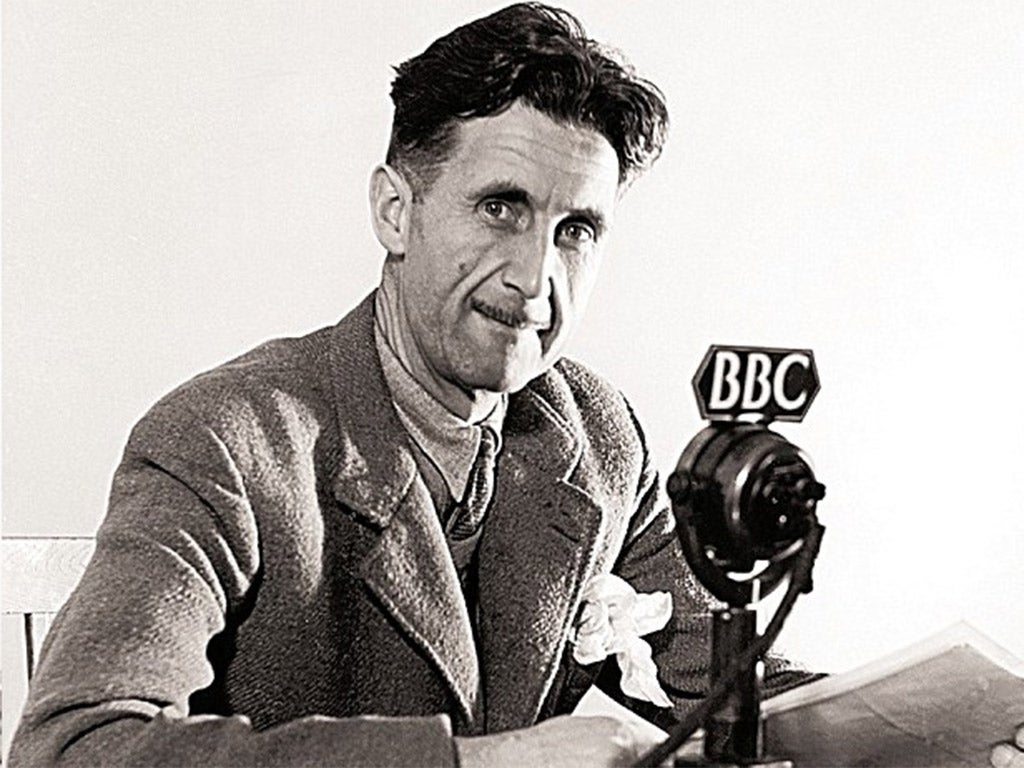

To many, he came close to being a secular saint.

