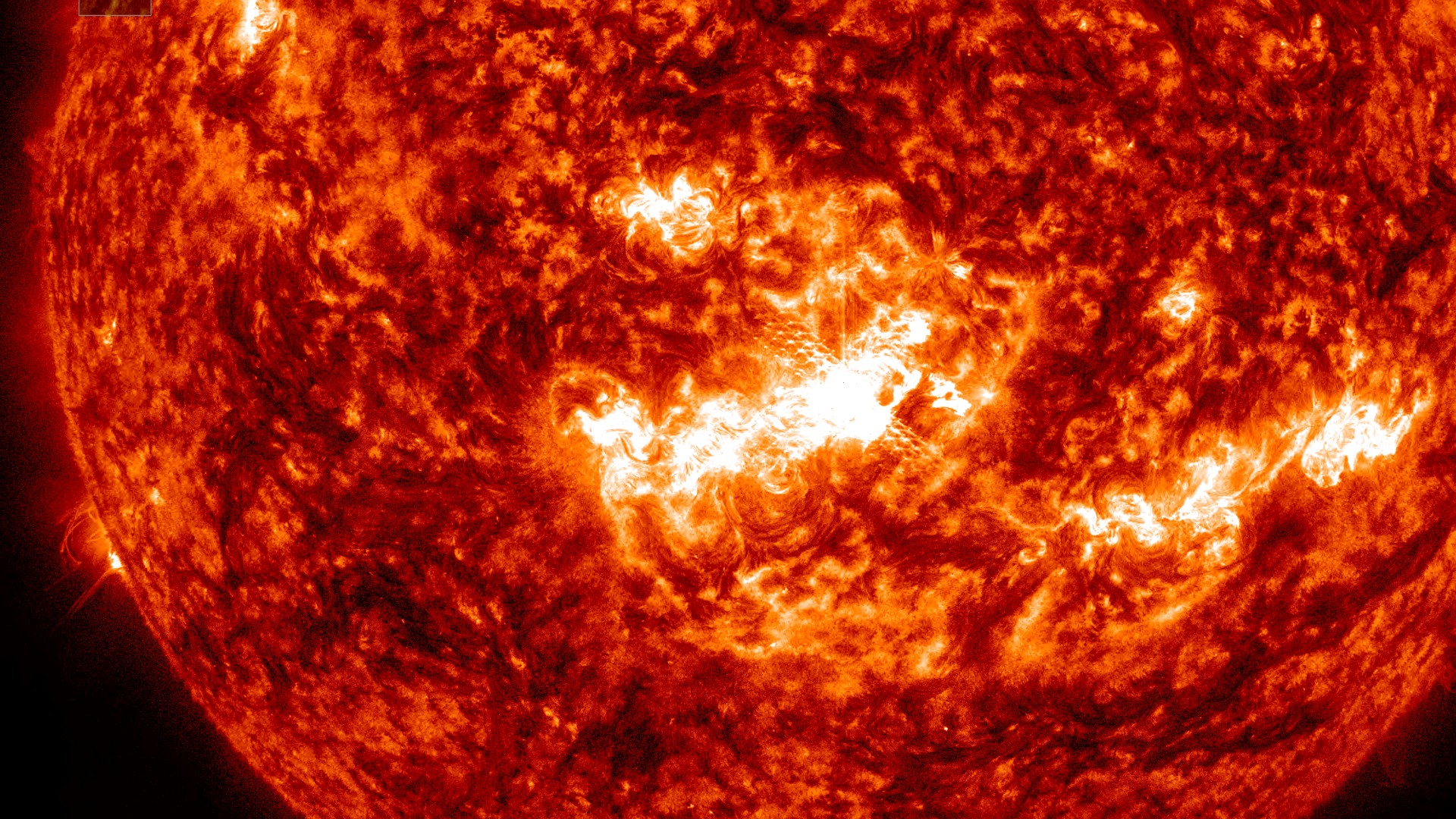

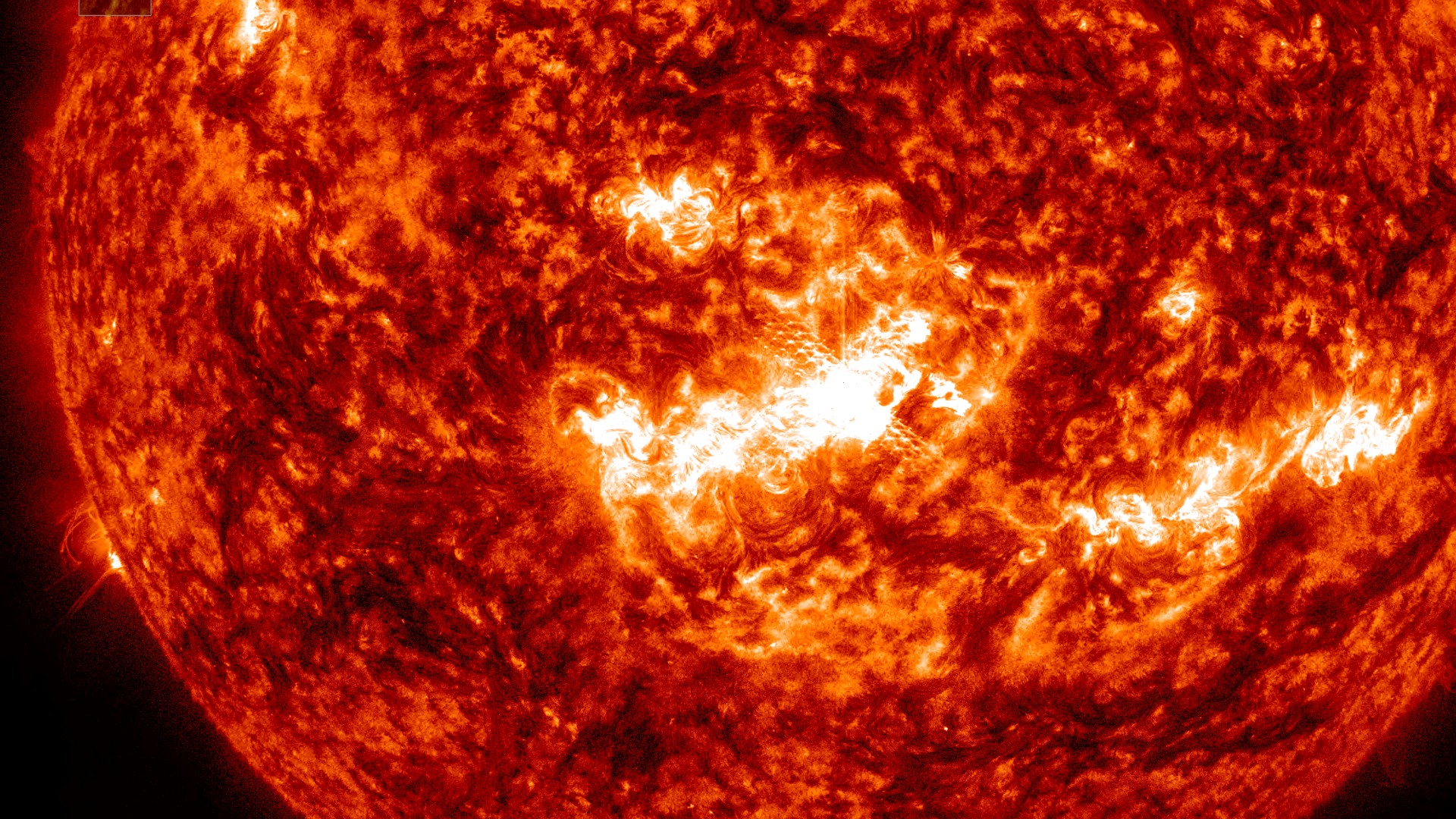

The sun has certainly had a busy weekend.

Not only has our star fired off multiple M-class solar flares, and coronal mass ejections (eruptions of magnetic field and solar plasma), but now it's topped it all off with a colossal X-class solar flare.

