There’s one day that stands out to me in the many months of covering Gaza as a Middle East specialist at the BBC. I stood in front of my team, pitching – for the second time – the story of a five-year-old girl trapped in a car with her murdered relatives: Hind Rajab.

I had been following the Red Crescent’s constant updates as they tried to save her. The BBC department I worked for chose not to cover her story that day. It was only after the Israeli military killed her, shooting the car 300 times with her inside, that our public broadcaster chose to say her name. And when it did, the article headline didn’t even make clear who had done what. It shied away from coming to a conclusion.

The BBC failed Hind. And it has failed Palestinian children again in pulling the documentary Gaza: How to Survive a Warzone, following external pressure over a 13-year-old narrator being related to a deputy agriculture minister in the strip, which is administered by Hamas. It had the option of keeping the version with a line of context on this, ultimately standing by the truth at the heart of the film: that Israel is harming Palestinian children.

This decision prompted me and more than 1,000 others – including Gary Lineker and Miriam Margolyes – to sign an open letter condemning the move.

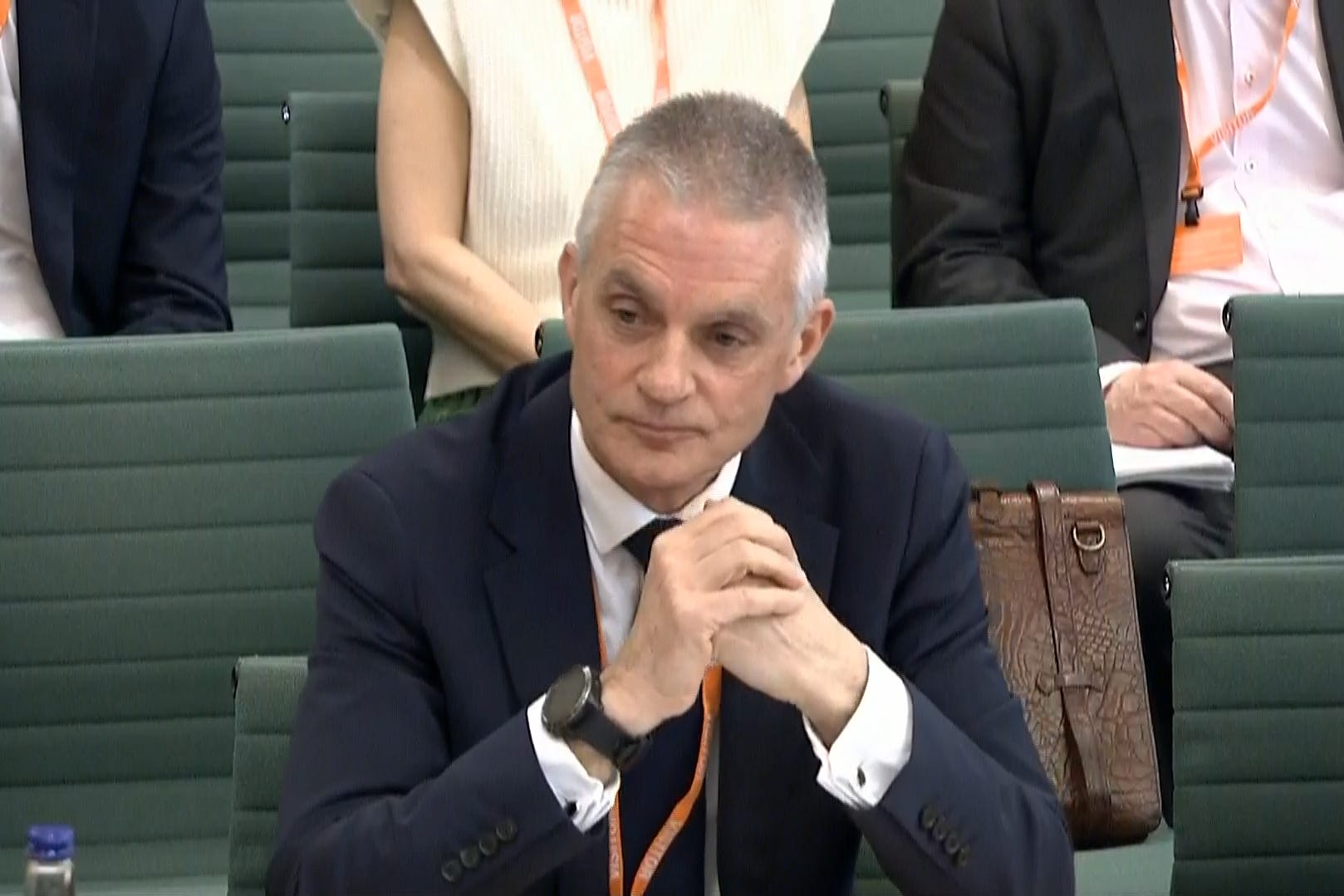

Yesterday, director general Tim Davie and chair Dr Samir Shah faced the Culture, Media and Sport Committee over the organisation’s work, where MP Dr Rupa Huq asked if they had thrown “the baby out with the bathwater” in removing the documentary. While the BBC says there were “serious flaws” in how the film was made, it has failed to acknowledge an overall lack of editorial integrity in covering Gaza. During the session, Tim Davie agreed on the need for an independent review into the BBC’s overall Middle East coverage – a move that’s sorely needed.

I was at the BBC for five years, starting out as a researcher and eventually becoming a newsreader and journalist. In that time, I covered Covid-19 outbreaks, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Hindu nationalism in India. But it was in covering Gaza that I saw a shocking level of editorial inconsistency.

Journalists were actively choosing not to follow evidence – out of fear. For months, I watched the BBC repeat one of its gravest editorial errors around climate change: debating a phenomenon long after the evidence showed it’s real. We deserve a public service broadcaster that follows the evidence in a timely manner, without fear or favour. Editorial bravery is key.

