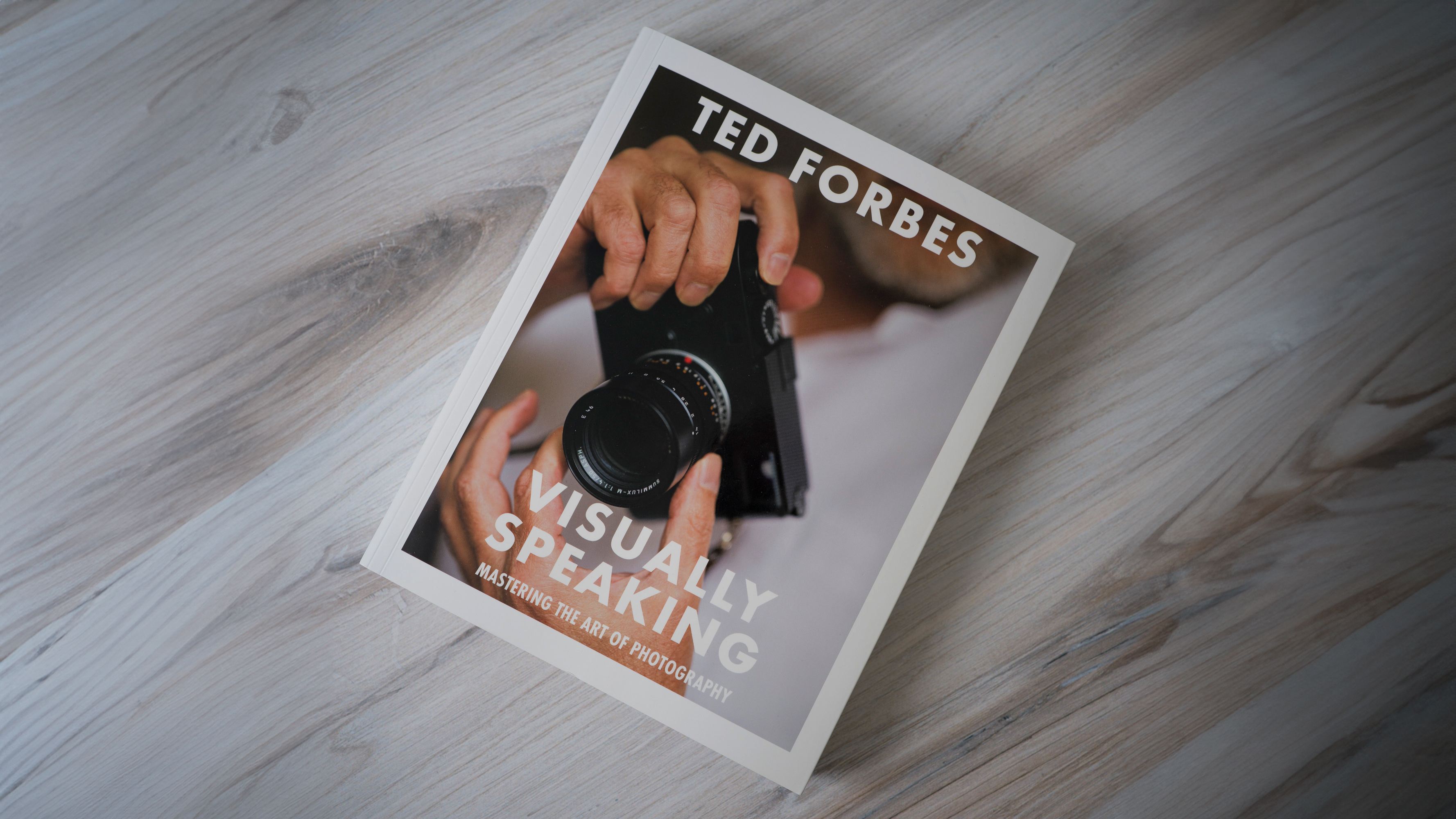

Ted Forbes has been a guiding voice in photography education for years, inspiring countless photographers, myself included, through his YouTube channel The Art of Photography. His debut book, Visually Speaking, is out today and provides the reader with an insightful and comprehensive guide to mastering photography as a visual language.

In this exclusive interview, Ted discusses the making of Visually Speaking, his thoughts on photography as an art form, and his hopes for the next generation of photographers. For a more in-depth look at the book – along with my thoughts – I have written a separate article that delves into its pages.

Whether you're a seasoned professional, or just starting, Ted's wisdom is invaluable and reflects his passion for helping others grow their craft.

I always like to start with the question: What first drew you to photography as a medium and capturing the world through a lens?

