An HIV diagnosis hasn't been a death sentence for years, thanks to powerful medications.

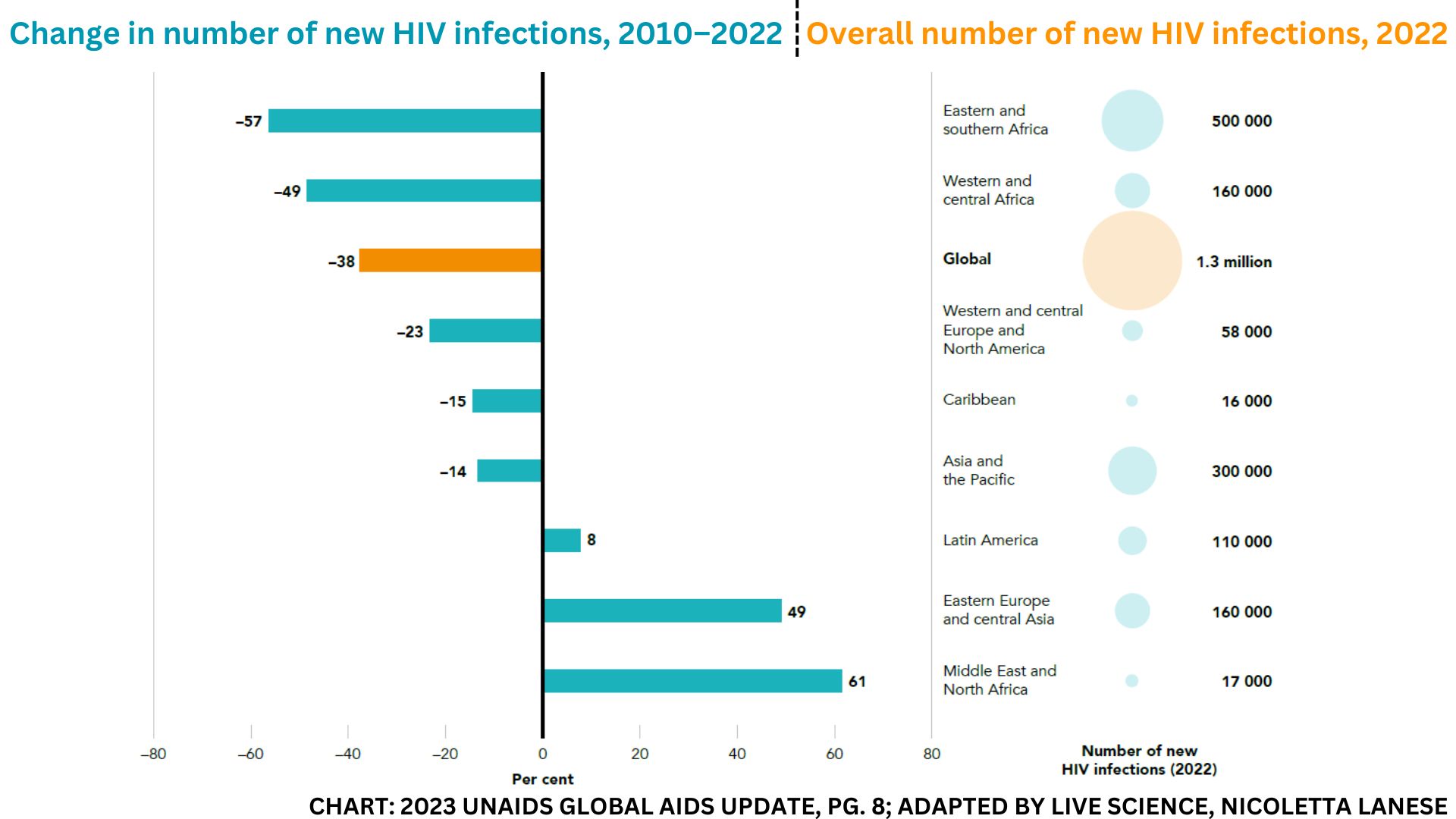

Despite incredible progress, however, HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) remains a global public health threat, with 1.3 million new infections and around half that many deaths in 2022 alone.

While new HIV infections have dropped steadily since their peak in 1995, as people live longer with the disease, the pool of people who are HIV-positive has only grown. People with HIV must consistently take medications to prevent the virus from becoming transmissible again or progressing to AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). As a result, new infections could actually rebound fast if the world doesn't dramatically ramp up the number of people being regularly treated, tested and protected from new HIV infections.

But we could head off that rebound risk by the end of the decade, experts say.

Countries around the world have signed onto an ambitious United Nations program with a goal to "reduce the rate of new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths to below the reproductive rate of 1," country by country, Quarraisha Abdool Karim, associate scientific director of the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa and a joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) special ambassador, told Live Science. That would mean each person living with HIV would infect fewer than one additional person in their lifetime.

