Big building supply companies have fended off competition by wrapping desirable blocks of land in legal constraints on generations of New Zealanders, alarming the Commerce Commission into issuing a far-reaching warning. Jonathan Milne reports.

Nestled down a private lane in Auckland's Mount Wellington, the new Parkside Residences 138-apartment complex is described to potential buyers as "an attractive city-fringe development that breathes new life into this mature suburb".

To the south, it looks over neighbouring Sir Woolf Fisher Park; to the north it looks out towards the rolling curves of volcanic cone Maungarei, and beyond that Rangitoto.

To the east (and this isn't in the marketing materials) the apartment balconies overlook a vast Bunnings hardware warehouse, its truck-loading bay and nearly 300 car parks.

READ MORE: * The mystery of the Hawke's Bay housing covenants * Big hardware retailer faces court action for blocking competition * Auckland's 'unforeseeable' sprawl ends protective covenants on rural land

There's something else that's not in the marketing materials – indeed, Ray White estate agent Steve King says he didn't even know about it until he was called by Newsroom.

According to a Bunnings spreadsheet supplied to a Commerce Commission inquiry into anti-competitive behaviour in building supplies, lawyers for the Australian-owned DIY chain have placed a covenant over the land on which Parkside Residences has just been built.

The new owners may not build a hardware store on the site, or even advertise hardware ... for 999 years.

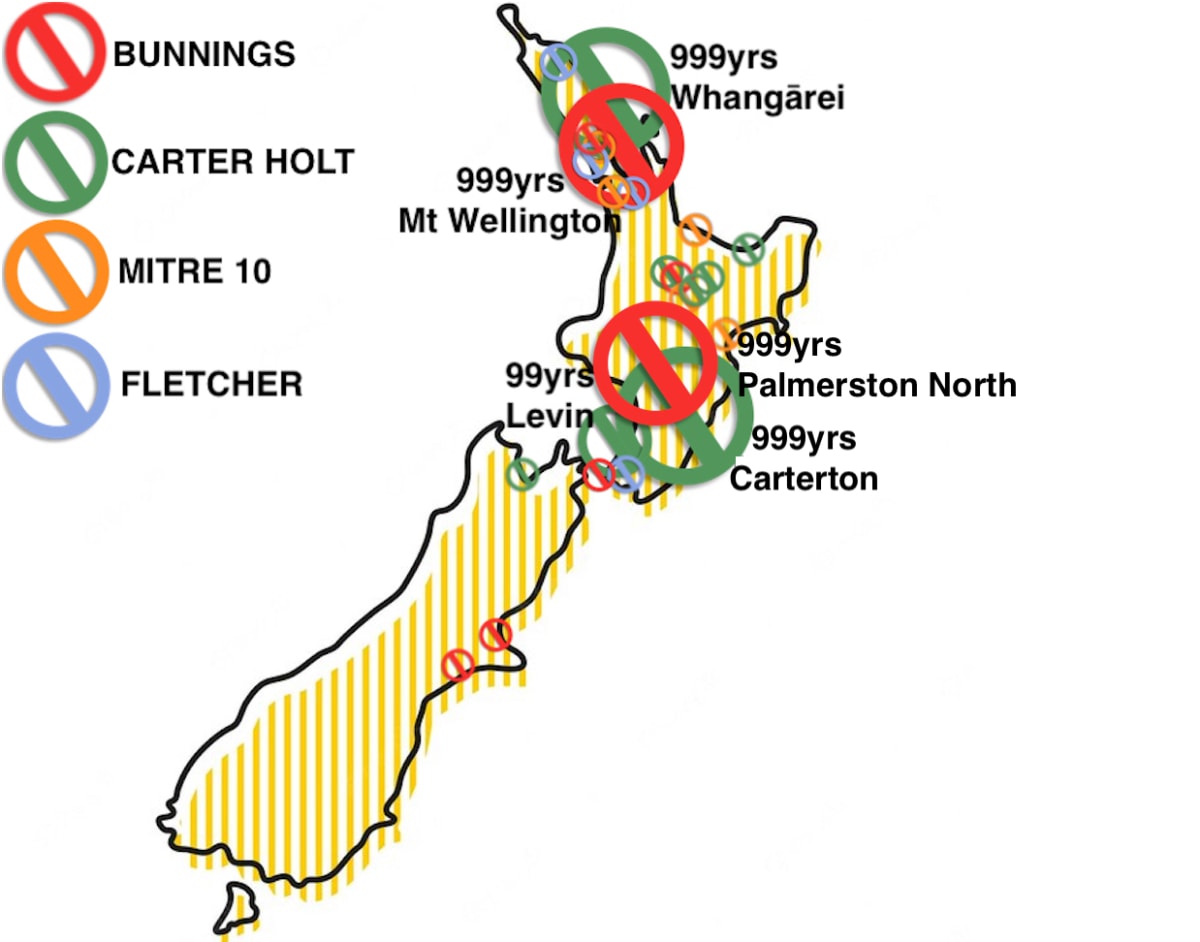

Documents released to Newsroom under the Official Information Act list about 60 land covenants covering more than 100 blocks of land, and another 80 exclusive lease deals put in place by Bunnings, Mitre 10 Mega, Tumu Merchants, Placemakers and its parent company Fletcher Building, and Carters and its parent company Carter Holt.

