He wrote songs that shaped the sound of heavy metal in the early 80s, among them Phantom Of The Opera, Wrathchild, Run To The Hills, The Number Of The Beast and The Trooper. But when Iron Maiden bassist Steve Harris thinks back to the very first song he wrote – in the early 70s, when he was aged just 16 – he can only laugh at the absurdity of it all.

“My first band was called Influence,” he says. “Then we changed the name to Gypsy’s Kiss, which is Cockney rhyming slang for you know what. And I wrote this song that had an awful title: Endless Pit. Which isn’t Cockney rhyming slang, but it should be.”

The title wasn’t his. The blame, he says, falls on his school friend Dave Smith, who wrote the song’s lyrics. But forgetting the title there was something about that song – something that would prove hugely significant in the life of Steve Harris. Later, the main riff in Endless Pit was developed into a new song called Innocent Exile, which Harris performed with Smiler, the band he joined after Gypsy’s Kiss broke up. He also took that song into the band he formed in 1975. The band in which his singular vision would be fully realised, the band he has led ever since.

Innocent Exile was, in essence, the first Iron Maiden song. The first step on the road to world domination for one of the greatest heavy metal bands of all time.

This year, Iron Maiden celebrate their 50th anniversary with the Run For Your Lives tour, in which they will perform classic material from 1980 to 1992.

Ahead of this, Classic Rock met up with the band in New York City in late 2024 during the last weeks of their Future Past tour. The six members of the band – Steve Harris, singer Bruce Dickinson, guitarists Dave Murray, Adrian Smith and Janick Gers, and drummer Nicko McBrain – were interviewed separately over four days, before and after a show in Brooklyn. All spoke at length about the highs and lows of Iron Maiden’s career and their own lives within it: the classic songs and landmark albums; the personal challenges each of them has faced. They discussed the band’s longevity; how they have made it this far, and what the future might look like – for Iron Maiden and for themselves as individuals. As Steve Harris said: “When you start out as a band, you don’t think further than your first album. You dream about touring the world. Anything else is a bonus. So to still be doing that all these years later is incredible. I feel so happy and lucky I can still do it.”

Bruce Dickinson was equally buoyant. “I always wanted this to be the most extraordinary heavy metal band in the world,” he said. “And I think we are, actually. With the repertoire, the songs, the depth…”

With Nicko McBrain there was a slightly different tone, lacking a little of his natural ebullience. He spoke candidly of how, on the Future Past tour, he had experienced difficulties with his dexterity since suffering a stroke in 2023; how he had adapted his approach to playing drums, easing back a little, cutting down the fills in certain songs or omitting them altogether in others. “It’s funny,” he shrugged, “because sometimes when I sit at my practice kit I can do the big drum fill in the intro to The Trooper. But even then it’s a bit flaky, it’s not clean. So rather than do it and not get it right, I leave it out.”

He continued: “I’ve had forty-two years with Iron Maiden. Incredible. But none of us is getting any younger. Who knows how much God is going to grace us with in terms of longevity?”

In retrospect, it seems that he was already resigned to what was to come. Just a few weeks after talking to Classic Rock, McBrain announced on X that the final date of the Future Past tour, in São Paulo, Brazil on December 7, 2024, was his last with Iron Maiden.

Now, the Run For Your Lives tour is more than purely a celebration of Maiden’s 50 years. Simon Dawson, the drummer in Steve Harris’s other band, British Lion, has been installed as McBrain’s replacement. And with this, the band’s first line-up change in 25 years, comes the beginning of yet another new chapter for Iron Maiden.

In late-afternoon sunshine, Steve Harris sits in the back of an SUV moving alongside the glittering Hudson River, en route from Manhattan to Brooklyn. The youngest of his four daughters sits up front. She’s 21. Her father is thinking back to when he was even younger.

He can’t remember the exact date, but it was in late 1975, September or October, when the 19-year-old Steve Harris put the first version of Iron Maiden together. “It was Terry Rance and Dave Sullivan on guitars,” he says, “me on bass, Ron Matthews on drums – we called him Rebel – and Paul Day singing.” Harris decided on the name of the band during the Christmas holiday period. “Even my mum thought it was a great name,” he says, smiling. At the time, he was working as a draughtsman and living with his nan in Leytonstone, East London, after his parents had moved out of the city. “I could walk to the Cart & Horses if I wanted to,” he says of the pub where the band played their first gig, in 1976.

As leader of his own band, Harris was free to create music far removed from the meat-and-potatoes boogie of Smiler. Inspired by heavy rock giants Deep Purple and UFO and the progressive rock of Jethro Tull, King Crimson and Genesis, he quickly developed a unique style of songwriting – illustrated most powerfully in what he says is the definitive early Maiden song: Phantom Of The Opera.

“As a bass player, I don’t write or play like a guitarist would,” he says. “And with Phantom it was obvious that my style of writing was very different to what people were used to, and what guitarists were used to. My songs were unusual, a bit quirky, but it felt natural to me. And I wanted to play with aggression. People said that Maiden had this ‘punk’ thing, but everyone knows I don’t like punk at all, so it’s not that. At that age you’re full of energy, and that’s what you want to come through, but with loads of melody. That’s why I wanted twin guitars.”

