In January 1925, doctors in Nome, Alaska saw the stirrings of a diphtheria outbreak, a deadly infectious disease. The closest city with the antidote (a simple antibiotic) was Anchorage, 500 miles away. It was the dead of an Alaskan winter, with temperatures dipping to negative 50 degrees Fahrenheit. There was only one hope left for transportation: a sled dog relay.

Twenty mushers volunteered to traverse the Iditarod Trail in the Great Race of Mercy with their trusty Siberian huskies. One novice, three-year-old sled dog led the final stretch; his name was Balto. He and his musher, Gunnar Kasson, thundered into Nome just before dawn on February 2 with the life-saving serum.

(While Balto has gotten all the credit — including a statue in Manhattan’s Central Park and a Disney animated movie — it was actually an older, more experienced sled dog named Togo who covered the most ground.)

Now we know a little more about the hero dog. Researchers throughout the U.S. and Sweden sequenced and analyzed Balto’s genome, publishing the findings in a study on April 27 in the journal Science. Part of the Zoonomia Project, this study details Balto’s heritage and brings genomics a big step forward.

Sequencing Balto

The study confirms a few traits we already know about Balto as well as some others that one can’t discern by appearance alone. Researchers used the information they gleaned from his genome to predict his eye color, coat color, and standing height.

“Balto represents this kind of snapshot in human and dog history because the two are obviously completely intertwined,” first author Katie Moon, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Santa Cruz’s paleogenomics lab, tells Inverse.

The DNA sample the researchers analyzed came from the skin of the taxidermied Balto’s underbelly. “We gave him a tummy rub,” Moon jokes.

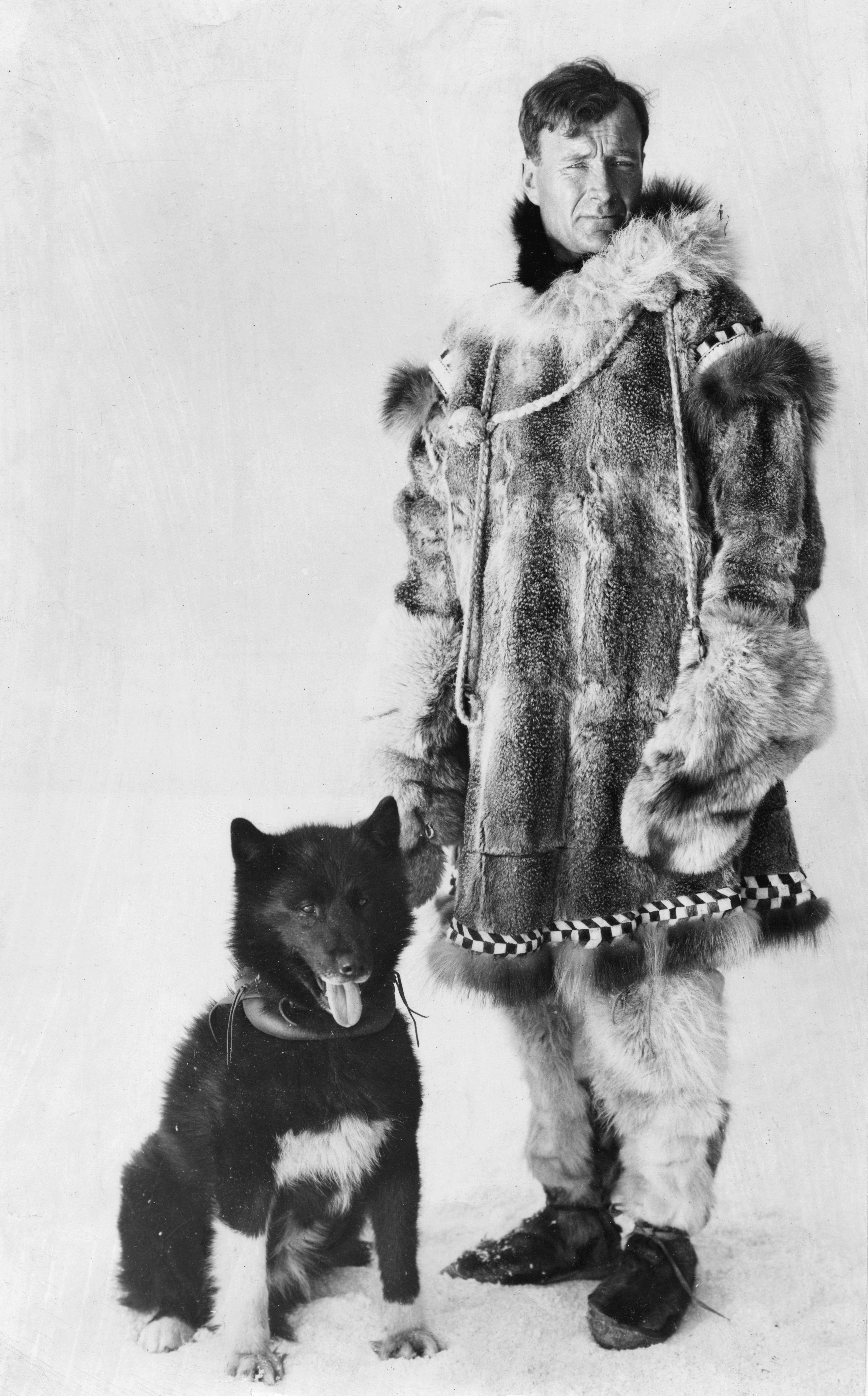

Balto’s taxidermied body is preserved at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, but it’s become “sun-bleached,” warping the details of his coloring. Black-and-white historical photos also obscure some of his physiognomy.

