A young woman receiving end-of-life care says she is “just waiting to die” as an agonising three-year wait for a kidney transplant has left her “living like a prisoner”.

Diana Isajeva is one of approximately 7,000 patients who are on the waiting list, according to the NHS Blood and Transplant service (NHSBT) – the highest figure in a decade.

The 29-year-old was due to have a transplant last year but was denied it at the last minute, after the living donor she was matched with pulled out just 24 hours before her planned surgery.

Data from NHSBT shows that the rate of families giving consent for their loved ones’ organs to be donated has dropped – despite a change in the law in 2020 aimed at boosting the number of organs available, which means that consent for donation is now presumed after death.

Professor Peter Friend, transplant lead for the Royal College of Surgeons (RCS), said decreasing donor rates are a “big challenge” and that it is concerning that the number of donations has not yet recovered to its pre-pandemic level.

“There are more patients than there are donor organs available, and it manifests itself, obviously, as a waiting list going up after having come down for a number of years. So yes, [it’s] a big challenge,” he said.

NHSBT, which is responsible for organ donation, said it was not clear whether the fall in the consent rate had affected the size of the waiting list, but warned that “hundreds of people are still dying unnecessarily every year waiting for transplants”.

Data for 2021-22 shows that just over 400 people died while waiting for an organ transplant, while more than 600 were taken off the list because they had become too ill for surgery.

Of the thousands of people on the waiting list, the highest number by far are awaiting a kidney transplant. These patients make up more than 70 per cent of those in need of a transplant.

Ms Isajeva, from Cardiff, has been waiting for a kidney transplant for three years. She has the autoimmune disease lupus, which was previously managed with chemotherapy, but she is now experiencing kidney failure and is receiving end-of-life care while she urgently awaits a donor.

She made a public appeal after donor lists were suspended during the pandemic, and although a donor was found, they backed out 24 hours before the operation.

Ms Isajeva told The Independent: “Waiting for a live or deceased donor kidney transplant is like being in prison, but you haven’t committed any crime. I can’t go further than two hours away from my house if I wish to remain active on the transplant list.

“I am not allowed to travel due to extremely poor health. Most days I am so poorly I can’t leave my bed even to eat. Waiting for the transplant is never knowing whether you will live long enough to receive a kidney.

“Even if you do, will it be a success? Will I ever feel OK? Also, organ failure is an invisible disability, unless someone sees my chest port. I get judged by everyone a lot, and people don’t understand how I can be so sick and still look OK.

She continued: “Every single day that I am still alive, I see as a blessing and a chance to still do something good for the world. I know what it feels like to be all alone with your problems, and I don’t want anyone to feel like I felt so many times.

“For a young person, it is a very long time to put all your dreams and aspirations on hold, and it feels so unfair. Some days I feel extremely hopeless and depressed that the transplant will never happen and I will just die waiting.”

Ms Isajeva said the public need to be aware that the opt-out law doesn’t mean you will necessarily become a donor after death, and that it is important for people to share their wishes with their loved ones.

Consent rates dropping

The change in the law means that all adults are considered to have agreed to organ donation unless they have already opted out. However, in cases where someone has not made an indication either way, families still have the final say.

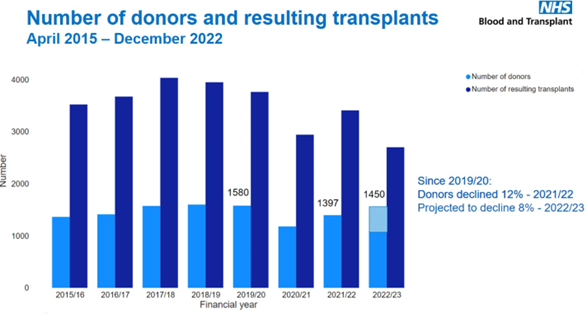

New figures published by NHSBT show that donation rates are expected to be 8 per cent lower in 2022-23 than in 2019-20, before the law was introduced. However, there is set to be an increase since 2021-22, from 1397 to 1450 by the end of the period.

The proportion of families giving consent for donation after death has fallen in England from 69 per cent (around 2,500 donations) in 2020-21, when the new law was introduced, to 61 per cent (1,500) in 2022-23.

For Wales, the rate of consent rose from 59 per cent (100 donations) when the law was introduced in 2015, to 77 per cent (150 donations) in 2018-19. However, these rates have since fallen back to 2015-16 levels.

Anthony Clarkson, director of organ and tissue donation at NHSBT, said it was difficult to decipher the impact of the law change because it came into force in England during the pandemic, and because the whole of the NHS is still in a recovery phase.

He said it was unclear why the consent rate had dropped, but that there had been an increase in families declining “due to a known wish of their loved one not to donate”.

When a family is not made aware of a person’s wishes before they die, the consent rate falls to just 58 per cent, according to NHSBT.

A spokesperson said it was “difficult to know” whether the consent rate had affected the size of the waiting list.

“What is important, though, is that hundreds of people are still dying unnecessarily every year waiting for transplants,” they added. “We know that if everyone who says they support donation talked about it and agreed to donate, more lives would be saved.

“We need families to support their loved one’s decision, and agree to donation when approached if they know that’s what they wanted.”

The jump in the waiting list comes after a year of increased pressure on emergency departments, and strikes by NHS workers, which have led to surgeries being cancelled.

Speaking to The Independent, Professor Friend of the RCS said the rising number of patients awaiting organs and the decrease in donors following the pandemic were “concerning”.

“We’re very aware of the support of the public, over the years; very aware of the reasons for disruption in recent years, particularly following Covid; and very aware of the need to get back to where we were before, where there was increasing and effective public support, with donation rates increasing.

“I’m concerned that recovery is slower than we might have anticipated, but I believe the public supports this very strongly, and I believe that we will regain the trajectory,” he said.