My dad is an illustrator and he used to be a commercial illustrator so all of my parents' friends were in the creative arts somehow. One of his best friends was a photographer named Greg Booth, a very successful commercial photographer locally, who had studied with Arnold Newman. He was an assistant with Newman for a little while before Newman told him he needed to be shooting and not assisting. He was a good friend of my father's and I remember going over to their house for dinner, I was probably eight or so at the time, and their house had art from all around the world. I didn't know who Arnold Newman was at that age but they had black and white photographs all over the house and I remember they had the portrait of Stravinsky at the piano. I remember staring at that and I just found it just fascinating.

I think I was probably drawn to it because it's such a heavy graphic image with the piano lid, and I was always fascinated by the fact you can tell it's a piano even though you don't see the whole piano – all you see is the lid and the portrait in the bottom. That stuck in my mind.

I looked up to Greg quite a bit and I thought he was cool and loved what he did so I guess I was in probably sixth or fifth grade and for my birthday, my parents got me a little Kodak 110, the rectangular camera that took the cartridges – I thought it was so cool.

I remember going over to my friend's house and I brought my little camera with my film and every week I'd save up money and mom would take me over to the one-hour developing. So I always shot just because it was fun.

Could you speak a little about how your photography journey continued?

As I got into high school, I actually got into music. I played guitar and, long story short, I went to an arts high school and then onto college as I wanted to be a film composer. I worked for a company during the tech boom that did music software for educational stuff and it was obvious that the music industry was drastically changing. The only way that I was going to have a career doing that would be to move to Los Angeles and ghostwrite for somebody for another 10 years. I had no patience back then and the idea of moving to Los Angeles didn't appeal to me.

I started trying to figure out other things I could do. Photography was always something I'd kept up with and right around then, digital cameras had come out and the first commercially available decent camera was a Canon Rebel or something like that. I saved my money up and I bought one, thinking I wanted to get serious about this, but it drove me back to film photography again and got me really serious about that.

So one thing led to another and around 2008 podcasting was becoming a big thing and you could do video podcasts, YouTube wasn't quite up and running at that point. For the first year, I released my show as a podcast and it helped me to talk about photography because I thought that there was a hole for an educational resource as books were heavily rooted all around the same thing.

It later turned out that the YouTube side and the education side were wide open, so I went down that path and I'm still here years later.

I'm thankful that you did as your YouTube channel – The Art of Photography – has been a fountain of inspiration in my career. When did you start your YouTube channel?

October of 2008 so we're 16 years in now – it's wild!

It's interesting when I started doing it honestly, I needed to learn how to do some video stuff for work because video had just become affordable. It used to be that a video camera was 10 grand, but they had just released those tiny Panasonic cameras that look like toilet paper rolls, and along with what Apple was doing with iMovie, all of a sudden you had a very affordable way to edit video.

I was working at an art museum at the time, they wanted to get into video production and didn't know what to do. So, I remember somebody came into my office one day and said, "Hey, I know you shoot photos. Would you like to do video?" And I said, "Oh, yeah." And they said, "You know how to do it, right?" And I said, "Yeah, yeah, yeah, definitely."

It was a total scramble. I realized really quickly I would need a little project on the side where I could make my mistakes and have fun with it, then when I came to work, I knew what I was doing.

I was going to do a video-based photography podcast and I would do maybe 10 of these and I'd talk about various things. I mean they're really cringe if you go back and look at those early videos, but it was just a short-run thing. I wanted to know the whole process of actually posting them online. It was an RSS feed back then, and the next thing you knew somebody would send me an email. All of a sudden I realized there are people who have a similar interest from around the world and it became a conversation, and that excited me so I kept doing it. A friend of mine then said, "You might want to post your stuff on YouTube."

I remember putting a whole bunch of videos up one day and then I kept doing it and eventually I stopped posting the podcast because it just didn't have the same draw. YouTube had really taken off so I did it just as a hobby for about seven years before I decided 10 years ago in 2014 to monetize it. I realized I was so busy at work and so busy doing the show I had to pick one or the other. I decided to take the leap of faith and just go for it, and I'm glad I did – I've made it 10 years!

I am certainly glad you did too. Those early deep dives into photographers's work really ignited that photography spark for me.

I'm glad to hear that! I mean, for me those were fun to do, it was basically studying out loud. I would go research that stuff because I wanted to know it and then I would get excited about it and I just wanted to share it with somebody else.

That leads us nicely to your new book Visually Speaking: Mastering the Art of Photography. It is unlike any ‘how-to’ photography book I have ever read. I wonder if you could speak on the inspiration behind creating the book, and how it differs from others?

The history of photography how-to books has been pretty mediocre, to be honest. They cover a wide range of things, but it's either more at the business end like – 'how to get into shooting weddings' or 'making a living with photography', or on the other end you get books that are all technical with each covering the same thing.