If the program is successful, we'd see 200,000 new HIV infections and 130,000 AIDS-related deaths worldwide in 2030 — 90% fewer than in 2010. While eradicating the virus would require a vaccine and cure, we could eventually drive HIV infections and death rates to near zero without those tools, Abdool Karim said.

"We do have the tools to end AIDS as a public health threat. We do have the biomedical interventions," she said. "The challenge is, how do we all get to that point?"

Related: Could CRISPR cure HIV someday?

From the first treatment to ending AIDS

The first, imperfect HIV treatment, AZT (azidothymidine), was approved in 1987. Nearly four decades and more than 40 million AIDS-related deaths later, we're still hunting for a vaccine and a cure for HIV, but our treatments have dramatically improved.

"We've had really powerful treatments, really, since 1996, but they just get better all the time," Dr. Monica Gandhi, director of the University of California, San Francisco Center for AIDS Research and medical director of the HIV Clinic at San Francisco General Hospital, told Live Science.

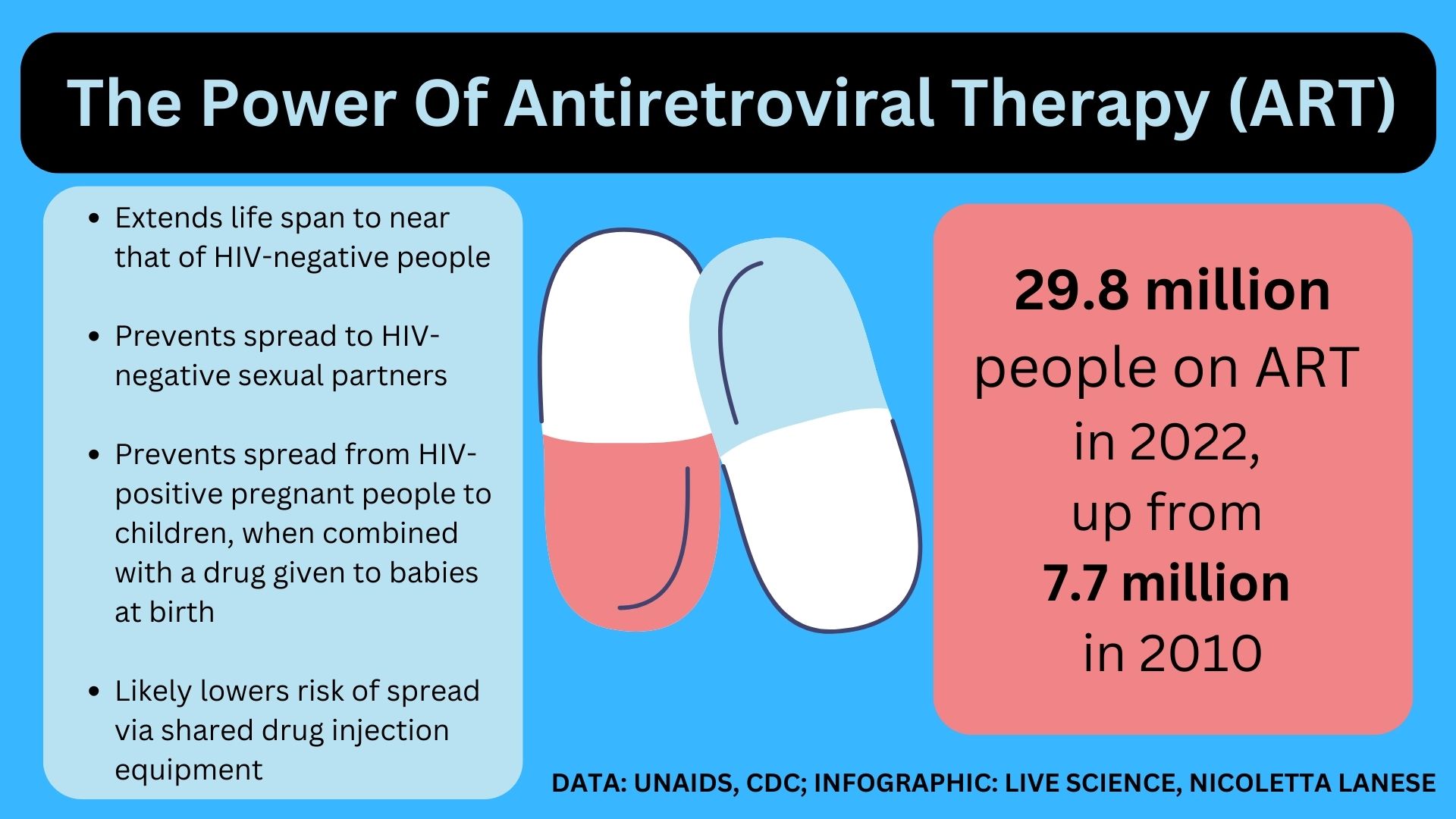

Today's standard treatment, combination antiretroviral therapy (ART), uses several drugs to disrupt HIV's ability to replicate and invade immune cells. Given as daily pills or monthly or bimonthly injections, ART slashes the amount of HIV in a person's blood until it's undetectable. If maintained, "viral suppression" extends a person's life span to about that of HIV-negative people and eliminates their chance of spreading HIV via sex.