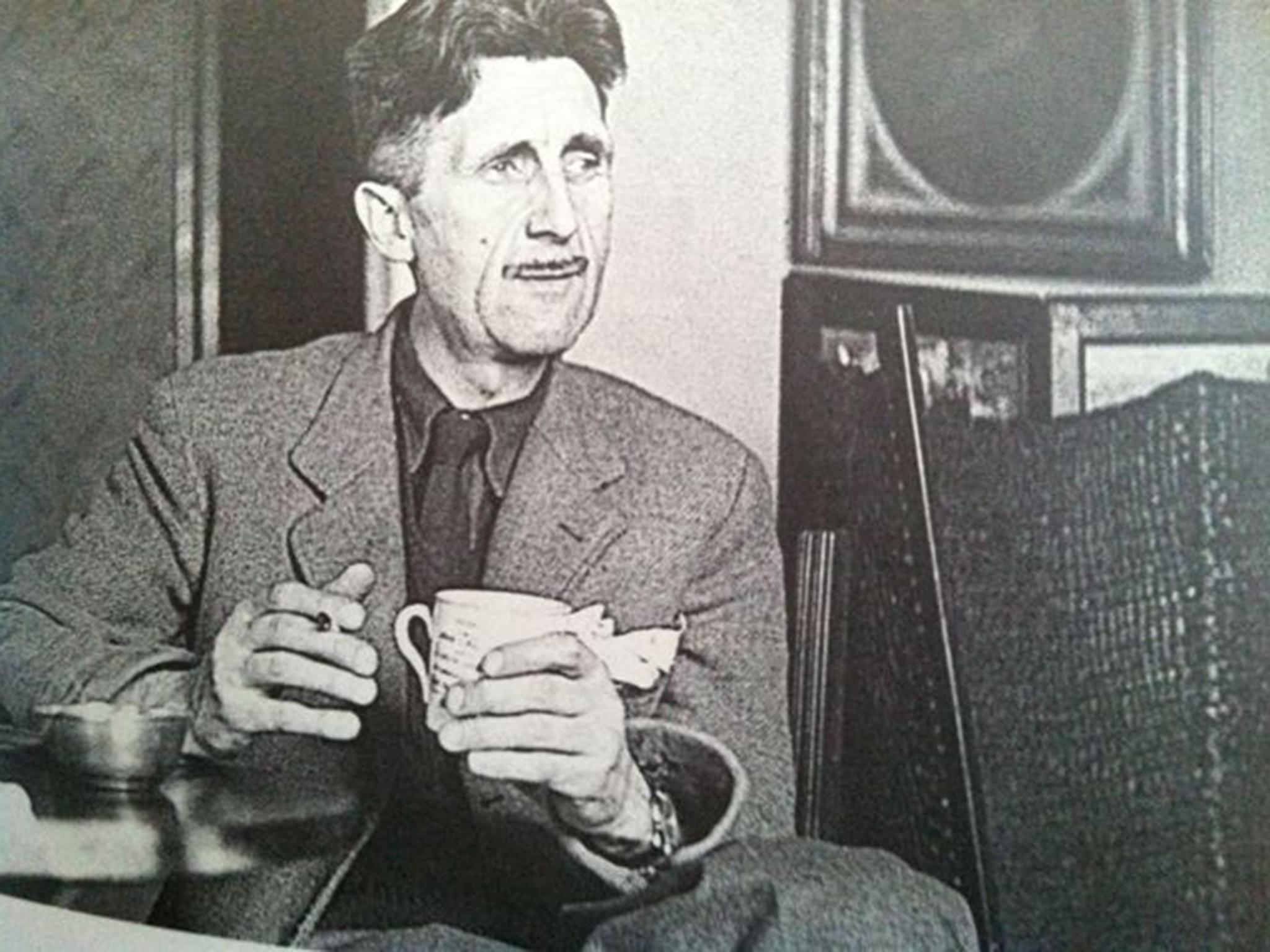

George Orwell, born 115 years ago on Monday, was the writer who challenged the iniquities of imperialism and capitalism, who took a bullet in the throat fighting fascism, and who taught a Western audience about the horrors of Stalinist communism.

That he died young, of tuberculosis at the age of 46, in 1950, served only to enhance his posthumous reputation. He became, in the words of one astute critic, “the James Dean of the Cold War, the John F Kennedy of English letters”.

Death may also have saved him from curdling into the kind of bitter, contrarian conservatism that seems to have been the fate awaiting many a one-time youthful socialist.

Instead, Orwell is often remembered as a man of “genius”, the “greatest political writer of the 20th century”.

The commonly accepted view of the man is encapsulated in the aims of the foundation bearing his name. Through the coveted Orwell Prize, the Orwell Foundation seeks “to celebrate honest writing and reporting, to uncover hidden lives, to confront uncomfortable truths, to promote Orwell’s values of integrity, decency and fidelity to truth”.

And yet there is one blemish – or complication – in the reputation of St George.

It lay hidden until 1996 when Foreign Office file FO 111/189 was made public under the 30-year rule.

The hitherto secret file revealed that in 1949 the great writer had, via his friend Celia Kirwan, given a semi-secret government propaganda unit called the Information Research Department (IRD) what became known as “Orwell’s List”.

Orwell effectively handed over to the British authorities the names of 38 public figures whom he thought should be treated with suspicion as secret communists or “fellow travellers” who sympathised with the aims of Stalin’s Russia.

When the existence of Orwell’s List was revealed in 1996, and when the Foreign Office finally divulged who was on it in 2003, the initial reactions seemed tinged with sadness and hedged about with qualifications.

But the internet was young then.

Now it has grown into a giant bristling with social media channels and anger; swift to judge, slow to reflect.

And so George Orwell, a hero to so many, is now demonised online as a “fake socialist”, a “reactionary snitch”, a traitor, a McCarthyite “weasel”.

“Orwell’s List is a term that should be known by anyone who claims to be a person of the left,” declares one fairly widely circulated condemnation. “At the end of his life, he was an outright counter-revolutionary snitch, spying on leftists on behalf of the imperialist British government.”

