Early on 1 January, gunmen in armoured cars rode up to the entrance of a state prison in the Mexican border city of Ciudad Juarez and opened fire.

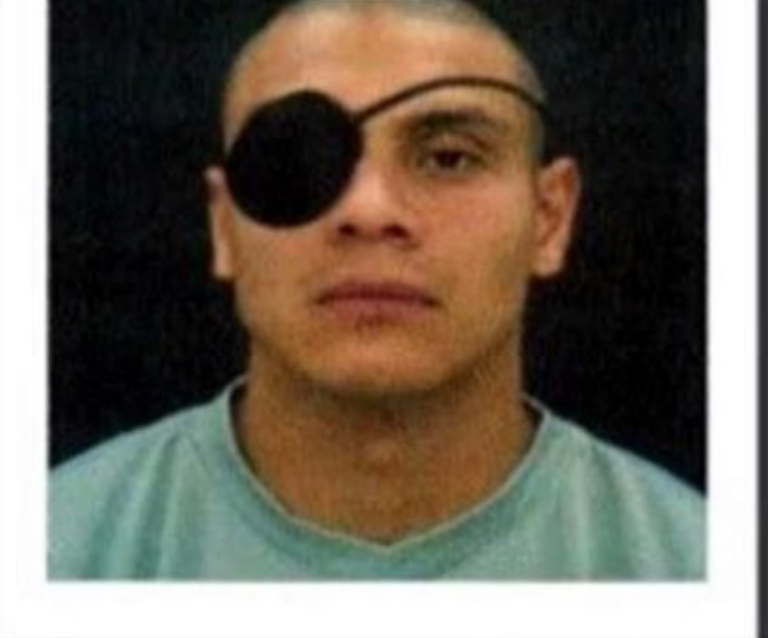

The brazen attack just a few hours into the New Year left 19 dead, including 10 guards, and triggered a mass escape of inmates, including the kingpin Ernesto Alfredo Piñon de la Cruz, also known as “El Neto”, local officials said.

Hundreds of military personnel were flown into the border state of Chihuahua to hunt for the escapees.

And on 5 January, EL Neto, the leader of Los Mexicles, a Ciudad Juarez street gang aligned with the Sinaloa Cartel, was killed in a shootout with police, the State Prosecutor’s Office announced in a press release.

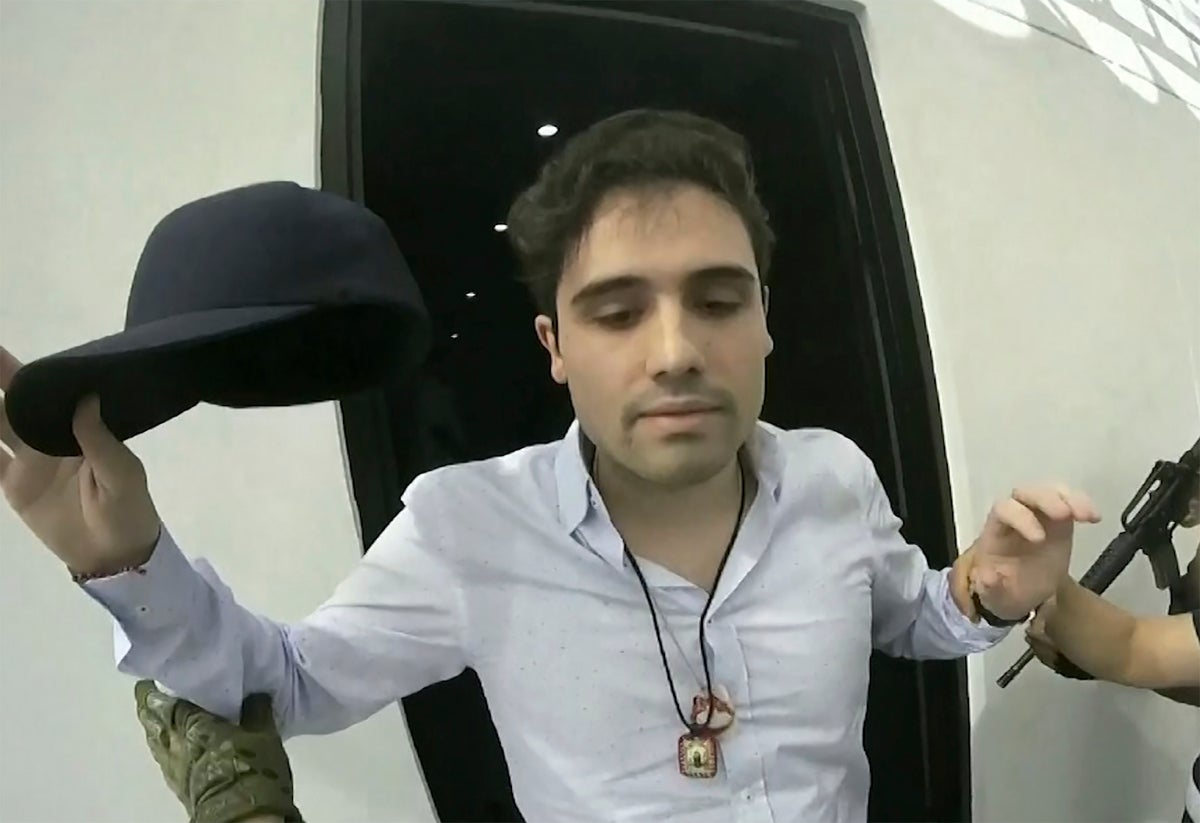

Thursday’s arrest of Ovidio “El Raton” Guzman, son of the former Sinaloa Cartel boss Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, was hailed by Mexican authorities as a major blow to its sprawling drug trafficking empire, whose tentacles spread to every US state.

