A quiet surprise of the 86th Legislature was the failure of many of the Christian right’s priorities. While lawmakers closely aligned with religious conservatism proposed several measures to enable religion-based discrimination, further blur the line between church and state and attack abortion rights, few of those bills made it to the governor’s desk. And the ones that did were weak or symbolic.

Disgruntled Christian right activists are now accusing GOP lawmakers of ditching the conservative agenda. But it’s also possible that religious conservatives ran up against the limits of their power, which appears to be ebbing in post-2018 Texas.

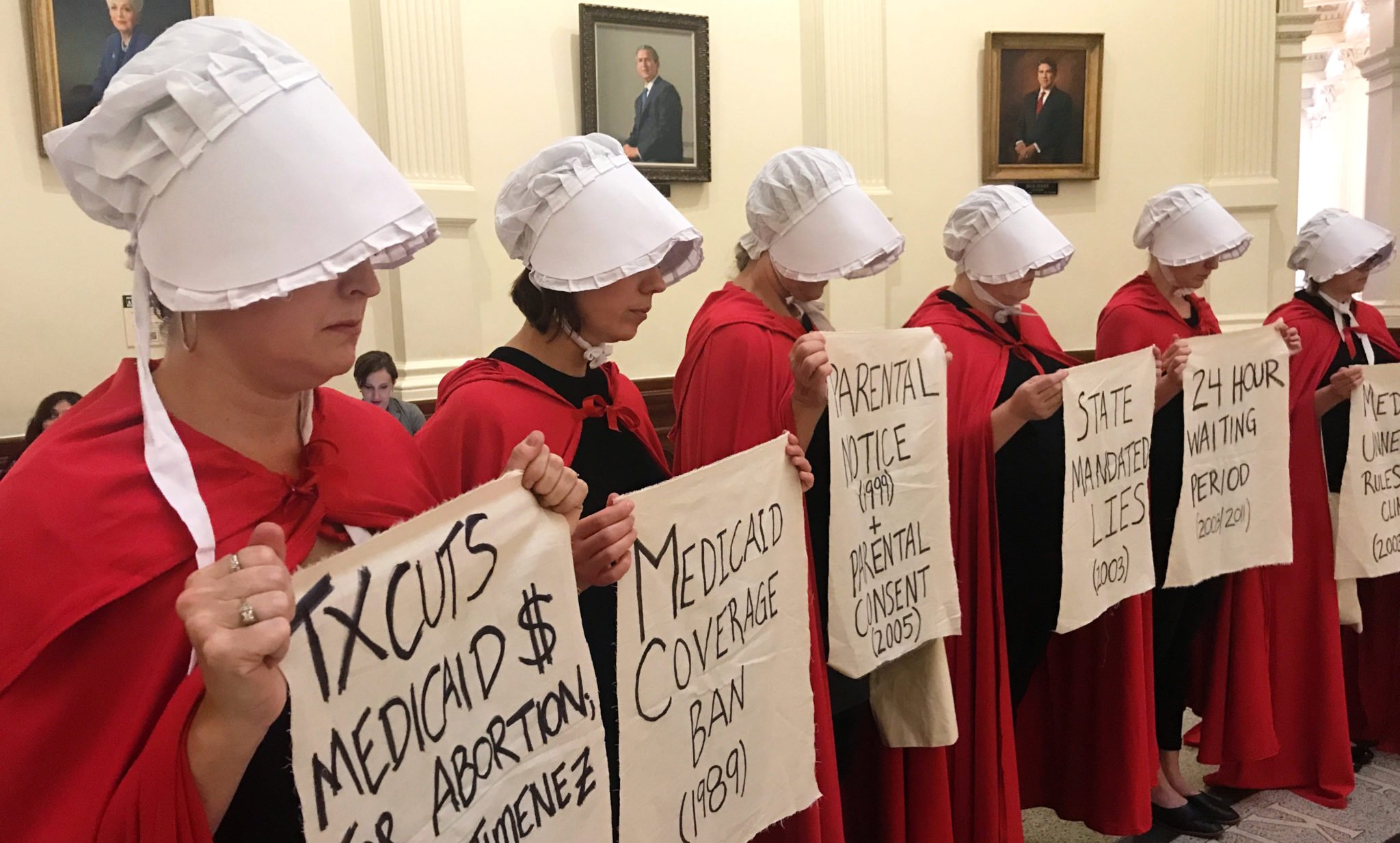

Christian conservatives have enjoyed plenty of legislative success under a Republican-controlled Legislature. Since 1995, the Legislature has mandated that public school health education stress sexual abstinence and prohibits teachers from distributing condoms. A decade ago, it began allowing public high schools to offer an elective course on the Bible. The religious right helped push through one of the toughest abortion laws in the country in 2013. And while last session’s bathroom bill didn’t pass, religious conservatives still scored substantial wins in 2017: another omnibus anti-abortion law and one that allows child placement organizations to refuse on religious grounds to place children with certain parents, such as LGBTQ and non-Christian couples.

