Tonight’s solar eclipse shines a light on our current fascination with the Moon, just a week after the order to NASA from the US Office of Science and Technology Policy to develop a lunar standard time by 2026. Not only does it illuminate a new Space Race for precision-timekeeping on the Moon, it shows just how strange time is at every level.

Even Stanley Kubrick couldn’t account for just how weird time is in space

Even arch perfectionist Stanley Kubrick couldn’t account for just how weird time is in space when, in 1967, he presented American watchmaker Hamilton with the task of designing Heywood’s watch to wear on his Pan-Am shuttle to the Moon station in 2001: A Space Odyssey. The all-round cosmic thinking didn’t go as far as to wonder what good a standard dial and GMT hour window would do for anyone in orbit around the Moon.

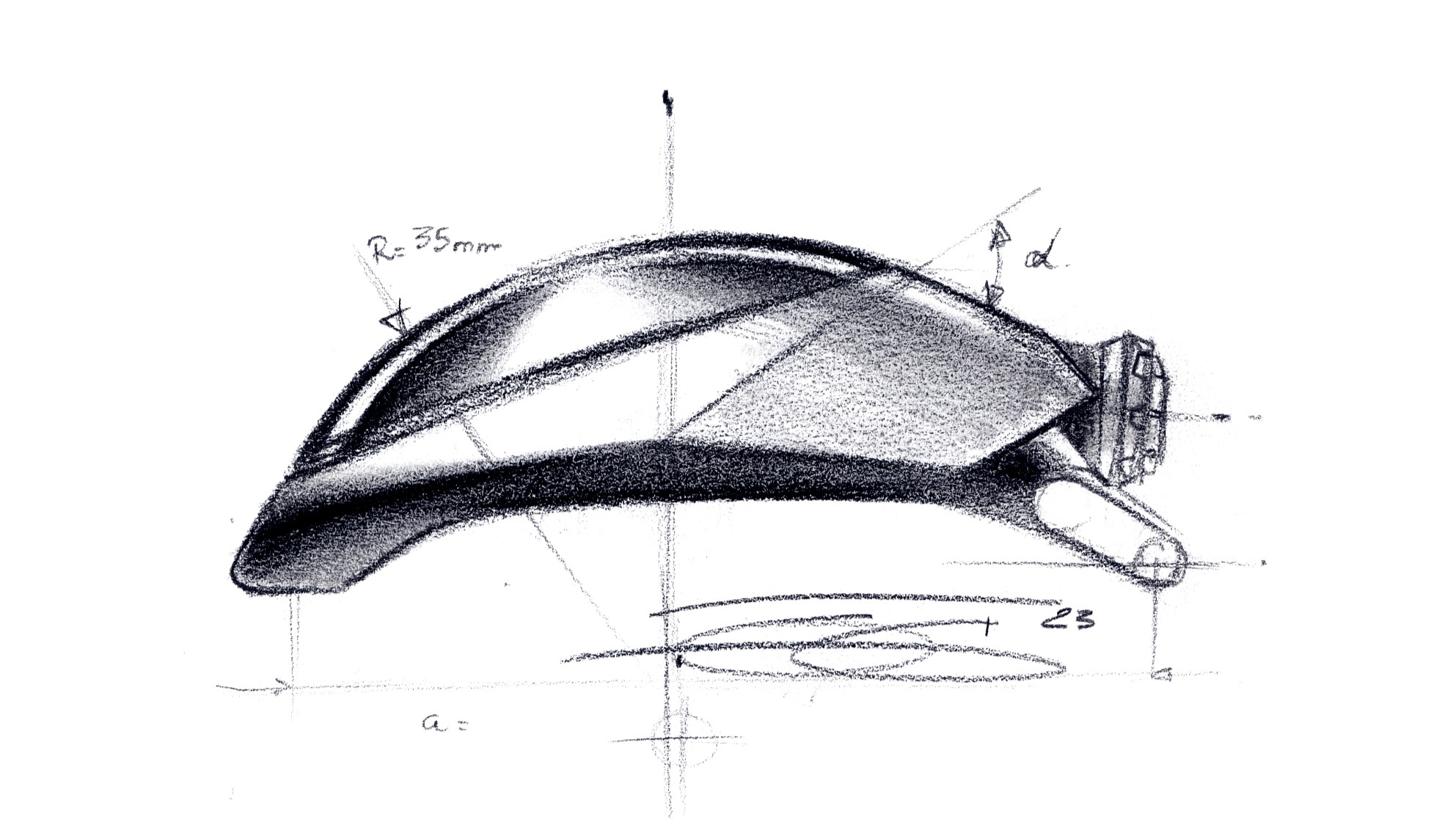

Cut to 2024 and NASA has been tasked to work with international agencies to create a lunar standard time, known as Coordinated Lunar Time (abbreviated to ‘LTC’). Even more intriguing, neo-futurist watchmakers SpaceOne have been working on a solution with the car designer Olivier Gamiette, and their Tellurium watch will launch at Watches and Wonders 2024 in Geneva this week. More of which later because, in order to get to grips with this very modern Space Race, it helps to get a basic insight into the science behind it.

The physics involved in creating unified lunar time are serious and strange

The physics involved in creating LTC are serious and strange, with so many variables to take into account. For instance, at the precision atomic clocks currently run at, it is said you can only know the time of an event that’s passed, with current time an estimate open to revision. Timing on the Moon adds a further layer of complication, including the oddity that time runs faster on the moon (variably 58.7 microseconds per day) thanks to the difference in gravity. Last week, NASA’s Kevin Coggins told the New York Post, not entirely helpfully, that ‘It makes sense that when you go to another body, like the Moon or Mars, that each one gets its own heartbeat.’ A computational nightmare, certainly, but of no major relevance to your choice of wrist wear for a trip to the moon (you have booked already?).