I’m about to make a bold claim: truth exists.

For the journalist, at least, it exists in the form of reasonable, evidence-based conclusions. In a world where claims are constantly competing, a journalist’s job is back-breaking: it is to investigate and come to conclusions, rather than setting up constant debates – no matter who this angers and no matter how much work it takes.

Impartiality has failed if its key method is to constantly balance “both sides” of a story as equally true. A news outlet that refuses to come to conclusions becomes a vehicle in informational warfare, where bad faith actors flood social media with unfounded claims, creating a post-truth “fog”. Only robust evidence-based conclusions can cut through this.

Every day, the worst photos and videos I will ever see appeared on my X (Twitter) and Instagram feeds. I would slowly look through them, listing the stories from Gaza I’d pitch at the morning meeting. These images were a branding iron to the brain. Searing.

The first time I saw a man crushed to death by an Israeli bulldozer, the image was so blurred I might have been looking at a tuft of poppies. As it sharpened, I saw the pulp of a man’s flesh pressed into the ground, orange and red. For months, I would think of him and my chest would convulse. But I refused to turn away. Absorbing the weight and extent of this evidence was my job.

To see such overwhelming evidence every day and then hear 50/50 debates on Israel’s conduct – this is what created the biggest rift between my commitment to truth and the role I had to play as a BBC journalist. We have passed the point at which Israel’s war crimes and crimes against humanity are debatable. There’s more than enough evidence – from Palestinians on the ground, aid organisations; legal bodies – to come to coverage-shaping conclusions around what Israel has done.

In 2018, the BBC issued long overdue editorial guidance to its staff, stating: “Climate change IS happening.” There was a sigh of relief from climate scientists, after years spent warning the organisation its debates were harmful. Coverage would now be rooted in this evidence-based conclusion.

When will the BBC conclude that Israel IS violating international law, and shape its coverage around that truth? As the old saying goes, the journalist’s job isn’t to report that it may or may not be raining. It’s to look outside and tell the public if it is. And let me tell you: there’s a storm.

Karishma Patel is a former BBC newsreader and journalist