But this year was different. Christian conservatives had little success on the so-called religious liberty front, despite their new “#BanTheBible” message. Their one win, the much-ballyhooed “Save Chick-fil-A” bill, was substantially softened — language about “sincerely held religious belief or moral conviction” gave way to the more ambiguous affiliation with “a religious organization” — in order to pass the House (though critics contend it still achieves its goal of undermining LGBTQ rights.)

But more far-reaching measures bit the dust. SB 17, a priority for Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick and other religious conservatives, would have shielded state-licensed professionals who discriminate on religious grounds. It passed Patrick’s Senate, but died without much fanfare in the House. One of the biggest priorities of the session for Republicans, SB 15, an anti-labor bill that would have preempted paid sick leave and other employee protections, died because of the religious right’s push to attach anti-LGBTQ provisions.

Attempts to chip away at the separation of church and state, a perennial Christian right priority, made no headway this session. Bills that perished include: one allowing the posting of the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms; another requiring that “In God We Trust” be displayed in government and public school buildings; and legislation mandating that the State Board of Education add instruction about the Bible to the English language arts curriculum in public schools.

As states like Alabama and Missouri enacted sweeping abortion bans, similarly stringent measures in Texas failed this session. Those include an effort to criminalize all abortion, the so-called fetal heartbeat ban and a measure that would have prohibited abortions where the pregnancy isn’t viable or in cases of severe fetal abnormalities.