“He was an anti-socialist,” asserts another indictment, “corresponding with British secret services and keeping a blacklist of writers.”

So widespread has the vilification become, that “Orwell as snitch” is sometimes played with – not entirely seriously – as an internet meme.

And yet, when you consult DJ Taylor, author of the acclaimed biography Orwell: The Life, you do not encounter boiling indignation.

“I can’t get very worked up about the list,” he says mildly. “I don’t see it particularly as a mistake.

“You just have to see it in the context of the time.”

And that context, reveals Taylor, was explained to him by the left wing former Labour leader Michael Foot.

Taylor recalls: “Foot told me that the great difficulty if you were a left wing Labour MP in the 1940s was working out exactly where your friends stood. You didn’t know whether some were listening to you and agreeing, and then going straight to the British Communist Party’s headquarters in King Street and telling them everything.”

“Another example of the kind of thing they were facing,” says Taylor, “was the man who worked in the Foreign Office in the room next to Orwell’s IRD friend Celia. His name was Guy Burgess.

“There were at least a dozen elected parliamentarians taking their orders from a foreign country,” adds Taylor. “What could be more traitorous than that?”

Years after Orwell listed him as giving the “strong impression of being some kind of Russian agent”, the Mitrokhin Archive of KGB documents revealed that journalist Peter Smollett had indeed been a Russian agent.

Also listed by Orwell, and as a KGB agent by Mitrokhin, was the leading Labour MP Tom Driberg.

Laying aside the irony that Michael Foot was himself once falsely accused of being a KGB agent, it is, then, perhaps no coincidence that the IRD was in fact set up, not by a headbanging Tory, but by Labour foreign secretary Ernest Bevin.

“This was at a time when the Soviet Union was swallowing up what had previously been independent East European states,” says Taylor. “The IRD was producing reasoned expositions, pamphlet literature, telling people on the ground in Eastern Europe why they should resist this kind of stuff.

“But a lot of British people were still seduced by the idea of our ally ‘good old Uncle Joe Stalin’, when in fact the bloke was a mass murdering psychopath. And you were also dealing with some really hardline ideologues.

“So Orwell’s idea was, if you are going to get somebody to write these kinds of pamphlets, they have to be genuine democrats.

“He was a democratic socialist who wanted democratic socialists, not right wingers, to be writing this propaganda. But he wanted them to be people who had seen through the Soviet illusion, not covert stooges for Stalin’s Russia.”

And so Taylor’s anger – such as it is – is reserved, not for Orwell, but for those like the late Labour MP Gerald Kaufman, who greeted the revelation of the list with the “pathetic” remark: “Orwell was a Big Brother too”.

“This wasn’t Orwell denouncing anybody,” says Taylor. “He wasn’t writing public articles in the press saying ‘these people are evil’.

“This was him giving private advice to a friend [Celia Kirwan] who was working for the IRD and wanted to know whom to avoid when asking people to write for her department.”

It should perhaps be noted that Celia Kirwan was a bit more than just a friend. Three years earlier, Orwell had actually proposed marriage to her in the emotional turmoil that followed the death of his first wife Eileen.

Kirwan rebuffed his advances, but some have suggested that Orwell, aware of his failing health, might have been seeking the comfort of a beautiful woman when on 6 April 1949 he wrote offering to name those who “should not be trusted as propagandists”.

He certainly knew the list was not for Kirwan’s eyes only. As noted by Timothy Garton Ash, the historian who persuaded the Foreign Office to reveal the document in 2003, Orwell sent his list to Kirwan with a reference to “your friends” who would read it.

And as Garton Ash also noted, the IRD did not confine itself to relatively innocuous pamphleteering.

In the New York Review of Booksarticle that formed the first detailed analysis of the list’s contents, Garton Ash wrote: “By the late 1950s, IRD had a reputation as ‘the dirty tricks department’ of the Foreign Office, indulging in character assassination, false telegrams, putting itching powder on lavatory seats and other such Cold War pranks”.