There were numerous line-up changes in the first few years: brief periods with a singer, Dennis Wilcock, who fancied himself as the next Alice Cooper; a drummer, Barry Purkis, known as Thunderstick, who wore a balaclava on stage at a time when the IRA and the Yorkshire Ripper were putting the fear of god into people in Britain. But by 1978 Harris’s plan was coming together. He had a trusted second lieutenant in guitarist Dave Murray, whom he had fired a year earlier over a dispute with Wilcock. He’d also found a singer with a powerful voice and presence, Paul Andrews, who dubbed himself Paul Di’Anno.

As the band toured the UK and recorded a first demo tape, a grass-roots scene was developing, the headbangers’ answer to punk, christened The New Wave Of British Heavy Metal by weekly rock magazine Sounds. “We were in the right place at the right time,” says Harris. And in 1979 he found arguably his most important ally in Rod Smallwood, a former booking agent who became Iron Maiden’s manager, the Peter Grant to Harris’s Jimmy Page. It was Smallwood who secured Maiden a deal with major label EMI.

In December 1979 the band’s self-titled debut album was recorded in London with the line-up of Harris, Murray, Di’Anno, drummer Clive Burr (poached from rival band Samson) and second guitarist Dennis Stratton. It remains one of the greatest heavy metal albums ever made, full of electrifying songs, raw energy and streetwise attitude. Arguably the most influential album that came out of the NWOBHM, it was an inspiration for Metallica and many others that followed. And on the album’s cover, illustrated by Derek Riggs, was the monstrous figure of Eddie – an image that would become, in the words of Kiss star Gene Simmons, “the perfect trademark”.

Maiden’s second album, Killers, followed in 1981. It included Innocent Exile, the ground-zero Maiden song. It was the band’s first album with guitarist Adrian Smith, who had replaced Dennis Stratton. It was also their last with Paul Di’Anno.

After his exit from Maiden, Di’Anno had an erratic career and a chaotic lifestyle. In the months leading up to his death from heart failure on October 21, 2024, he had performed gigs while in a wheelchair, and had reconnected with Steve Harris. “I was in touch with him until a couple of weeks before he passed,” Harris says.

After a moment’s pause, he smiles as he remembers the good times they shared. “Paul was a lovable rogue. He liked to annoy me by dressing up like Adam Ant. Anything to wind me up. He liked to ruffle a few feathers, let’s put it that way. And ruffle he did! He used to call me Hitler. I’ve been called the Ayatollah and Sergeant Major, but Hitler takes the biscuit, really.”

After Di’Anno was dismissed from Maiden, he conceded that he only had himself to blame. Too many times he had blown his voice out on the road – too many late nights, too much booze and cocaine.

“Paul’s voice had a certain quality to it,” Harris says. “A rawness. But he didn’t look after himself. He had this self-destruct button. And I got the impression that he never really believed he had it in him to go to the next level. I think there was an insecurity there.”

There was no such insecurity with the singer who replaced Di’Anno. Bruce Dickinson, like Clive Burr, joined Iron Maiden from Samson, and had no doubts about what he had – a voice of phenomenal range and power. The doubts were in Harris’s mind. “I was very worried at having a singer change at that point,” he admits.

But in February 1982, Run To The Hills, Maiden’s first single with Dickinson, hit the UK top 10. An even greater affirmation followed with the album, The Number Of The Beast.

“The fans took to Bruce incredibly well,” Harris says. “It was an absolute relief, if I’m honest. And then the album went to number one, and it’s like: ‘Wow, what’s happening here?’”

Hailed by Sounds writer Garry Bushell as “epic stuff”, characterised by “raging Purplesque mayhem”, The Number Of The Beast was a giant leap forward for Iron Maiden, with Dickinson’s mighty voice at the rarefied level of legends such as Ronnie James Dio and Rob Halford. Over time, The Number Of The Beast would be widely acclaimed as the definitive Maiden album, with deathless heavy metal classics in Run To The Hills, Children Of The Damned, Hallowed Be Thy Name and that hellfire title track.