“We were able to build on what we knew about him,” Moon says. “Even though he was so famous, we can still find out new things.”

The genes behind the hero

Balto wasn’t like the floofy, handsome Siberian husky of today. (Though he was both floofy and handsome, photographs confirm.) Bred by a musher named Leonhard Seppala, this heroic dog was built for Alaska’s harsh conditions and grueling physical labor. His genes also allowed for a particular diet.

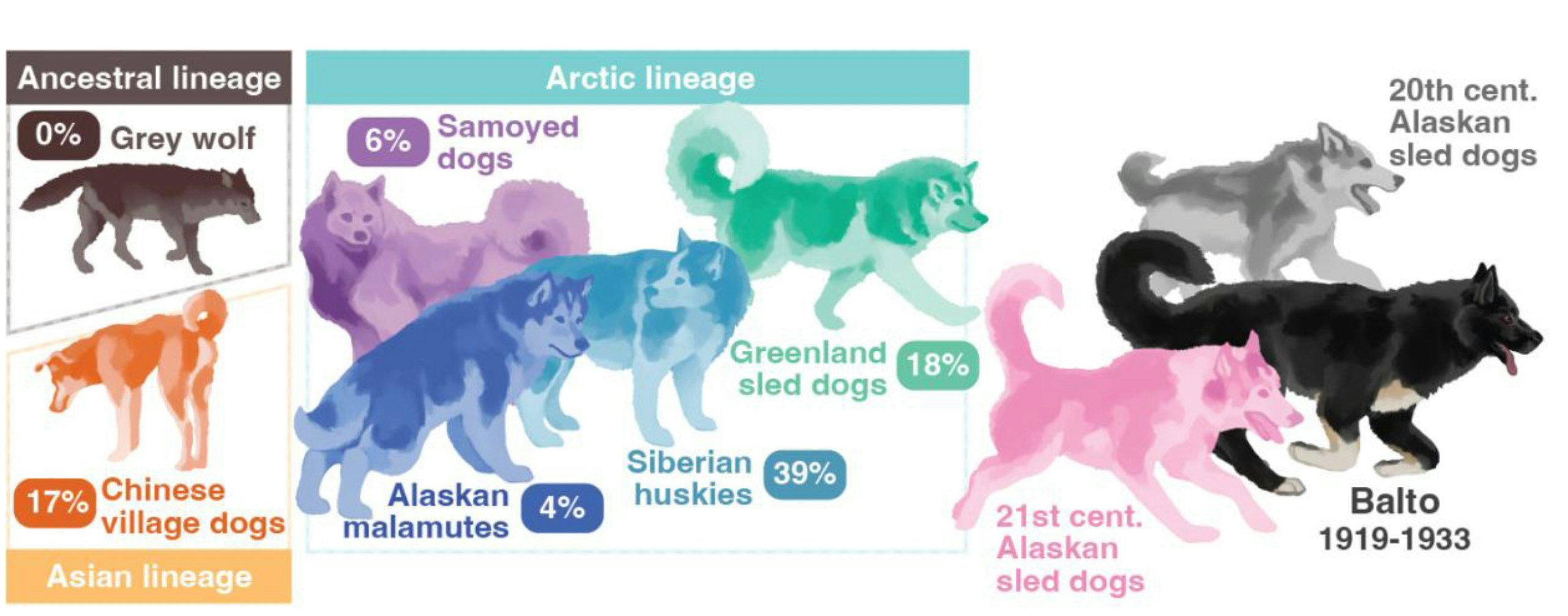

According to the researchers’ findings, Balto was adapted to starch-rich diets, as evidenced by a particular gene. The ancestral MGAM gene, which Greenland sled dogs and wolves have, boosts the animal’s ability to digest starch and therefore use it as energy. This hero dog was a “cool intermediate” of wolves and domesticated dogs because he could eat lots of starch in addition to meat, but isn’t as well adapted to a starchy diet as modern dogs.

Balto also had “unusual function variation.” Moon and her team found genes related to tissue development that would impact skin thickness, coordination, joint formation, and other physical traits that would prepare these sled dogs for harsh Arctic conditions. These genes aren’t unique to Balto but were characteristic of other dogs in his kennel. In other words, his genetics predisposed him to weather the bitter cold.

A perfect storm

Part of this study’s importance, Moon says, is how it utilizes genomics to understand adaptation and selective breeding. Her team wanted to probe what sequencing a single genome could say about a group; moreover, what is revealed when that single genome is compared against dozens of others? This study compared Balto’s genome against that of 282 other dogs in search of overlaps that may indicate adaptation to different environments.

Moon says that between advanced technology and comparative high-quality datasets, there was a “perfect storm” for this research.

Genomics of a good boy

Moon relinquishes this data to the public, hoping that others continue to build on it.

“I hope people use it for a million and one applications,” she says. Every genome sequenced immediately becomes publicly available, allowing anyone to pick up where the researchers left off. “I think one of the coolest things about genetics is that every time we step forward, we step forward as a group.”

Moon plans to apply genomics in animal conservation efforts. Another paper in the Zoonomia Project focused on using genome sequences to predict which animals could become endangered.

Dogs with jobs continue to help and even save hundreds of thousands of lives every day as service animals, rescue hounds, bomb sniffers, and more. These dogs are all selected for an array of traits, especially strong for their breed, and trained to hone those skills. But, as all dog owners know, each pet fulfills its duty every day by simply being the best.