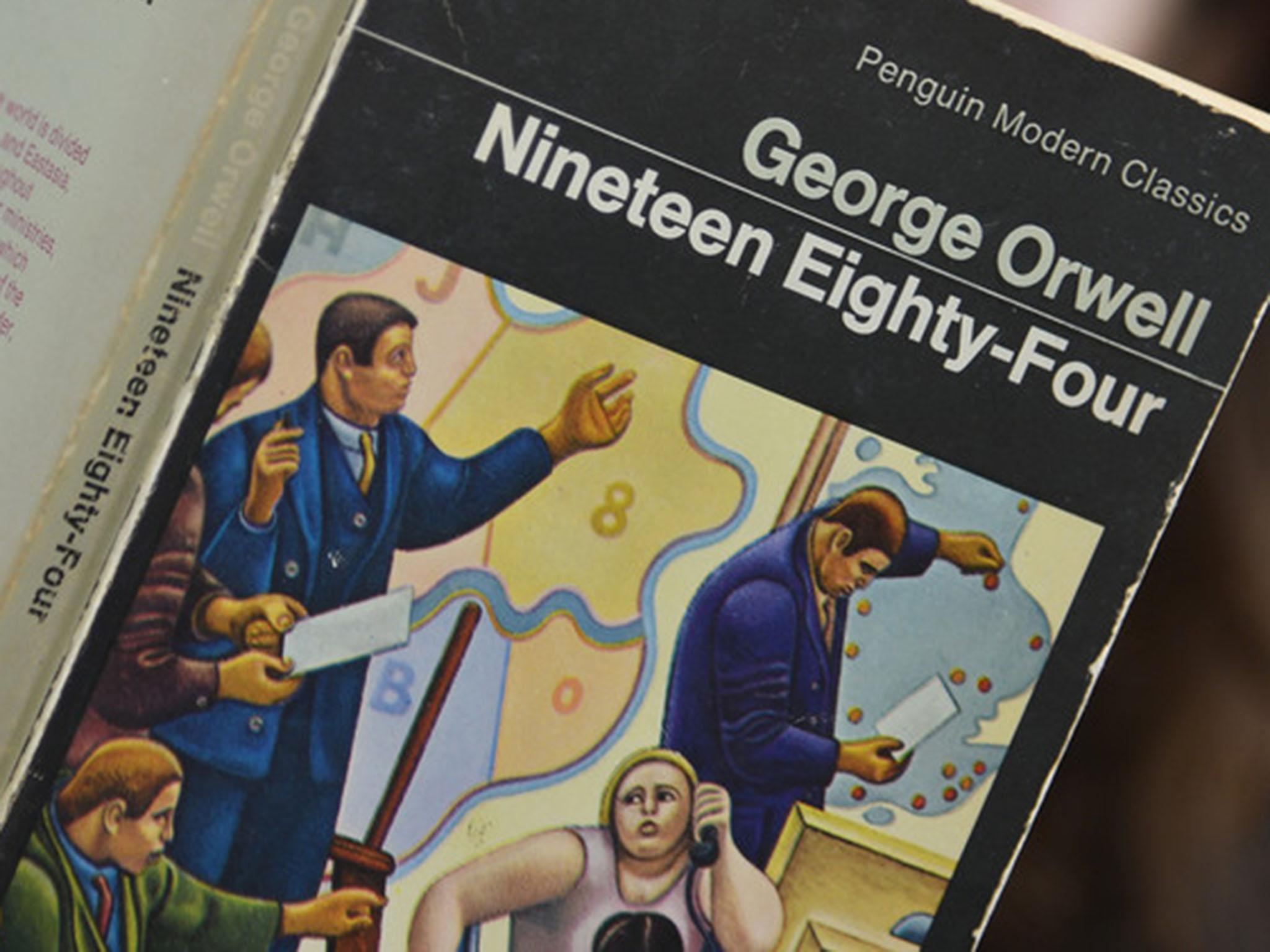

When he sent his list to Celia Kirwan in 1949, Orwell might not have known that this was the IRD’s direction of travel, but of all people, the author of 1984, who envisaged the Ministry of Truth, should surely have been aware of the possibility.

That said, as Garton Ash also wrote, not much seemed to have happened to the people on Orwell’s List (apart from missing out on the IRD pamphlet-writing gig). It seems their names weren’t even passed to MI5 or MI6.

In America, Hollywood actors blacklisted during the McCarthy era had their careers and lives ruined. In England, Michael Redgrave appeared on Orwell’s List in 1949 and starred in the film adaptation of Orwell’s novel 1984 seven years later.