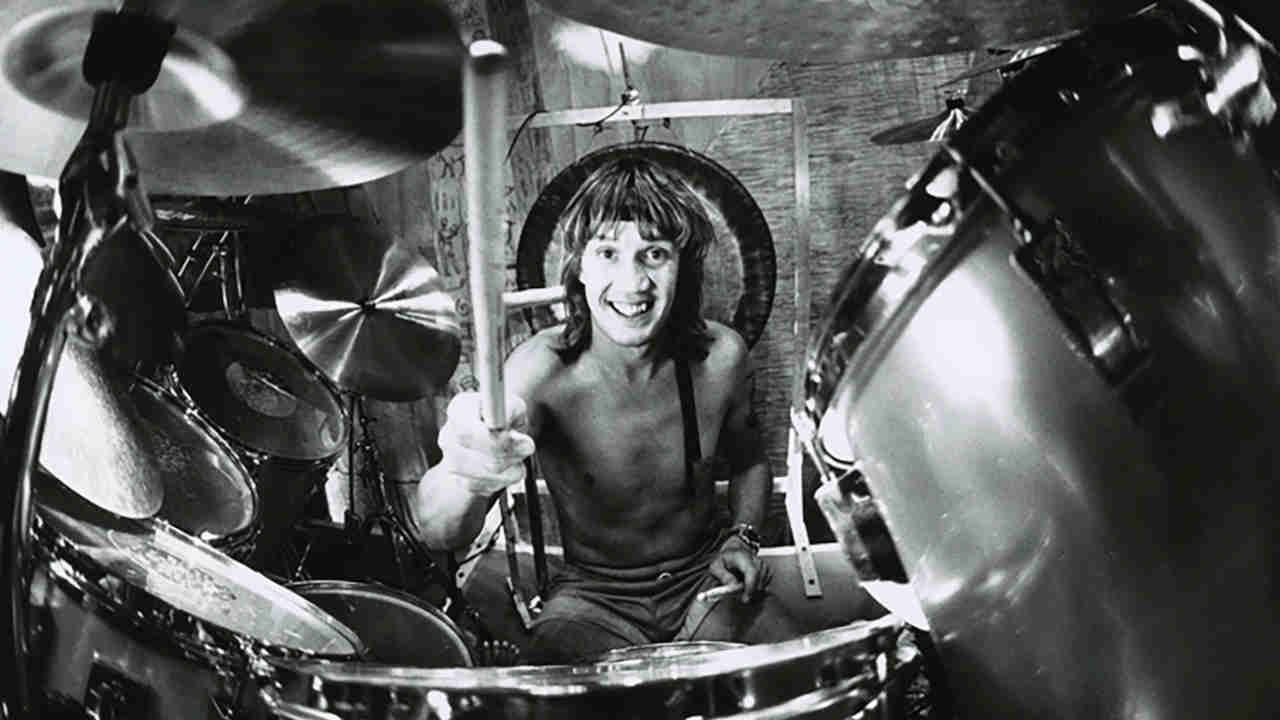

The Beast On The Road tour was Clive Burr’s last with the band. His replacement was Nicko McBrain, who debuted on the 1983 album Piece Of Mind. With this and another monolithic album, Powerslave, Iron Maiden became the world’s leading metal band.

“It was full-on in those years,” Harris says. “Album, tour, album, tour. We got hardly any time off. But it was great. That’s what we wanted.”

However, not everyone in the band wanted it as badly as Harris. In the mid-80s the aptly named World Slavery tour, a 13-month marathon, was a test of physical and psychological endurance that took a heavy toll on the band, Dickinson and Smith in particular.

(Smith would leave the band during pre-production for 1990’s No Prayer For The Dying. He was replaced by Gillan guitarist Janick Gers.)

For Harris, the greatest challenge came later. In all the years he has led Iron Maiden, only once did he think long and hard about whether he had it in him to keep this band going. It was in 1993, when Dickinson left and Harris was in the process of divorcing his wife Lorraine.

“Pretty awful things were happening all at once,” he says with a sigh. “And I thought the rest of them are going to look to me for strength here, and I don’t know if I’ve got it. There’s that saying: who motivates the motivator? That’s exactly how it was. But it didn’t last long. A few days. I couldn’t carry on feeling sorry for myself. I had to get on with it.”

Dickinson’s replacement was Blaze Bayley, who had previously starred in Wolfsbane, Tamworth’s answer to Van Halen. Harris remains proud of Maiden’s two albums with Bayley: The X Factor (1995) and Virtual XI (1998). “Honestly, I thought some of the songs on those albums were among the best I’ve ever written,” he says. “But those songs were quite dark, probably because of where I was mentally at the time, without even realising it.”

Although Bayley gave it everything he had, he couldn’t match Dickinson’s vocal range or his charisma. And at a time when alternative rock held sway, Iron Maiden’s popularity waned. Harris took an almost perverse satisfaction in adversity. “We were up against it, fighting for our lives,” he says. “Being the underdog again, I enjoyed the challenge.”

But it couldn’t last. In January 1999, Steve Harris made the toughest call of his professional life, telling Bayley that his days in Iron Maiden were over.

“That’s the worst side of being in a band,” he says. “It’s not something I feel comfortable with. Never have done. Never will. But you’ve got to do what’s right for the band.”

With that, the stage was set for the return of Bruce Dickinson, and with him Adrian Smith. Both were ready to rejoin Iron Maiden after years of solo projects, at a lower level than they experienced in the band. But Harris needed convincing.“I was unsure about it for a while,” he says. “I just wanted to make sure they were coming back for the right reasons. So you just take it bit by bit.”

With Dickinson and Smith reinstated in a new six-man line-up now with three guitarists, with Gers having been retained, the band made Brave New World, released in 2000. Harris hesitates to call it a comeback album, but that was the effect it had.

“We made a really strong album, went out on tour, played Rock In Rio and all that kind of stuff ” he says. “I said: ‘This is great.’ And I knew then that we could just carry on as long as we want.”

There had been tension in the past between Harris and Dickinson, dating all the way back to the 80s, but second time around they were older and wiser.

“Bruce and me, we never had fights or anything like that,” Harris says. “There were times when he got on my nerves and I’m sure I got on his nerves. But that’s what it’s like when you’re in a band together for a long time. Certain characters will clash. But there’s a chemistry that works when everybody’s together. It just works. So why would you want to compromise that just for some bullshit stuff that goes down?”

Dave Murray and Adrian Smith are the two most laid-back characters in Iron Maiden. They also have the longest shared history, having become friends as school kids in East London. “We lived two streets away from each other,” Murray says. “We used to jam, and eventually we put a little band together [named Stone Free, after the Jimi Hendrix song], and we’d play in the church hall.”

In that brief period in the late 70s when Murray was temporarily out of Maiden, he teamed up with Smith again in the band Urchin. But after Harris had pulled him back in, his path was set. For the past 47 years he has been at Harris’s side, through all the ups and downs. But he laughs – and Murray laughs often – when he measures the difference in personality and temperament between himself and Harris. “Probably the complete opposite,” he says. “I’m just really chilled out.”