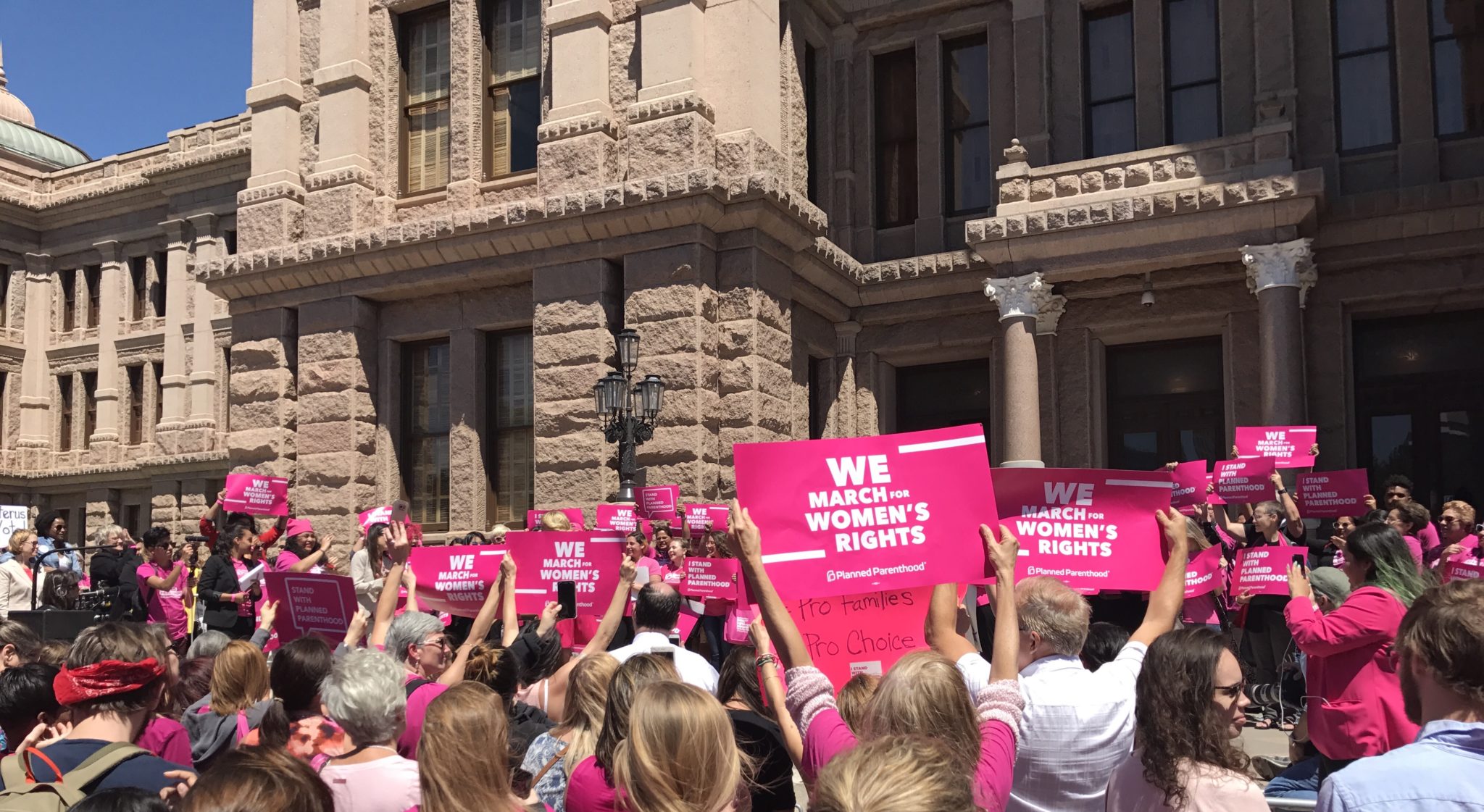

The small victories anti-abortion groups achieved were largely symbolic. HB 16, for example, fines physicians who fail to care for an infant born alive after an abortion, but such cases are vanishingly rare and are already covered by federal law. SB 22, the latest missive in the Christian right’s ongoing vendetta against Planned Parenthood, only deals with preventive reproductive health care. And SB 24, which mandates that women seeking abortions receive state-supplied information about adoption and “the characteristics of an unborn child,” does nothing to actually stop abortion.

Those meager gains have left social conservatives crying foul. Legislators “shirk[ed] their responsibility to protect life” and passed “feel-good,” “optics-only” bills, charges Texas Right to Life. Former state Senator Konni Burton’s The Texan complains of “a public rift between lawmakers and activist organizations” on abortion issues. And North Texas Tea Party leader Julie White McCarty was even more blunt: “We got nothing,” she said.

So what happened?

For one, the 2018 midterms. Democrats knocked off 12 House Republicans and came close enough to scare others into significantly moderating their politics. They also picked up two state Senate seats, weakening Patrick’s hand in the social conservative upper chamber.

“The pitchfork crowds of angry voters in 2018 … were looking for lawmakers who would make progress instead of noise in Austin,” Brandon Rottinghaus, a political science professor at the University of Houston, told the Observer. “The 2018 results spooked many Republican members that the course they were on was creating political damage and repelling as many voters as it attracted.”

But it wasn’t just one election. There are bigger trends at play. While evangelicals remain the state’s largest religious group, the share of religiously unaffiliated — atheists, agnostics and those who don’t belong to any particular religion — is on the rise. One in five Texans are religiously unaffiliated, and about a third of them are under 30. Nationwide, the unaffiliated population grew by almost 7 percent between 2007 and 2014, while Christians declined by nearly 8 percent.

As Elizabeth Oldmixon, American politics professor at the University of North Texas, told the Observer, “The Christian right in Texas is playing on their home field, but the games are certainly more competitive than they used to be.”

Editor’s note: This story initially reported that a 2007 state law requires Texas public schools to offer an elective course on the Bible. In fact, the law provides schools with the option but does not mandate them to offer the course.