] track. Is there a Miles track we could put a vocal to?”

Tell us about the recent re-recording and reworkings. Obviously they’re out to mark the album’s 30th anniversary.

LK: “We did several songs, because the band is still very active and we play a lot of the songs from Cool And Steady And Easy. We also re-recorded Take The L Train. We re-recorded Creator Has a Master Plan, and a few other songs. But we decided to do these partly because Blow Your Brains Out was really the first track we did. So it really felt like the beginning of the whole project.

“The thing that I think is really cute about the re-release is that the new version is completely live. There's nothing programmed on it. I thought it would be fun to make the song in a version as if it was an original ‘70s funk song. That's always where I'm coming from.”

What is it about this particular music that you think holds up so well 30 years later?

AB: “Well, come on. It’s good music! I think great music - unless it's really gimmicky and unfortunately some of the stuff I’ve made has a strong gimmick - wasn't made to be anything really trendy. This was made to be good music with good performances.

“So I think that kind of thing just sort of lasts forever. This was really good music and good music lives on.”

I was working with Joe Bataan on a disco album. We were collaborating. And this was like ‘78 so I was 22 years old and one day he said ‘Bro, you gotta come up to the Bronx. There are these guys and they’re talking over records’.

You were there right there at the start of both hip-hop and house. Did you think that there'd be hip-hop and house 30, 40 years later?

AB: “Well, for me, we never expected hip hop to be around forever. The same with house music. When you're in the midst of it you don't really think of it in those terms. You’re just making this music and you enjoy it while it's happening.

“When I talk to people now and how people are so into commerciality and making money on their music and that's what drives people. But back when we were making this music, the last thing we were thinking about was making money.

“I mean, later on when I was doing remixes and I could grab 20 grand for a remix from the Rolling Stones, yeah, of course. But when we first got into it the mindset wasn't that we're making this to become famous and to make money.

“Even the rappers. They wanted to be able to have their friends hear their records and play them in the club or at the party. Money never came into our minds when we were making the music.”

What was your first brush with hip-hop back in the day?

AB: “I was working with Joe Bataan on a disco album. We were collaborating. And this was like ‘78 so I was 22 years old and one day he said ‘Bro, you gotta come up to the Bronx. There are these guys and they’re talking over records’. They're playing boom boxes and they're talking over records. And I go, ‘What is that?’ And he says ‘You gotta come right now’. And I was in Brooklyn so to go from Brooklyn to uptown to the Bronx was a pretty long trip and I was like, ‘Are you sure?’ And he says ‘No, you gotta come.’

“So I went, I met up with him and there was a guy rapping over Got To Be Real by Cheryl Lynn. And Joe says, ‘Someone's gonna make a million dollars on this’. And that was before it was recorded. That was before Rapper’s Delight. And I was, ‘Oh well. That's sort of cool.’

“But Joe went and did Rap-O-Clap-O right away and he had one of the first rap records.”

I guess the advent of machines like the 808 really kind of defined it as a genre in its own right.

AB: “Yeah, exactly. It broke it away from that live disco sound. Once people had drum machines it became drum machines and live playing. And then drum machines and sequencers. And then drum machines and samplers.

“When we did Planet Rock, there were no samplers. The sampler didn't come until later. You had like a second or two, and a delay unit had a second or two. When I did Renegades of Funk in ‘84, that's when the Emulator came out and that's when we were able to sample. That was the first record I did that was truly a sample record.

“And then all the other machines came out - the drum machines and the sequencers and everything. But ‘84. That was the start of all that.”

How did you get together with Afrika Bambaataa for Planet Rock? What was it like coming up with that?

AB: “My first rap record was with Tom Silverman [founder of Tommy Boy Records] and me going in with Afrika Bambaataa, and we did Jazzy Sensation. I was probably one of the only producers he knew because I was writing for his Dance Music Report. He said, ‘Listen, I got this guy Afrika Bambaataa. He has all these rap groups. You wanna produce?’ That was still at the time when you had to go in and record with a live band live and have them cover another track.

“In the beginning, rap was all about covering disco tracks. Getting the groove, the instrumental and then having guys rap over it. That was it until pretty much until Planet Rock.

“There were no samplers yet. There was some drum machine. It all came out of disco, you know? Disco and funk.”

“And first I did Jazzy Five and that did well. It sold like 50-60-thousand. Which was a lot at the time. And then Tom said, ‘Bam’s got another group’ and that was Soul Sonic Force and Planet Rock.”