Murray’s Zen-like calm is evident both on stage and off. When he talks about the power dynamic in Iron Maiden, he is deferential, and contentedly so. “The leadership comes from Steve, Bruce and Rod,” he says. “I’m more like a team player, and I’m happy to be in that position. You couldn’t have a whole band with people as laid-back as me, or else nothing would get done.”

On stage he appears to be in his own little world. “There are a million things that can distract you during a show,” he muses. “So you have to be good at tuning it all out.” He has what he calls “a weird analogy”, but it works: “When you play golf, which I love, you’ve got to clear your head. If you can get your brain to shut up for ten seconds, you can hit a good shot. So in concerts I do go into that world of my own. It means I can focus on the music and the pure enjoyment of playing.”

Murray was not immune to the pressure the band were under during that whirlwind period in the 80s, the World Slavery tour in particular. “We needed time off after that, for our sanity,” he says.

But when he considers all of those days, weeks, months and years he has been on the road with Iron Maiden, he speaks with gratitude. “There wasn’t much time to think about it,” he says. “You just lived it. You played music, and you enjoyed seeing a world you’d never seen before. The first time I ever left the UK was with the band. And that was as exciting as the playing – seeing new countries, different cultures. So that, on top of playing the shows, was a total high.”

Only once, in all these years, did he fear that the life he enjoyed with Iron Maiden might be at an end. It was in the late 90s, when Blaze Bayley was fronting the band. “I always liked Blaze,” he says. “Good singer, lovely guy. But we were playing in smaller places, where previously we’d been playing in arenas. It seemed like it was coming towards the end… Until Bruce and Adrian came back.”

Murray’s life is, as he describes it, uncomplicated, and beautifully so. When he’s not with Iron Maiden, he’s with his family at home in the tropical paradise of Hawaii.

“I love playing,” he says. “It’s my favourite thing to do. But there’s a fine balance between touring and having a life at home. In the old days with the band it was constant. You were living it twenty-four/seven. But now, once we finish a tour, I go home, decompress and basically let it all go.”

Adrian Smith is a different kind of laid-back. Not passive-aggressive, but quietly contemplative. He was nicknamed Mr. Indecision by Steve Harris, but as he says: “Steve’s very black-and-white. He just trusts his instincts. I like to absorb and go away and think about it. To me that’s just being sensible.”

The first time Smith was invited to join Iron Maiden, he thought long and hard about it before turning them down. At that time, late ’79, he had high hopes for Urchin, in which he was the main songwriter as well as singer and guitarist. A record deal was a possibility. But Maiden had already signed with EMI and were about to record their first album. Smith recalls how his father had urged him to take the Maiden job. “My dad was a typical working-class guy, experienced in life, and he knew that you don’t get these breaks very often.”

Fortunately for Smith he got a second offer from Maiden just a year later, after Dennis Stratton was fired. This time he jumped at the chance. “Urchin by then was falling apart a bit,” he says. Maiden were flying after a top-ten album and a European tour with Kiss.

Making the Killers album was a daunting experience for Smith: recording at Battery Studios in West London, formerly known as Morgan Studios, where major artists such as Paul McCartney, Pink Floyd, Black Sabbath and many more had created classic albums, and working with a famous producer, Martin Birch.

“I couldn’t sleep for a week before we went in,” Smith recalls. “Martin had worked with Ritchie Blackmore. I mean, Jesus! But he was very good with me, although he could be a bit edgy. He was a karate black belt and sometimes he’d be pulling moves, kicking and shadow-boxing, and then he’d go: ‘Can you do that overdub?’”

It was on The Number Of The Beast that Smith first asserted himself as a songwriter within the Maiden. He co-wrote three songs, including 22 Acacia Avenue, a song he’d performed with Urchin and had written when he was just 16, which goes some way to explaining the lyrical content. “It’s about a young bloke going with a prostitute, an older woman, and losing his virginity,” he says, laughing. “A teenage fantasy at the time!”

On subsequent albums, Smith, an instinctively melodic player and writer, delivered songs that were no-brainer choices for singles, some written alone, some with Dickinson, Harris or both: Flight Of Icarus, 2 Minutes To Midnight, Stranger In A Strange Land, Can I Play With Madness, The Evil That Men Do, Wasted Years, the latter based on a lick that he says “sounded like U2”.

But at the end of a decade in which Iron Maiden had conquered the world, Smith was feeling burned out. “The eighties were very intense,” he says. “For everybody. You’ve got to be mentally strong to get out there and perform every night. And I definitely had some issues. A lot of times I would retreat into myself. But sometimes I just completely freaked out.”

In an era when mental health issues were rarely discussed – especially not by young men in a rock band – Smith felt isolated, unable to express himself other than drowning in booze and coke. “We just kept hammering away,” he says. “It’s what you’ve got to do. And everyone’s got their own problems. They’re trying to keep themselves together.”

It was in 1990 that it all came to a head. “I’d started to feel like I was stifled in the band,” he says. “I didn’t know what I wanted to do.”

The decision was made for him. “They sat me down and said: ‘Are you into it? You’ve got to be a hundred per cent into it. We’re going on tour for another nine months.’ So… that was it. It wasn’t like I said: ‘Right, I’m leaving the band.’ There was a lot of agonising. And like I said before, things are not always black and white.”

For a while he felt okay about leaving the band. “I was kind of relieved, because I wasn’t happy. Everybody knew that. So I bought a house, got married, had kids…”

Near the end of 1991, another major rock band approached him. Def Leppard were searching for a new guitarist following the death of Steve Clark in January of that year.