"People living with HIV, on treatment and undetectable, are not infectious — full stop, end of statement — to their sexual partners," Dr. Raphael Landovitz, co-director of UCLA's Center for HIV Identification, Prevention, and Treatment Services, told Live Science. Viral suppression also nearly eliminates HIV spread to babies during pregnancy or childbirth, greatly reduces spread via breastfeeding and likely lowers spread from sharing syringes.

We also have powerful medicines that prevent HIV-negative people from contracting the virus if exposed. Known as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), these drugs are available as daily pills. There's also an injectable drug called cabotegravir (brand name Apretude) that's given bimonthly. Some African countries have also licensed a vaginal ring for HIV prevention; it's less effective than PrEP pills but works for a full month. And condom use and voluntary male circumcision also cut transmission.

By 2014, there was strong consensus that the drugs we had could end the AIDS epidemic. But those drugs weren't being rolled out fast enough to head off rebounds in infection, UNAIDS cautioned. At that time, models predicted that if treatment and prevention services didn't reach more people over time, the number of people with HIV would balloon to 41.5 million by 2030. To prevent this, UNAIDS set forth ambitious targets to scale up the global HIV response. Hitting these targets would prevent 28 million new HIV infections and at least 21 million AIDS-related deaths between 2015 and 2030, they projected.

One major goal, the "95-95-95" target, is set for 2025. Achieving it would mean 95% of people with HIV know their status, 95% of those diagnosed take HIV drugs, and 95% of those treated are "virally suppressed," meaning the drugs keep them from spreading the infection via sex. This translates to around 86% of people with HIV being virally suppressed.

Other 2025 targets aim to ensure that 95% of people at risk of HIV have access to prevention and that PrEP be made available to at least 10 million at-risk people.

So far, we're not on target: In 2022, only 76% of the total 39 million people with HIV worldwide were taking ART, and 71% were virally suppressed, according to the latest UNAIDS report.

So what can we do to reach 95% across the board?

Related: How are people cured of HIV? Here's everything you need to know

Vulnerable populations

A big hurdle to ending the AIDS epidemic is getting treatments to vulnerable populations, including children. In 2022, only 57% of the 1.5 million children under 15 with HIV received treatment, 46% were virally suppressed and an estimated 84,000 died of AIDS-related illnesses.

That's partly because kids aren't typically included in initial clinical trials for treatments, so there are relatively few child-friendly formulas, Abdool Karim said. The preferred treatment for children, a tablet that dissolves in water, was just approved in 2021 and has been adopted only recently in many countries. However, most other HIV drugs for kids taste bad, are difficult to swallow or must be taken several times a day, UNAIDS notes, so improving these formulations could make their HIV regimens easier to maintain.

Long-acting ART options — meaning those that don't require daily pills — are nonexistent for children under 12, Gandhi said. To help make long-acting ART suitable for young children, the National Institutes of Health is supporting research into how to best adapt drugs approved for adults, she noted. But that grant opens in 2024, so it's unclear if it could make a dent before 2030.

And even if better drugs are widely available, "children are not going to be able to access antiretroviral therapy in a vacuum," said Dr. Anjali Sharma, a professor of medicine who now studies complications of HIV at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York and has studied ART adherence in different settings.

"The pediatric care really has to be integrated with other services, potentially the mom's treatment or things that are going to work with the family as a unit," she said.

The science is a first step, but access is what will translate its true potential and value.

Quarraisha Abdool Karim, CAPRISA

Hitting the 95-95-95 target will also require better reaching teen girls and young women, especially with prevention and testing. Nearly 1 in 6 new HIV cases in 2022 were in girls and women ages 15 to 24, many of whom are in sub-Saharan Africa.

Once diagnosed and started on ART, women's viral suppression rates are "high and so are survival benefits," Abdool Karim said. Among all diagnosed women over 15, 82% had access to ART and 76% were virally suppressed in 2022. But starting ART first requires being tested for HIV, and testing rates remain low in hard-hit regions, particularly among teens.