Among them are 999-year covenants set in place by Bunnings in Mount Wellington and Palmerston North, and by Carter Holt in Whangārei and Carterton. Carter Holt has also placed a 99-year encumbrance on properties in Levin.

Coming soon after the discovery of similar widespread use of anti-competitive covenants by petrol stations and supermarket owners, the scale of the problem has alarmed the Commerce Commission. It heard examples of smaller merchants like ITM being stopped from leasing land due to covenants lodged by the big players.

"The party benefitting from the land covenant may enjoy reduced competition, enabling it to maintain or increase its market share, increase prices, reduce quality, service and innovation, and potentially worsen terms to the detriment of consumers." – Antonia Horrocks, Commerce Commission

"Store covenants with long durations are especially concerning," the commission says in its report, published in December. "Because covenants are attached to (or run with) the land, store covenants would bind any third parties who subsequently acquire or lease the site if they were still active. This may result in other merchants being precluded from operating on a site, even after the merchant who benefits from the covenant has left the area."

Now, the commission is proposing a wider inquiry into the use and abuse of "anti-competitive" land covenants, which it says may be limiting competition across many sectors of the New Zealand economy.

The commission’s competition general manager Antonia Horrocks says these covenants can limit the freedom of landowners to choose what or how they buy or sell, or who they do business with. "The party benefitting from the land covenant may enjoy reduced competition, enabling it to maintain or increase its market share, increase prices, reduce quality, service and innovation, and potentially worsen terms to the detriment of consumers," she says.

The Government introduced legislation under urgency on Budget night last year, to ban the use of covenants by supermarket chains Foodstuffs and Woolworths, amid concerns they were restricting competition and driving up food prices.

There are legal limitations on the use of covenants in other sectors, but they're not at all comprehensive and the Commerce Commission has found them difficult to enforce. It's currently prosecuting NGB, the operator of Mitre 10 Mega in Tauranga, which the commission alleges bought land to prevent a Bunnings Warehouse being built on it.

"Registering land covenants of that nature for whatever term (most of the covenants were for significantly shorter periods) is no longer business practice." – Denver Simpson, Carter Holt

Ahead of a wider inquiry and potential law change, one of the big building supply companies has acted pre-emptively to remove its covenants.

Carter Holt Harvey general counsel Denver Simpson says the company terminated its 999-year covenants earlier this year, by removing them from the relevant land titles. It also terminated all of the other land covenants it notified to the commission last year.

"Registering land covenants of that nature for whatever term (most of the covenants were for significantly shorter periods) is no longer business practice and hasn’t been undertaken for more than 10 years," Simpson tells Newsroom.

In the Mt Wellington case, Bunnings no longer owns the land – King says it sold the land block to developers fronted by Sydney-based Austino Group, who battled through Covid lockdowns to build the seven-storey block, and are now marketing the first tranche of apartments. They are advertised from $599,000 for a one bedroom apartment, up to $787,000 for three bedrooms.

King is marketing the apartments. He denies previously knowing of a 999-year covenant on the Barrack Rd land title. "Until titles are issued, we have no idea about what has or hasn't been put on," he tells Newsroom. "It's probably because the land initially was owned by Bunnings and then sold to the developer. So I'm guessing that that's got something to do with it.

"Until I see the title, I wouldn't know it's there. And until you've just brought it up, I wouldn't have thought anyone would have any concern about it."

"I wouldn't have thought anyone owning an apartment there is going to be wanting to start up a hardware business out of their apartment, which they couldn't do legally anyway." – Steve King, Ray White

"When you're selling these off plan, the developer has mechanisms for dealing with this sort of thing as part of the process of when a title gets issued."

He points out that it is unlikely to materially constrain most buyers in the short-term – they would be buying for somewhere to live or rent out, not somewhere to sell hardware or hang advertising hoardings.

But that's now – what about in 10 years, or 50 years – or 999 years? The apartment block won't be there for ever.

Newsroom asks if, now he has been told of the covenants, he would be ethically and legally obliged to disclose them to any potential buyer. "Now that you've raised the issue, I'll probably need to look and see what the covenant is all about, but I wouldn't have thought it's a big deal," King says.

"I wouldn't have thought anyone owning an apartment there is going to be wanting to start up a hardware business out of their apartment, which they couldn't do legally anyway."

Bunnings' headquarters in Australia has been approached for comment.