Smith had known Leppard guitarist Phil Collen since the late 70s. “Phil had auditioned for Urchin back in the day,” he says. “And when I joined Maiden I knew that Phil had also been in the frame. He was mates with Paul Di’Anno.”

As Smith remembers it, there were two key people who recommended him for the Leppard job: photographer Ross Halfin, who had known both bands since the early days of the NWOBHM, and Steve Harris, whose friendship with Leppard singer Joe Elliott began on a rowdy night in 1979 when Maiden played at sticky-floored old joint the Retford Porterhouse. Smith auditioned for Leppard in Los Angeles. “Great guys,” he says. “We played together for a couple of days.”

With his melodic sensibilities, he could have made a good match for Def Leppard. Instead they chose former Dio and Whitesnake guitarist Vivian Campbell. “He’s more of a virtuoso guitarist than I am,” Smith says. “And I guess that personality-wise he fit in.”

However, just a few months after he tried out for Def Leppard, Smith came to the realisation that his heart was still in Iron Maiden. It was a realisation in which emotions he had suppressed finally surfaced.

On August 22, 1992, Maiden were headlining the Monsters Of Rock festival at Donington Park for the second time, and Harris invited Smith to make a guest appearance in the encore.

“It was my missus who said I should do it,” he says. “Just to show there’s no hard feelings. But when I got there I was nervous, and I started drinking whisky. So I was pretty lit up when they went on. I was at the side of the stage, watching them play all the songs I used to play, and I just burst out crying. I was overwhelmed. Up until that point I hadn’t experienced much regret. But it really hit me then. There was a lot of my life in that band, and I was so close to where I used to be.”

He pauses and smiles. “Luckily I had enough time to pull myself together. I hadn’t brought a guitar. I just grabbed one of Dave’s. Janick grabbed me in a headlock and pulled me all the way out onto the catwalk before I’d played a fucking note! And when Running Free started up, I thought: ‘Fucking hell, this is a bit fast!’ But I got through it – just about. And in the end it was a nice thing to do.”

In the years that followed, Smith remained in Iron Maiden’s orbit. His band Psycho Motel opened for Maiden on a UK tour. He then teamed up once again with Bruce Dickinson for two of the singer’s solo albums: Accident Of Birth and The Chemical Wedding. In 1998, a year after The Chemical Wedding was released, Dickinson and Smith were approached about rejoining Maiden. And this time Smith didn’t have be asked twice.

When Steve Harris attempts to describe the various personalities within his band, he laughs and rolls his eyes before carefully measuring his words. “Everyone’s got their little idiosyncrasies,” he says. “I mean, talk about a bunch of characters.”

Of the three guitarists in Iron Maiden, Janick Gers is the most extrovert. Where Dave Murray is happy to go with the flow, and Adrian Smith likes to take his time in collecting his thoughts, Gers is more vocal, highly opinionated, and especially bullish in his attitude to making music.

On stage with Maiden he’s all flash, throwing the kind of shapes that went out of fashion when all those hair-metal bands were killed by grunge in the early 90s. When he’s off stage it’s a different story.

“When I first joined Maiden,” Gers says, “one of the things I heard was: ‘You’re not like a rock star. You’re like one of the punters.’ Yes, that’s exactly what I am. This is part of my life. It isn’t my whole life. You won’t see me walking up Chiswick High Road with my bullet belt on. I can sit in a pub very quietly and have a drink, have a chat about football, religion, politics… anything but music, really.”

Gers first encountered Iron Maiden in the days of the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal, when he played guitar with the band White Spirit, formed in his home town of Hartlepool. In 1981, as a member of Gillan, he befriended Bruce Dickinson, who took every opportunity to get close to his hero Ian Gillan. Many years on, after Gers had temporarily dropped out of the music business and taken a degree in humanities, he and Dickinson reconnected at a charity concert in London. In 1989, while Dickinson was on a short break from Iron Maiden, he recorded his first solo single, Bring Your Daughter… To The Slaughter, with Gers on guitar. The song featured in the film A Nightmare On Elm Street 5: The Dream Child, and was subsequently recorded by Maiden and became their only UK No.1 single.

Dickinson’s collaboration with Gers was developed on the singer’s album Tattooed Millionaire. And it was during rehearsals for Dickinson’s solo tour that Gers received an offer he could not refuse.

As he recalls it: “Bruce had said: ‘Learn some Maiden tracks.’ I said: ‘I thought we weren’t doing Maiden stuff on this tour?’ Bruce said: ‘We’re not. This is for Maiden. Adrian’s leaving the band.’

“Because I was hanging around with Bruce, people might have thought I was trying to get into Maiden, but that was never in my mind.”

Gers’s reasoning is quite simple: “It never occurred to me that anyone would ever leave that band.”

A rehearsal was quickly arranged at Maiden’s HQ. Smith’s gear was still there, but Gers refused to touch it. But as soon as he played a song with the band, any misgivings were forgotten.

“We did The Trooper first,” he recalls. “And I got this adrenaline buzz. My hands were shaking. We did a few more, and they said: ‘You’re in!’”

But it wasn’t all smooth sailing from there. When Dickinson left the band in 1993, Gers was mortified. “I felt like he’d left me by myself.” The years with Blaze Bayley were problematic. “We made it hard for Blaze,” he admits. “We made him sing Run To The Hills, The Evil That Men Do – songs that weren’t in his range.”