I remember years ago when I was starting to get serious about photography, going up to the used bookstore one night and I found all these old photography books from the 60s and they were all the same thing. They would go through everything but they would only talk about shutter speeds, the exposure triangle, and at that time, the film development process, and print development process.

They talked about everything but photography, and part of the issue is that photography of all the arts is fairly young – it's only a couple of hundred years old. I would say at this point, we really should have some stuff that makes it more concrete.

If you're studying painting you can find a lot of philosophical material because it's been around longer, that was the problem I saw with photography books. I thought, if I were going to write one, what would that look like? I want it to be very different than anything that's already out – I don't want to rewrite something – I want it to be very unique. So, in Visually Speaking, I talk about the entire process of photography.

Visual language is the overarching theme of the book. Can you describe what that term means to you?

I firmly believe that photography is a legitimate art form. It seems people have questioned that over the entire 200 years it's existed, although less so today. Further than that though, because I have a music background, when you're learning to play jazz and improvise over chord changes, you realize that there's this vocabulary that exists within jazz, and you have to have the discipline to learn that vocabulary to be able to put your own voice into the top of that. It becomes a language just like you and I are talking right now.

We are speaking using subjects, verbs, and all the building blocks that come with talking but we don't think about that when we talk. I don't consciously think about my syntax and make sure my tenses are correct. If we put that idea on top of photography, we can look at it as a form of visual communication – that's where the theme of the book came out – visually speaking.

I wanted to attack it from that angle. What are those building blocks for photography? Those you learn that you can integrate into your mind to the point where you can improvise and they're part of your subconscious.

Everybody is a photographer, in the sense that everyone's got a camera on their phone, and people who are not photographers are still communicating visually. It is a part of our culture today so it's fascinating to look at what became the catalyst for the book.

The book hits on the ingredients and skills needed to make work that matters, or more intentional work while using 'visual language'. Why do you think that this is important?

I'll tell you something funny about this, the whole idea of 'work that matters' is that when I was young, a senior in high school, at the graduation ceremony they'd have speakers and I remember this one guy came in, I think he was a musician working locally, and he came to give us advice before going out into the world to further our knowledge and our talents.

He said, and I thought it was kind of dark at the time, "the world doesn't need any more musicians, doesn't need any more photographers, it doesn't need any more actors, it doesn't need any more writers. It doesn't need any of these things, there's enough out there. And if you choose not to do it, the sun still comes up tomorrow."

That's the harsh reality, but he also said, "What the world does need is more people who have something to say. It needs more positivity. It needs more people who can be inspiring in a direction." I think what he was saying is don't just go be another photographer, really legitimately try to do something that matters not only to other people but to yourself.

What that means to me is that you've got to put your heart and soul into it. For instance, we were talking about books earlier, and your collection is behind you and mine is back there. I can think of my favorite ones and I didn't buy them just because it was a photography book, I bought them because I loved what the photographer had to say and what they were contributing.

I have a wide range of styles of photography that I enjoy and that I like to look at, and those people, to me, are creating work that matters as they're doing something that's speaking to me. I think that's the most important thing people can digest.

How can photographers be more intentional in their practice or approach?

It's going to require that you start looking at photography differently than just shutter speeds and ISO. I made The Artist Series in 2017 a crowdfunded project where I got to photograph this little miniseries of living photographers that I looked up to. I don't think any of them ever talked about what camera they used or about a shutter speed or an f-stop the entire time – except Alexey Titarenko because he does the long exposure.

They're thinking about what their artistic identity is and how to get that across. I think one of the most impressive people I talked to was Laura Wilson who I think is incredible. Laura said, "You got to forget about the stops and the shutter speeds you have to understand all the work that's come before you. See what's been done, how you can fit into that, and then you have something to say". I think that's important.

In the modern world, we are inundated with photographs, many of which are technically perfect. I feel it's more important than ever to establish individual voices and this book will help many people who aren't sure where to start with this. This brings me to the section 'Context' which as you say is often overlooked – why is context an important aspect to consider in photography?

Context has to do with everything we're talking about photography being a visual language. If you take an image of a female torso, it's not a portrait, it's just a body shot that could bring to mind things like Greek sculpture for instance, or fine art. But if you placed the same image in an ad about breast cancer – it has a completely different meaning. Everything has a different meaning depending on how you show it.

It's certainly something that I've been thinking about a lot recently. I've changed my practice over the last couple of years, being especially mindful of context in the way that a viewer experiences the photograph. I think it is often overlooked recently with social media.

That brings up a really good point because it took two years to write this and social media has already drastically changed since I wrote the chapter on Instagram. But you're right especially when you have a fire hose of imagery – I'm sure somebody's done a study about how many photographs the average person sees in one day? Maybe several hundred, right? When you think of billboard advertising, social media, and what comes across on television, the context there is important too.