The earth is no use as a time reference, so the sun is the only answer

Lunar time is almost as strange when you zoom out to the macro level. The moon is tidally locked so that the earth is no use as a time reference, leaving the sun as the only answer. This is fine, save that the ‘synodic’ lunar day is 29 days, 12 hours, 44 minutes and 3 seconds (on average – terms and conditions do apply) giving mañana a whole new meaning. So what’s the solution?

You can cheat by using an earth longitude meridian which will be in line every 24 hours (plus 50 minutes because this is the moon). This is the sort of difference you could quite easily accommodate in a wristwatch movement. So, I suggested this to a number of watchmakers in the industry: two replied that it was ‘a very interesting question’ (Swiss for ‘I’ll call you’). Speaking, on condition of anonymity, to a watch-movement designer with deep connections in the industry, it seems that the consensus is that a separate hours and minute train running off the main movement would be the easy way forward (the difference in time speeds being too small to worry about).

This was backed up by Jean-Marc Wiederecht the founder of Swiss movement design specialists, Agenhor, which has worked on complicated technical briefs for Hermès, Fabergé and H.Moser, among other leading watch names. ‘In such a case an interesting function could be to display two different times, LTC and GMT on Earth, but I don’t think you would find the clients for this!’ Wiederecht offers.

My anonymous source came back later and suggested that ‘if you wanted to track the true lunar day on a wristwatch, you’d need something similar to the ‘Equation of Time’ complication that tracks sunset and sunrise times through the year.’ He refused to confirm that anyone was working on such a watch.