Peter Smollett, named by Orwell as a likely Russian agent, got an OBE.

In other words, what happened to those on Orwell’s List seems to have borne no comparison to the fate of Big Brother’s fictional victims or the real millions who died in the purges and repression ordered by Stalin.

“The list invites us to reflect again on the asymmetry of our attitudes toward Nazism and communism,” wrote Garton Ash, whose own experiences of being spied on by the communist East German Stasi informed his book The File.

What if Orwell had given the government a list of closet Nazis, he wondered. “Would anyone be objecting?”

And in truth, there does seem a certain asymmetry in the online articles of denunciation.

Indeed it is hard not to sense the inspiration of Private Eye’s (fictional) veteran class warrior Dave Spart in some of the articles condemning Orwell as “a social democratic traitor collaborating with the capitalist state against revolutionaries trying to create socialism.”

“Sure, the USSR did a lot of objectionable things,” says one writer. “But … Western imperialist countries commit much more heinous crimes throughout the world every day.”

Which is one way to gloss over the Gulag.

A stronger charge against Orwell might be that of antisemitism. The private notebooks that formed the basis of the list he sent to the IRD included labels like “Polish Jew”, “English Jew”, and “Jewess”.

But Orwell did also devote an entire 1945 essay to discussing how best to combat antisemitism, while having the honesty to admit – and regret – his own occasional lapses into jokes at the expense of Jews.

And at the moment, antisemitism might be a problematic charge for some left wingers to level.

Taylor, though, is convinced that some amongst “the newly emergent hard left” would secretly love to unleash something against Orwell.

And yes, by “newly emergent hard left”, he does mean some Corbynistas.

Younger party members, Taylor concedes, might not have the personal memories of the Cold War, still less an instinctive understanding of the context in which Orwell produced his list in 1949.

But, he adds: “I am a Labour Party member. I have been to hear Corbyn speak and noticed how an awful lot of the people there were aged left wingers for whom there had not really been a place in the Labour Party for the last 20 or 30 years.

“An awful lot of the hard left these days would pay lip service to Orwell as a beacon of sanity, while secretly having doubts.

“There are still a load of extreme lefties out there to whom Orwell is this snivelling little Trotskyite telling them things they don’t want to hear and pointing out things that shouldn’t be pointed out because they get in the way of the revolution.”

And to the ideological, Taylor would add the psychological: “Tall poppy syndrome – Orwell is this secular saint, so let’s have a go at him.”

This battle over Orwell’s reputation, of course, is more than just a matter of idle literary historical curiosity.

Its relevance to the political struggles of today is suggested by the remark of one of the more ferocious online critics.

“George Orwell,” he says, “was the first in a long line of Trots-turned-neocons”.

It is certainly true that far-right commentators have started trying to co-opt Orwell to their cause, even to the point of suggesting that the man who once chased a fascist across a battlefield with a fixed bayonet would deplore the Antifa movement.

This, says Taylor, is pretty much what Orwell feared.

“At the time he was giving Celia Kirwan his list, 1984 was about to be published. Orwell’s great fear was that right wingers would use it as a piece of anti-communist propaganda, and that’s what happened. Immediately after 1984 was published, it was used by the CIA as a propaganda tool.

“Orwell wrote a very interesting letter to people in the US saying: ‘Look, this is not so much anti-communist as anti-totalitarian.’

“He feared what right wingers would do with 1984, but thought it was the price you had to pay for exposing evils like totalitarianism.

“And a writer can’t be blamed for how their books are used by people who are determined to twist meaning for malignant ends.”

Taylor, though, can’t help wondering whether Orwell would really have been that upset by the comments of “slightly disconnected people” on the far left of the internet.

Orwell himself, he points out, never sought secular saint status. Quite the reverse: “He was very wary of that kind of thing. In an essay on Gandhi he effectively says that when people start being referred to as saints there is something very odd about them and it usually ends in disaster.”

Instead Taylor has a sneaking suspicion that Orwell might have been rather amused by his online detractors.

“People undervalue Orwell’s wry sense of humour,” he says. “David Astor, who used to edit the Observer and employed him, told me about the time Orwell came to him saying, ‘You should hear the abuse I have been getting from some of the communist newspapers.’

“Orwell said: ‘They call me a fascist octopus. They call me a fascist hyena.

“Then he paused: ‘They’re very fond of animals’.”