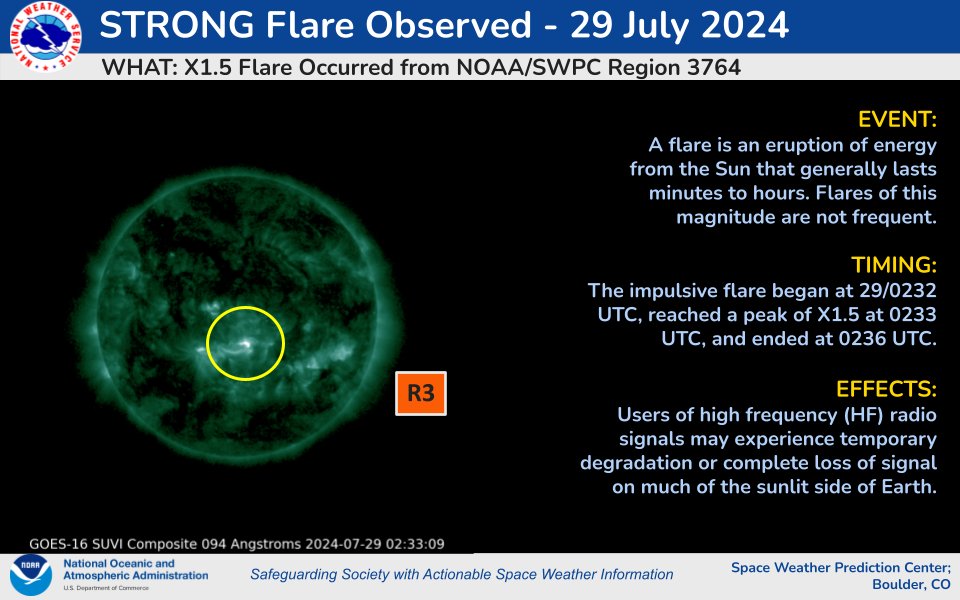

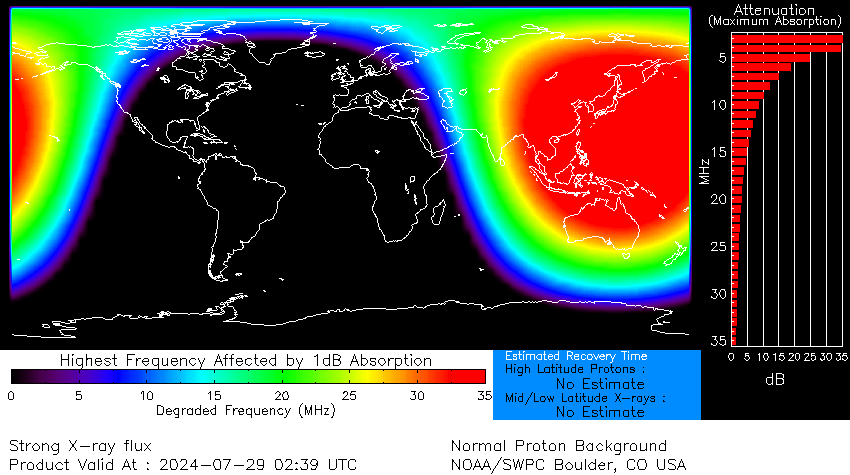

The eruption peaked on July 28 at 10:33 p.m. EDT (0233 GMT on July 29), triggering shortwave radio blackouts across the sunlit portion of Earth at the time of the eruption which included most of Asia and Australia.

Solar flares are eruptions from the sun's surface that release intense bursts of electromagnetic radiation. These flares occur when the magnetic energy accumulated in the solar atmosphere is suddenly released.

Related: May solar superstorm caused largest 'mass migration' of satellites in history

The radiation from solar flares reaches Earth at the speed of light, ionizing the upper atmosphere upon arrival. This ionization creates a denser environment for high-frequency shortwave radio signals that facilitate long-distance communication. However, as these radio waves interact with electrons in the ionized layers, they lose energy due to increased collisions, which can degrade or entirely absorb the radio signals.

This loss of signal was detected over most of Asia and Australia during the recent X-flare eruption.

Solar flares are classified by size into different classes, with X-class flares being the most powerful. M-class flares are 10 times less powerful than X-class, followed by C-class flares, which are 10 times weaker than M-class. B-class flares are 10 times weaker than C-class, and A-class flares are 10 times weaker than B-class and have no noticeable impact on Earth. Each class is further divided by numbers from 1 to 10 (and beyond for X-class flares) to indicate the flare's relative strength.

The impulsive X-flare on July 28/29 measured X1.5 according to Space Weather Live, as it erupted from sunspot region 3764. Forecasters have yet to determine whether an Earth-directed CME accompanied the solar flare according to NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center. Scientists are awaiting coronagraph imagery to determine if an Earth-directed CME follows this activity.

If it did, it wouldn't be the only CME en route. Several CMEs are currently barreling toward Earth and are expected to start arriving on July 30. Their presence could trigger strong geomagnetic storm conditions and auroras at mid-latitudes.