When Harris told Gers that Dickinson and Smith were returning to Iron Maiden, his first impulse was to offer his resignation. “My attitude was: ‘I’ll go. If you get Adrian back, it’ll be like it was before.’ But Steve said: ‘That’s not what I’m thinking. If Adrian comes back and you went, it’s like we’d go backwards. But if we have three guitarists it takes it somewhere else.’”

In this triple-guitar formation, Gers is the loose cannon. “Even when I’m in the studio I’m all nervous energy,” he says. “I like to just plug in play. It’s the same when I’m playing live. For me it’s all about intensity. Sometimes you’re at the side of the stage and you’re fucking knackered, you’ve been travelling all day, your knees are killing you. But then you run on stage and – bang! – you’re in another world.

“On stage I feel this aggression, like a volcano going off. I’m completely fucking mental up there. I don’t know why I swing my guitars around. Haven’t a fucking clue. But one thing I do know: if you come near me when I’m swinging that guitar, you’re going to get hit!”

In the restaurant on the 35th floor of a Manhattan hotel, with views across Central Park, Bruce Dickinson flicks through a cocktail menu arranged in somewhat pretentious categories: Earth, Wood, Water. With a boyish grin he holds the menu open at the page headed: ‘Metal’. He orders coffee, but doesn’t really need it. He’s always in the mood to talk.

He begins by discussing a favourite meal that he cooks for himself on tour – egg-white omelette with steamed vegetables. The result of eating it, he delights in saying, is powerful flatulence.

Turning his mind back to Iron Maiden, he remembers the first time he saw the band play live, at London venue the Music Machine in 1980, when Samson, the band Dickinson was then fronting, found Maiden a hard act to follow. It was a chastening experience.

“All these Maiden fans turned up,” he says, “and then immediately Maiden finished they all fucked off, leaving us to play to a hundred punters! I thought: ‘There’s something going on with this band. I think they’re going to be big.”

Samson’s shortcomings were very much apparent to Dickinson during the recording of their album Shock Tactics in January 1981. They had some good stuff in the can, including a ballsy version of Russ Ballards’s Riding With The Angels. But in an adjacent room at Battery Studios, Iron Maiden were making Killers.

“We were all in the bar together every night,” the singer remembers. “And one time when Martin Birch and I were both drunk as lords, he played the whole of Killers to me at full bore, and it melted my fucking ears!”

In the summer of ’81, the stars aligned. “Samson were slowly going down the plughole,” Dickinson says. “And there were lots of rumours about Paul Di’Anno going around.”

After Samson had played at the Reading Festival, Dickinson met with Steve Harris and Maiden manager Rod Smallwood in the backstage enclosure. An audition was arranged behind Paul Di’Anno’s back. But when Dickinson arrived at it, he felt like he’d walked into a wake. “Everybody was just down.”

The gloom lifted when they jammed on some rock classics: “A bit of AC/DC, a bit of Purple; Woman From Tokyo, Black Night.” Then they tried some Maiden songs.

“They’d asked me to learn four,” Dickinson says, “but they’d only got two albums, so I just learned all of them. As soon we’d bashed through a couple, Steve phoned Rod and said: ‘Can we get into a studio tonight?’ And Rod’s going: ‘Fucking calm down! We’ve got some gigs to do with Paul first!’ After that they all went out looking miserable again. I really felt for them – and I felt for Paul, too.”

Once the last dates with Di’Anno were completed, Dickinson returned to Battery Studios, where Martin Birch had set up the backing tracks from the live EP Maiden Japan, minus Di’Anno’s vocals. With the rest of the band watching on, Dickinson recorded vocals for four songs including, somewhat fittingly for a new beginning, Innocent Exile. “When I was done, they all went off into this little huddle for ten minutes,” he says. “Finally they all came out and Steve said: ‘Well, let’s go for a pint – you’re in!’ That night we all went out to see UFO at the Hammy Odeon. We got royally pissed in the bar. And that was it.”

Paul Di’Anno’s failure was the making of Bruce Dickinson. But on October 22, 2024, the day after Di’Anno’s death, it was Dickinson who paid tribute during a Maiden show in St. Paul, Minnesota. In an impromptu speech, he mentioned a song from the band’s debut album. Remember Tomorrow, co-written by Harris and Di’Anno, is arguably the most emotive song Iron Maiden have ever recorded, and Dickinson now believes they should never play it again, out of respect for Di’Anno.

“If ever Paul owned a song, it’s that one,” he says. “I can sing it, and have done. But I think we should leave it with Paul now.”

Di’Anno had succumbed to the pressure of the band’s heavy touring within two years. Dickinson never cracked, but by the mid-80s he was struggling. While he didn’t lose his voice, he feared he was losing his mind. And when he thinks back on that period, he launches into a long, and at times brutal, self-analysis.

“All through the eighties we were working so hard, like eight shows in ten days over the course of eight months,” he says with a shake of the head. “That’s not great if you’ve got a kind of high-performance voice. It can’t perform at that level with that amount of attrition. And then at the end of one year of that, you get to do it all over again. And this goes on for five years… You’re under constant stress every night. You’re suffering from a lack of sleep and self-induced shit, whether it’s chasing after women, whether it’s drugs, whether it’s alcohol. And every day you just get up and do it all again. You’re a bunch of lads together against the world. And nobody’s going to help you if you fall down, so you’re just going to crack on, crack on, crack on…

“You’re not part of normal society. PTSD, dislocation – that’s effectively what you’ve got. And depending on your personality type, you deal with it in different ways. Steve became a recluse. Adrian was drinking himself into an early grave. I was busy shagging everything that moved. And none of it was healthy.