So where did the Kraftwerk sample come from?

AB: “Bam and Tom had made a demo of the track with Trans Europe Express on it. I didn't particularly like the demo. But I liked the idea. And then I was in a record shop, Music Factory in Brooklyn, and Dwight, who was one of the managers, played Kraftwerk’s Numbers and I was like, ‘Whoa!’. That’s the beat for it.

“So we married the two of them together and the rest is history, I guess. Obviously, I knew Trans Europe Express for years because it had been out for probably four years. As a DJ that track would get played. And when I first moved to New York I'd hear it played on boom boxes in the Bronx. But it was Bam. He wanted to do it.

“He brought that melody and the claps on the original. And then when I heard Numbers it became a whole other thing. The other beat that Bambataa wanted to use was Super Sporm by Captain Sky.

“John Robie played the keys and stuff. None of us had really worked together in the studio before and it was just sort of magic. So yeah, it was a combination of a lot of people to make that record.”

It’s one of the first tracks where there's such a direct lift from another record. Was that ever a concern? Were you ever worried: ‘What are Kraftwerk gonna think?’

AB: “I mean, before that there was Rapper's Delight. That's what rap was - taking original songs and redoing them. When we did Jazzy Sensation. That was from [Gwen McCrae] Funky Sensation. We re-recorded it, but we gave Gwen McCrae most of the song [royalties].

“So when we did Planet Rock we weren’t worried about the beat. We were worried about the melody. To the extent that I had John Robie play another melody. But we used that on Play At Your Own Risk instead. So we got to use that on another record.

“But the record was so strong - it really needed the melody of Trans Europe Express. As to whether the record would have been such a hit if we hadn’t used Trans Europe Express, we’ll never know.

“But we weren’t super worried about it. Tom paid off Kraftwerk and just upped the list price of the record. So the consumer paid Kraftwerk.”

And then you were there for the birth of house, too. What defined house music for you? If hip-hop was ‘talking over records’, what was house?

AB: “I always said that house was just disco on a budget, basically. The guys were trying to make disco records and they were limited to the technology they had and their ability to actually play. Most of them couldn't play.

“House really came out of electro. People don’t talk about that. A lot of guys in Chicago say that John Rocca, I Want It To Be Real, which came out at the end of ‘83, beginning of ‘84, was the first house record. All those other house records came out in ‘86 but John had that bassline. I wasn’t involved in the production of that at all. He sent that to me for a remix for Streetwise [Baker’s label] and just hoped that I didn’t fuck it up because when I first heard that I was like, ‘Wow, this is really new.””

And then you made I.O.U with John and Freeez.

AB: From that to I.O.U isn’t far. The bassline and the programming on that is what would, pretty much, become house music. The whole ethos of house music - of having a drum machine and playing on top - definitely came out of the electro era which was only a year or two earlier. So it isn't a mystery to figure out how things happened.

“John doesn’t get enough credit for that record. But put it this way. Farley Jackmaster Funk heard that record and he came to stay with me and John was staying in my basement in New York, and they did a whole John Rocca album. He was that into John, he came from Chicago, to produce him.

“I think house music came out of people not having much money and so they made the records in their homes and mixed them down to cassettes.”

I think I.O.U was the first time I ever heard a sample. The sampling of John Rocca saying A, E, I, O, U…

AB: “And that was Jellybean Benitez’ idea. He was like, ‘Can’t we sample all the vowels?… And then Robie, you can play them on the Emulator as a solo?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, let’s do it.’ But it was Jellybean’s idea. It’s such a great hook.”

And John Rocca is an English guy. How did you guys first work together?

AB: “Well, Freeez had just had that song Southern Freeez, which was a hit. And they wanted to work with me and they sent me stuff and then they just showed up one day at my office at Streetwise. They literally showed up without me having committed to them or anything. And I basically felt bad for them!

“So I did the album. We didn't use anything that they had showed up with. I just said, ‘Let's write the album together’ and I.O.U was the last track. I was like, ‘We don’t have a hit’ but that came into my head and I said, ‘OK, let’s finish it.’”

So when you were creating I.O.U did you know you were creating the bridge between hip-hop, electro and house?

AB: “Nah, I just thought it was a hit. I had total 100% confidence when it was done that it would be a big hit. You basically just know.”

And Lati, does the same go for when you came up with Where Love Lives?