I think that the problem with social media is that there is more often no context for what an image is. It's a picture of a tree, good luck getting that to communicate to anybody. It makes it hard because you have no context of what that image of the tree means because I just saw an airplane before it and a family picture and then some travel blogger – it will show you things you're not even subscribed to now. So that provides no context other than the fire hose just quick one-second experiences with imaging.

You have a chapter that touches upon legacy; how do you believe an artist's legacy influences their creative work?

That is an interesting point, and again this was inspired by when I did The Artist Series back in 2017, and all of a sudden I was able to talk to William Wegman and Alexey Titarenko. All those artists are aware that they're leaving behind a large body of work that is their legacy and one day when they're not here anymore, leave something positive behind.

I think that's something you start to become more aware of a little bit later in life, I don't think anybody in their 20s is going to be thinking about their legacy necessarily. But when you get 50, you start to think about things a little bit differently and certainly, when I look at somebody like my friend Ralph Gibson, he's 88 now and he's definitely in legacy mode. He's constantly working on the next project, he's always looking for the next payoff, what he can do or say with a camera, or what book he can put out. I get really inspired by that.

It's something that I've been thinking about personally recently as well. It goes back to making work that matters, making work you're proud of leaving behind.

It is, and those are all good things that not only improve you as an artist but hopefully make the world a better place; they make the whole art of photography a better place. Those things are important and it does give you as an artist or as a photographer an opportunity to step up and kind of lead in that sense. Maybe it's an education thing, maybe it's an inspirational thing, but to stand up, make a stance, and say, "Hey, I'm going to create something that is intelligent that has some staying power" – that's what we want more of!

Visually speaking, will now play a part in your legacy... Do you see it as a that?

Good point, I hadn't even thought about that. I mean, you kind of guessed that that's a possibility. The only thing you can control is making the best work possible and as long as you're okay with that if it succeeds that'd be awesome. If it flops I still know I did a good job at the end of the day and I can be proud of what it was and then you move on to the next project.

I know the book is an educational tool, but I do want to make sure we mention your photography in the book – it's beautiful!

Thank you, I appreciate you saying that. One thing I think is important to me, and this is not really in the book, but it's about staying with it and understanding that this is a journey. I took two workshops this year, I did one with Sam Abell and I did another with Arthur Meyerson, and even when I studied with Ralph he couldn't believe that I wanted to do that.

The other workshops had other students attending, and one of the things that makes it difficult is people know who I am when I go, and then they're not sure why I'm there – I'm there to learn!

I don't want to ever stop learning, and I don't want to ever think that I'm at the point where there's something I couldn't get from somebody else in their approach to this medium that we love. That's something that I stress to people all the time is make time for yourself to do those things.

Now I know we touched on how gear isn't the be-all and end-all, but I'd be remiss not to ask: Are you shooting with the same camera consistently now? Have you found what works for you?

I shoot mainly with a Leica, although I still sometimes shoot with a Hasselblad since the XCD came out. The reason why I choose Leica is I really love rangefinder cameras and I wish that in terms of digital cameras, there were more options. I know it's one thing to say, use inexpensive gear and here I'm shooting a Leica these days, but, the more important takeaway is to find what works and stick with it. I think that changing things around a lot does become a little bit of a distraction because you're constantly adjusting.

Even more valuable than camera choices though is your lens choices. When I first started studying with Ralph Gibson, he looked right at me and he said, "Here's the deal, Theodore. You're going to get rid of all those cameras and lenses behind you and I want you to shoot on a 50mm lens and a rangefinder for the next year."

So I paired it down, I took that very seriously, and I only use a 50mm now for my own personal work. I moved to one lens and if you have that opportunity, try it. The 50mm was a kit lens for so long so you don't think it as being very exotic, but look at almost every image Cartier-Breeson made in his entire career – it was on a 50mm lens!

Visually Speaking is a must-have for photographers of all levels, blending practical advice with deeper discussions on legacy and artistic expression. Ted Forbes' ability to educate, whether on screen or in print, is exceptional, and this book is an essential addition to any photographer's library.

Visually Speaking by Ted Forbes is available today in the US for $40 and is available to preorder in the UK for a January release for £25 (Australian pricing to be confirmed) – the perfect holiday gift this year!

A heartfelt thank you to Ted for his generous time and insights in this interview, I could have kept talking about photography with Ted all day, and in actuality, there is a lot of the conversation that unfortunately had to be left on the cutting room floor!

If you haven't checked out The Art of Photography YouTube channel I highly recommend you run, don't walk, as you have countless hours of photography content at your disposal!

You might also like...

If you want to Buy this book! Ted Forbes redefines the how-to photography book with 'Visually Speaking' then you can, or look at all of the best books on photography.