“I remember something that Pete Townshend once said about groupies. ‘The moment you realise that you can click your fingers and manipulate people into having sex with you, that’s the moment you’re going down the slippery slope.’ Up until that moment, it’s innocent. You can’t believe women are throwing themselves at you. You think: ‘Well, this is nice!’ And it is. It’s fucking great!

“But there’s a dark side to this. Where do you stop? When does it become a prop, like alcohol or cocaine? When does this become your reality – when it’s not actually real?

“So that’s when I started doing extracurricular activities like fencing. I was thinking: I’ve got to do something to keep my brain clean. Because I was looking around at our contemporaries in the eighties…”

He carries on: “We toured with Mötley Crüe. Complete fucking casualties, much of it self-induced. And I was like: ‘Please tell me I’m not going to end up like that!’

“I can’t imagine being in a band with somebody who was on heroin, God forbid. When I was in Samson you’d have a joint every now and again. Or you’d do some speed and go: ‘Fuck me! That was horrible!’ And you don’t do it again. But as soon as I went into Maiden, it was just: straighten up, fly right, and don’t blow this. So apart from the odd recreational dalliance here and there in the early days, this has never been a big druggie band. Instead it was our personal lives that went down the shitter.

“And I don’t know whether Steve felt that way, because he doesn’t do touchy-feely, he’s not a great one for expressing feelings – except maybe allegorically in songs. With Steve you have to read between the lines quite deeply.”

Dickinson says that at the end of the World Slavery tour, he reached a crossroads in his life.

“I genuinely thought I should just pack it all in completely,” he says. “Not go solo. Not do anything. Just stop being part of music, because it’s just not worth it. It’s tanked any relationships I might have had, or wanted to keep.

“Adrian’s still got the original wife. I’m on my third, and I don’t want to have any more, thank you very much. I’m very happy with the one I’ve got right now. I’m super-happy, because she’s brilliant for my mental health. I think I’m shocking for hers! But all of us in this band have been through that mill. And you wonder…”

He takes a long pause.

“Sitting here, now… You know what? I think people might find it surprising that I say, on balance, it’s been worth it. Some people might go: ‘How can you even consider it might not be worth it?’ Well I do, actually, right? I do.

“Weighing the scales of your life, there’s a lot of things I missed. My kids growing up. Yes, I saw them, but I didn’t see them to grow up in the way that normal people see their kids grow up. And all the failed relationships, because your mind is skewed. You don’t have a normal set of priorities.”

After the World Slavery tour, when the band began to make the 1986 album Somewhere In Time, Dickinson was, as Steve Harris once said, “off with the fairies”. What Dickinson bought to the table – acoustic folk-rock songs reminiscent of Jethro Tull – were dismissed out of hand by Harris. “There was none of me on that record,” Dickinson says. “I was just AWOL mentally.”

In hindsight, he thinks it “amazing” that he hung in there as the singer with Iron Maiden for another seven years. He describes his time outside of the band, working as a solo artist, as “liberating”. Equally, when he rejoined the band, he felt revitalised and ready for a new challenge.

“When we got back together, Steve, being Steve, was suspicious. Eyeing me up. I just said: ‘Come on, let’s get on with it and do a great album!’ And it was.”

That album, Brave New World, was the band’s best since Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son. It also marked the beginning of a second golden age for Iron Maiden, which has been remarkable not only in the scale of the band’s success but also its longevity. Twenty-five years now. Half the band’s lifetime. But they might not have made it this far after what Dickinson experienced a decade ago.

The band had just finished making the 2015 album The Book Of Souls when Dickinson was diagnosed with throat cancer. It was a long road to recovery, 10 months of treatment. “I had a heavy fucking dose of radiation,” he says. “Thirty-three sessions.”

He says now that he always believed he would pull through. “I felt strong in myself. I was optimistic.”

From the moment of diagnosis, he went through the hypotheticals one by one.

“The first thing on my mind was: ‘I’ve got three children, I want to see them grow up, and so for that I need to be alive. And then, once we get that bit out of the way, let’s see…

“It may sound sort of fatalistic, but my attitude was: if I can’t sing properly, that would be it for me in Maiden. And I was thinking it wasn’t right that Maiden should finish because of that. So I’d help them find a new singer.

“Early on, I made a series of ‘what if?’ decisions. What if I can’t sing again? Okay, then I can’t. What if I could do half of it? Well, then that would be discussion with the other guys: ‘Do you still want to carry on with half a singer?’ I absolutely went through all that.”

After a pause, he smiles. “I got lucky,” he says. “I got through it all, and although my cancer was in that general area, my vocal cords were not affected. So we didn’t have to make that decision, because it all worked out.”

A day after this conversation with Bruce Dickinson, and at the same restaurant table, Nicko McBrain gives his last interview to Classic Rock as the drummer with Iron Maiden.

Superficially, at least, it’s the same old Nicko. The booming voice and unvarnished gor-blimey accent. The warm greeting and easy bonhomie. Except now, at 72, the self-described “grandad of the band” appears to have softened a little with age, and with the Christian faith he has embraced for the past 25 years.

Nothing he says on this day gives any clear indication that he has already made the decision on his future. But what is evident, when he talks about his performance levels behind the kit since he suffered a stroke in 2023, is a trace of wounded pride in a man whose powerhouse drumming has been at the heart of Iron Maiden for more than four decades.