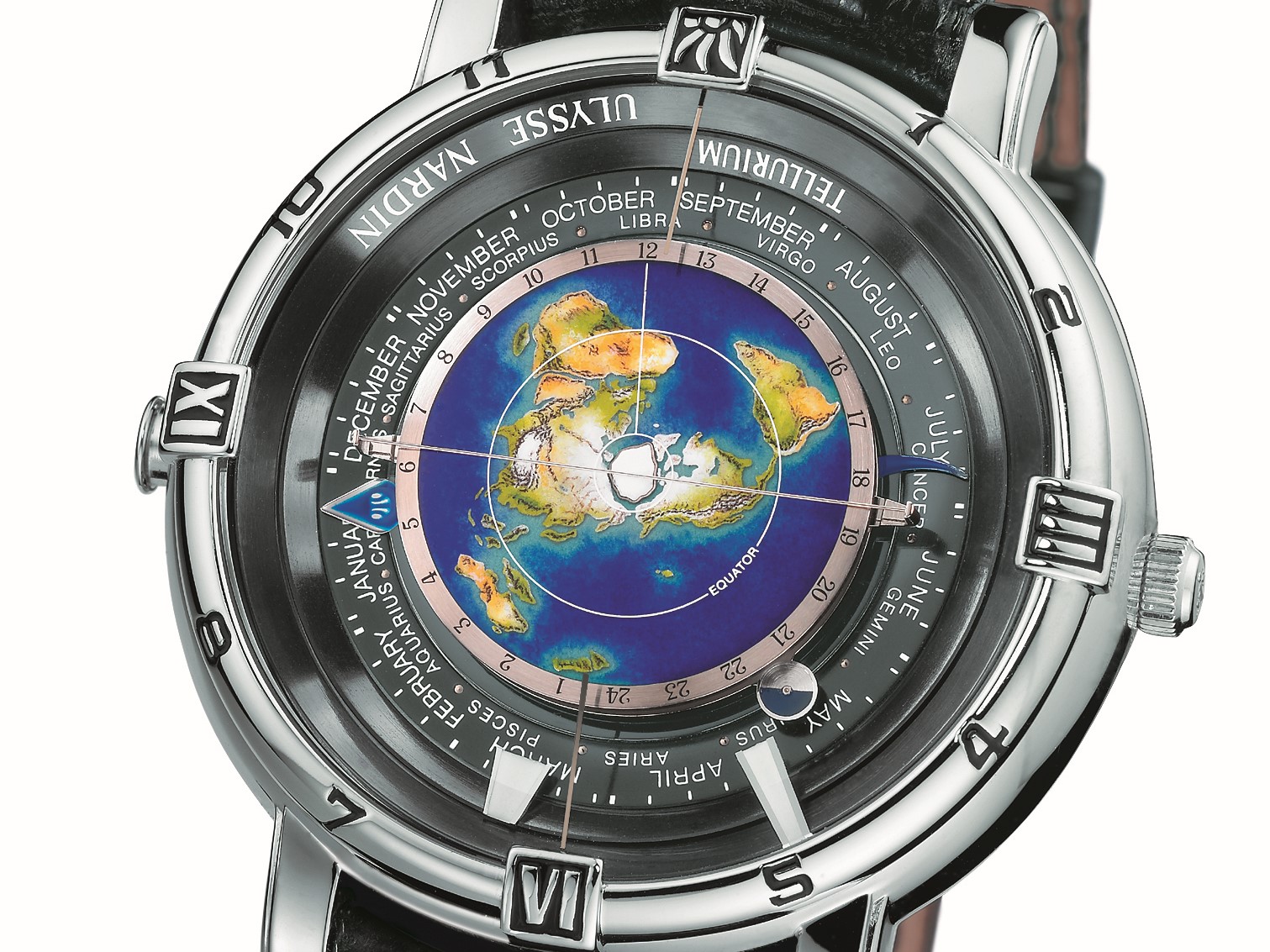

The other approach is to physically model the earth and moon within the wristwatch as in Ulysse Nardin’s fabulous Tellurium watch. One of a trio of astronomical watches designed by watchmaker-inventor Ludwig Oeschlin in the late 80s, the Tellurium shows the relative positions of the Sun, Moon, and Earth with respect to each other. It’s designed to be earth-centric in its display but as they’re made to order, I’m sure Ulysse Nardin could be persuaded to change that – the Tellurium already shows how much of the true moon day has elapsed on the outer ring of the dial.

Bizarrely, while LTC looks complicated, the simplest solution so far launches this week with SpaceOne’s Tellurium, which includes a sun, earth and moon model in a pleasingly spacey design. The brainchild of 38-year-old watch entrepreneur Guillaume Laidet, the design was conceived with French independent watchmaker Thèo Auffret and car designer Olivier Gamiette. Even better, the SpaceOne Tellurium lands at the stellar price of just under €3,000. It launches at Watches & Wonders this week.