Defense Minister Luis Cresencio Sandoval confirmed at a news conference on Friday that nineteen suspected gang members and 10 military personnel were killed during Guzman’s arrest, per Reuters. He also said twenty-one other people were arrested during the 5 January operations and there were no reports of any civilian deaths.

Mr Sandoval added that Guzman’s arrest prompted a shootout with gang members; he was later extracted by helicopter from the home where he was caught and flown to Mexico City.

Now held in a maximum security federal prison, Mr Sandoval also said that there would be an enhanced security presence in Sinaloa to protect the public. He said there’d be an additional 1,000 military personnel traveling to the region on Friday.

Caborca Cartel boss Rafael Caro Quintero’s capture last July was similarly vaunted as another high-profile scalp in the war on Mexico’s drug cartels.

But in a country numbed by 16 years of drug-fuelled cartel violence, the arrest or elimination of narco bosses is little cause for celebration.

More often than not, it only brings even more flagrant attacks, as was seen in the Sinaloan state capital Culiacan on Thursday as news of Ovidio Guzman’s arrest spread.

Cartel members hijacked trucks and set them alight, blocking major exits to the city, and fired a volley of shots at a Aeroméxico commercial airliner at the city airport on Thursday.

Video footage showed passengers ducking for cover as bullets hit the plane while it was preparing to depart for Mexico City.

Residents of the city of 800,000 were warned to remain off the streets by officials.

An epidemic of violence

According to the Council on Foreign Relations, more than 360,000 Mexicans have been killed in drug violence since the government employed a more aggressive approach against the cartels in 2006.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador pledged to lower the death toll by taking the military off the streets when he came to power in 2018.

But like his predecessors, Mr Lopez Obrador has increasingly relied on tactical army units to combat the heavily armed cartel members.

Mexico recorded 31,127 violent homicides in 2022 alone, or roughly 86 per day, according to figures from the Mexican Government.

On a single weekend in December, a judge was murdered in Zacatecas state, five people were killed in a bar shootout in the Pacific coast city of Acapulco, and members of the Sinaloa cartel attempted a prison break in the central city of Cieneguillas.

Addressing the violence at a press conference in late December, Mr Lopez Obrado said his administration had “stopped the upward spiral”.

“It took us time because, like I said, of the dynamic of increased violence. But (from 2020), it started going down and we propose to reduce it further.”

Politicians, law enforcement, members of the judiciary, journalists and activists are often deliberately targeted by the cartels.

At least 91 politicians, including 36 candidates, were murdered in the lead up to national elections held in June 2021.

Women are especially at risk. Femicide cases increased by 145 per cent between 2015 and 2019, according to the Los Angeles Times.

As crime increases, the shortcomings of the country’s judicial system means that 95 per cent of violent crime goes unpunished, according to a 2021 study by the think tank México Evalúa.

High-profile cases such as the April 2022 murder of 18-year-old law student Debanhi Escobar highlighted frustrations about a lack of progress in prosecuting violent crime.

Once confined to drug manufacturing regions and border states as cartels fought over valuable drug routes into the US, the violence has spread into every corner of the country.

The US State Department warns against all travel to six Mexican states; Colima, Guerrero, Michoacan, Sinaloa Tamaulipas and Zacatecas, due to the danger of crime and kidnapping.

The failed war on the Mexico’s drug cartels

In 2006, then Mexican president Felipe Calderon deployed thousands of troops in a military crackdown on the drug cartels, in what’s come to be known as start of the “Mexican drug wars”.

After initial success in detaining the leaders of several cartels, the violence quickly escalated as cartels splintered into new and more violent groups.

Official estimates put the number of drug-related homicides in the years between 2006 and 2012, when Enrique Peña Nieto was elected president, at around 50,000. The true number was believed to be more than double that figure.

Mr Peña Nieto pursued the policy of all out war on Mexico’s drug cartels, leading to tens of thousands of deaths each year.

The US has provided billions of dollars in weapons and training and to modernise Mexico’s security forces, reform its judicial system, and fund development projects, the Council on Foreign Relations notes.

After Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman was rearrested in 2016 and extradited to the United States in 2017, it created a power vacuum in the Sinaloa Cartel led to further waves of violence, the Los Angeles Times reported.

Officials in the state of Sinaloa warned residents to brace for increased violence after the arrest of his son Ovidio Guzman.