Many of the hardest-hit regions lack prevention programs for young women, and the few existing programs often miss girls who are not in school. Girls facing a lack of education, poverty and food insecurity have an especially high risk of HIV, as do girls with older male partners. Intimate-partner violence and sexual coercion often mean they cannot control when they are exposed to HIV. Plus, in some countries, HIV services require parental consent, which can also reduce girls' access to prevention and treatment.

Improving girls' access to discreet prevention services as well as sex education — both in and out of school — will be key to reducing their HIV rates. Cabotegravir, which is "stunningly effective against vaginal acquisition of HIV," could be a powerful tool for HIV prevention in women, Landovitz said.

Other populations that are far from the targets include transgender people with HIV, an estimated 44% of whom are on ART, and HIV-positive men who have sex with men, who have 78% ART coverage. In addition, just 65% of HIV-positive sex workers and 69% of HIV-positive people who inject drugs take ART. Compared with the general adult population, these groups have far higher HIV prevalence, ranging from fourfold greater among sex workers to 14-fold greater among transgender people.

And those numbers could be an undercount, as many countries don't track these populations. Punitive laws, police harassment, harsh stigma and social taboos keep many people out of HIV care, while high rates of incarceration and sexual violence also raise their risk of acquiring HIV. Lifting discriminatory policies and weaving HIV care into trusted, community-based programs will be key to reaching these demographics.

Related: Patient's immune system 'naturally' cures HIV in the second case of its kind

Cost barriers

The tools to end the epidemic by 2030 will work, but only if they get to the people who need them. "The science is a first step, but access is what will translate its true potential and value," Abdool Karim told Live Science.

For instance, the number of people taking PrEP pills rose more than tenfold from 2019 to 2022. But cabotegravir, a potential game changer, is not yet widely used due to its high cost — $3,700 per dose in the U.S. The drug's nonprofit price will be around $30 a dose, the drug's maker recently told the South African news outlet Bhekisisa, and generic versions will be manufactured in coming years. But the current high price means HIV programs have yet to fold cabotegravir into their budgets, Landovitz said.

"There's still not a drop of cabotegravir to be had anywhere in Africa," where some of the highest rates of new HIV infections occur, Abdool Karim said.

And regardless of the type of ART they take, a patient should have their viral load checked regularly. In 2022, 21 million people underwent routine viral-load testing, up from 6 million in 2015. Viral-load tests are expensive, though, so proxy measures — such as a urine test Gandhi and colleagues designed to track ART levels — could help fulfill the same purpose cheaply.

In addition, an estimated 25% of people stop ART treatment, sometimes for six months or more, often because they face stigma, can't get to the clinic or can't afford treatment. These individuals, many of whom come from vulnerable populations, represent a growing proportion of the AIDS cases seen in hospitals.

"That is preventable and avoidable and really represents a failure on many levels," Sharma told Live Science. "But the failure isn't really the drug itself." It's a failure of the support system that could keep people on ART, she said.

Related: HIV may hide out in brain cells, ready to infect other organs

Success stories and further work

Despite the hurdles, some countries are well on their way to meeting UNAIDS' goals. Botswana, Eswatini, Rwanda, the United Republic of Tanzania and Zimbabwe have already hit the 95-95-95 target set for 2025, and an additional 16 countries are close to reaching these milestones.

The U.S. trails behind. In 2021, 75% of the people diagnosed in the country received "some HIV care," and 66% were virally suppressed. Men who have sex with men made up the highest proportion of new infections in the U.S., with Black, Hispanic and Latino populations predominantly affected.

Countries that have hit the 95-95-95 targets offer universal, free ART access, Landovitz noted, while the U.S. government only has programs to help cover uninsured people's HIV treatment. Racism, homophobia and transphobia often keep people from getting care, he said. And especially in urban centers, people dealing with housing insecurity, substance use and mental health issues struggle to access ART consistently, Gandhi said.

Eastern Europe and Central Asia also lag far behind, with just 51% of people with HIV getting ART and less than half being virally suppressed.

Related: Oldest 'nearly complete' HIV genome found in forgotten tissue sample from 1966

Beyond 2030

We face many obstacles on the road to ending the AIDS epidemic — but we do hold all of the tools to get there, Abdool Karim, Sharma, Gandhi and Landovitz agreed. By using those tools effectively, we could begin to meaningfully drive the number of new HIV infections toward zero. At that point, HIV would become a manageable, chronic disease of the elderly.

Already, about a quarter of people with HIV worldwide, and about half of adults with HIV in Western and Central Europe and North America, are at least 50 years old. "They're growing older with HIV; they're not dying from HIV or AIDS," said Sharma, whose research focuses on aging populations with HIV.

But that doesn't mean the quest for an HIV vaccine or cure is any less important, even if neither is likely to materialize in the next seven years, Abdool Karim said.

"We need to continue our investments to find a vaccine, to find a cure," she told Live Science. "Because that will then say, 'That's it.'"

.jpg?w=600)