LK: “I still remember the night I came up with that piano riff. I was like ‘Shit…’. I was playing it for three hours. I was like ‘Yes!’”

AB: “Yeah, I think when you do a track like that, I mean, you know. When we did Creator Has A Masterplan that sounded like a hit to me too. And when A Love Supreme when that was done, I was like, ‘Wow, that's magic.’”

LK: “When I wrote Where Love Lives, it was because I had seen Ten City at the Dominion Theatre in London and I was blown away. I loved them already, I had the album but when I saw them, I was just like, ‘This is the shit’. They were like The Undisputed Truth… but with a house beat. So the music had a lot of roots in the seventies, disco and funk.

AB: “You know Norman Whitfield [Motown psychedelic soul legend] is a guy that’s totally slept on. He's the guy. All this stuff comes from him. The basslines, everything.”

Was Where Love Lives always written for Alison Limerick?

LK: Actually I was working with Claudia Fontaine, from Soul II Soul. And we recorded a series of demos and I played her Where Love Lives and she was like, ‘No, I'm not doing house music… I think it's a nice song… but I'm not doing house music’. So I was like, ‘OK, it's fine’.

“And then I went to this party where Alison was doing a fashion show at the ICA in London and singing God Bless The Child sitting on a swing… And was like, ‘There’s my girl’. So I went up to her afterwards and I asked her, ‘Do you wanna sing a song? I've written a song’. And she was like, ‘Alright’. I'm so happy that Claudia didn't want to do it because Alison’s the right one for it.”

How much of that track is programmed and how much is played? Are you playing the piano on that?

LK: “The version that's on the album. That's me playing pretty much everything. But obviously, Frankie [Knuckles] and David [Morales]'s remix is done in New York but Frankie used musicians too. He didn’t just program. All those little synth lines. They were played.

AB: “A lot of the best music around that time, the drums would be programmed but there was a lot of live playing on top. When I was starting with drum machines, I'd always specifically want a piano, and live synths played on top. That gave it more of a live feel, even when it had the drums programmed.

“Like Rocker’s Revenge. Walking on Sunshine. Programmed drums. Everything else: live.”

Traditionally people attribute genres and music changing through the creation of new technology.

AB: “Yeah, totally true. I totally believe that. Without the electronics there wouldn't have been techno or house. Because house without a drum machine is disco. What made it house music was drum machines and programming.”

Without the electronics there wouldn't have been techno or house. Because house without a drum machine is disco. What made it house music was drum machines and programming.

And what was the next big breakthrough in technology for you? And what did that allow?

AB: “Well, when it started going all digital. A lot of the tracks we did to tape, I still have. But tracks that were done digitally… Sometimes we’d lay them down to ADAT and some just got lost. We weren’t saving stems, like you do now. But we weren’t really thinking. That the program we were using wouldn’t be available in 15, 20 years time! Looking back, the fact that we didn’t save the stems is kinda crazy.”

What’s next from you guys? There’s the new single out with the re-records. Anything else coming out with the Brooklyn Funk Essentials name on it?

LK: “Well we may release some of the other re-records. But it's really just a tribute thing, you know?

“We're still touring through the summer and we have a few more gigs lined up, but then we're gonna start recording new stuff. And we're hoping that we'll have a new album by next summer.

AB: “I just put out this compilation through Soul Jazz Records in the UK called Breaker’s Revenge. It's sort of a B-boy classic compilation with Give It Up Or Turnit A Loose, It’s Just Begun, Scorpio… A lot of the classics plus some more obscure tracks and Planet Rock and Breaker’s Revenge are on it.

“And then I’m putting together the Beat Street boxset for the 40th anniversary. That won't be until the beginning of next year. But I’m making records, too. I’m doing a live rumba Latin record that I cut live in Miami, which is really cool. That’s with Jose Parla who is a contemporary artist. He started out as a graffiti artist, but he's very really successful. His art goes for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

“And I’ve directed a film about Rocker's Revenge which tells the story of the group which should also be out next year.

“And I’ve finished my book! Yeah, I've written my memoirs. It's meant to be out next year around April. I did it with Faber and Faber and it's pretty much done. Other than the final chapter, which is obviously a difficult one because I'm still doing a lot of stuff. So I gotta tie it up.

“And Lati, I’ll send you some stuff! I want to make something that when I DJ, I play it and people go nuts! I mean, that's what I gotta be.”