When McBrain joined Iron Maiden in 1982, he was already well acquainted with the band. “I first met them in 1979,” he says, “when I was working with a band called McKitty and we played at the same festival.”

Two years later, on the Killers tour, McBrain was in the opening act, Trust, the politically charged French punk-metal band. “That was when I really bonded with the Maiden boys,” he says. “But the thought of playing for Maiden one day? Back then it never crossed my mind.”

During the Killers tour, he had struck up a friendship with Maiden drummer Clive Burr. “We were very close, me and him. Drummers are like that. I don’t know whether we have that mentality of: ‘I’m better than him.’ At least we didn’t.”

But in late 1982, Burr was out of Maiden, and McBrain was in. On his first album with the band, Piece Of Mind, the opening track Where Eagles Dare began with a thunderous drum fusillade. “That,” he says proudly, “was a great way to introduce myself.” From there he would go on to make another 13 studio albums with the band.

Near the end of this interview there is a brief pause when McBrain’s son strolls into the hotel restaurant to say hello to his dad and give him a hug. A four-day stopover in New York is an opportunity for every member of the band to have time with their families, and McBrain will later allude to this in his farewell notice, stating: “I announce my decision to take a step back from the grind of the extensive touring lifestyle.”

In his parting words to Classic Rock, he uses the present tense when he says: “It’s an honour and a privilege to still be a part of it. The magic of this band’s longevity is we still get on well, and we still have that passion for the music. I think that’s the true essence of Maiden. And after all these years, I still love these guys. I’d take a bullet for them.”

With his emotions rising, he turns to his faith. “I love Jesus and I believe in the Lord, and personally I think: ‘How long is he going to give me?’”

But in the end he can’t resist a joke. “I always thought it would be great to do a Tommy Cooper,” he says, referring to the legendary fez-wearing comedian who died on stage – literally – during a live TV show in 1984.

“What a way to go!” he says, laughing. “But I’m not sure the boys would have wanted that.”

Recently, Steve Harris laughed out loud at something that was written about him. He had been on tour with his other band British Lion, playing in small venues, the audiences numbering in the hundreds, not the tens of thousands that Iron Maiden perform to. On the day of a gig in what is statistically the coldest city in the UK, he read in a local paper: “Steve Harris could be on a beach in the Bahamas in his Speedos, but instead he’s freezing his nuts off in Aberdeen!”

“I thought it was hilarious,” Harris says. “But it did make me think: ‘Yeah, what the fuck am I doing?’”

Harris has lived in the Bahamas for many years, having first visited there in the 80s when Iron Maiden recorded Piece Of Mind at Compass Point Studios in the capital, Nassau. “It’s so beautiful there, I have to pinch myself sometimes,” he says. “But even though I live right on a beach, I can’t laze around in the sun for more than half an hour at a time. I just can’t. I’m not that sort of person. I need to be doing stuff. And playing music is what I love doing most.”

Which is why, at the age of 68, he has two bands instead of one. It’s why he has steered Iron Maiden through 50 years, and why he will continue to do so even without that old warhorse Nicko McBrain behind him.

“Obviously we can’t carry on for ever,” Harris says. “The show that we do is a very physical thing. How long can we keep going? I really don’t know. We were asked that question twenty years ago, and ever since.”

Dave Murray says that Maiden should, eventually, “bow out with dignity and grace”. Nicko McBrain has done so, and Steve Harris reckons he will know when it’s time. Smiling, he says: “You’d like to think your best mate would tell you, wouldn’t you? But I think you’d know in yourself if you can’t cut it any more. And I like to think that we’re still out there giving it large.”

Bruce Dickinson agrees. “Only recently this guy, a big fan, said to me: ‘It’s so great to see Maiden still doing it.’ I said: ‘Yeah, and we’re doing it for real!’ There’s no detuning. This guy said: ‘Lots of bands use backing tracks now…’ I said: ‘No! No, no, no, no, no!’ That’s the day I quit. Or the day we stop. If it’s not real, it’s not Maiden. The idea that you can turn it into the Disneyland Maiden, by using backing tracks, a few tricks…. No! Maiden has to be one hundred per cent real – and fucking fierce!”

The Run For Your Lives tour is a nostalgia trip. “A history lesson,” as Dickinson laughingly calls it. But both he and Steve Harris believe that the drive to create new music has been key to Iron Maiden’s longevity.

“It’s a fantastic back catalogue that we’ve got, but you don’t just rely on that,” Harris says. “We’ve done tours before where we’ve only played the old stuff, but we’ve always continued to make new albums. And even now, I’m still writing all the time. I’ve got so many ideas, it’s ridiculous, insane. I couldn’t finish off all the ideas I’ve had in three lifetimes.”

“God forbid we should make another record!” Dickinson says, laughing. “But we’re booked up through 2025, 2026… so let’s wait and see how we all feel about it.”

What Dickinson feels now is gratitude – and pride in what this band represents.

“I think Maiden is a power for good in the world,” he says. “It really is. You see that every night in the audience. And ironically, we’re now getting to enjoy it as well, whereas in the early days we were so caught up in it that it never occurred to us to go: ‘It’s great.’ Now, I appreciate how fantastic it is. So I’m constantly grateful at sixty-six to be able to still do it.

“And,” he says with a smile, “hopefully do it well.”

Iron Maiden’s Run For Your Lives tour reaches the UK on June 21.