Ambushed and captured by Vietnamese communist guerillas, French journalist Georges Petwhenier was one of the few Westerners to see Viet Cong fighters in their element as they fought US soldiers and their South Vietnamese allies during the Vietnam war. He described their jungle sanctuary in an article in The New York Times published in 1964.

“In comparison with the Vietnamese jungle, the bayous of [US state] Louisiana are like an English garden. Tormented by mosquitoes, ants and ticks, one must hack painfully through with a machete, crawl here, climb there and ford streams infested by leeches. It is a living hell,” he wrote.

North Vietnamese war artists painted a very different picture of the country’s jungles, and communists, however, as illustrated in a project titled “Vietnam: The Art of War”.

The project was curated by researchers who had comprehensive access to archives at the Witness Collection, one of the world’s largest collections of Vietnamese art. Aiming to document the world-shaking conflict from a Vietnamese perspective, it incorporates war art from the country collected over more than 30 years.

Northern troops’ mastery of the natural environment contributed greatly to their successful fight for a unified and independent Vietnam.

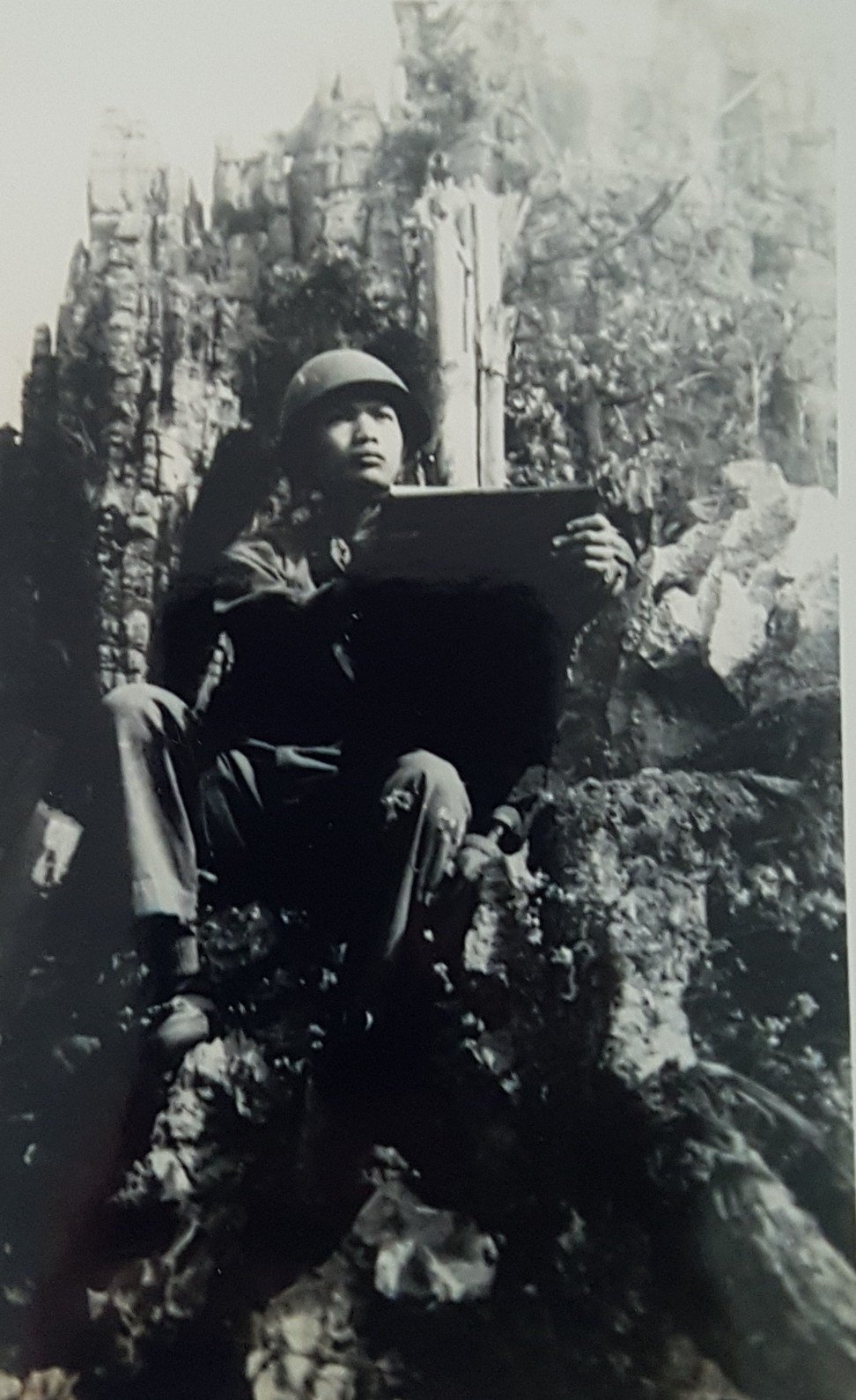

While marching in the mountains of Quang Tri province in 1972, war artist Nguyen Duc Tho came across a jungle-based team providing food to anti-aircraft artillery units stationed nearby. Continually threatened by American B52 bombers, the troops needed two vital elements: camouflage and shelter. The jungle provided – in the form of a gigantic, hollowed-out dead tree.

“When cooking for the soldiers, they had to be very careful to avoid letting enemy aircraft detect smoke from the stoves,” Tho says. “The tree’s inside was all rotten, but on the outside, leaves were still growing green. So the hollow tree was an ideal place for them.”

The tree not only acted as a camouflaged storage area and shelter but as a funnel to disperse smoke from the team’s campsite.

Available food – edible, nutritious and even delicious – was another crucial difference between the lives of US and North Vietnamese forces. American GIs and their allies in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam were often forced to scrounge for food and could have trouble finding enough to eat because supply chains had been cut. They became ill and got thinner by the day. North Vietnamese war artists, meanwhile, remember feasting on the land’s bounty.

Tho, who was in artillery regiments throughout his career and finally attached to the Hanoi 361 Air Defence Division before the war ended, painted many scenes where producing and cooking food took centre stage.

From the soldiers who had once been farmers growing vegetables in the thin soil between air defence systems in Hai Phong, to troops on the Ho Chi Minh trail cooking for the Tet festival – Vietnam’s Lunar New Year – Tho’s images are a record of North Vietnamese resourcefulness.

“In the Truong Son mountain range, soldiers still made banh chung [rice cakes] and slaughtered pigs,” Tho says. “They also made pork sausages just as they once did to celebrate Tet at home.”

Artists tell of comfort cooking even in the dense jungle wilderness. At a medical station at the mouth of a cave in the Truong Son forest, Bui Quang Anh was able to eat “delicious food beyond our imagination”.

“They caught crabs in the forest, in streams, in caves, to make crab banh da cua [rice paper soup],” Anh says. “They also used rice paper to make spring rolls with a few vegetables and meat. How could we eat something so delicious in the forest like that?”

Anh spent a large part of his career documenting the Ho Chi Minh trail, following the hidden supply route from Hanoi through Laos and into South Vietnam’s Tay Ninh province. A lifeline for soldiers, materials, supplies and equipment, the trail was often used by the North Vietnamese to transport a rarely considered resource: fuel for vehicles.

“It took a lot of work for vehicles that transported gasoline to travel, and they were also frequently attacked by aircraft and set on fire,” Anh says. “So at the time, the head of the general department of logistics came up with a solution, which was using underground pipelines to transport gasoline to the south, to the end of the Ho Chi Minh trail. All the pipes made up a length of over 1,000 kilometres [620 miles].”

Anh saw the trail as more than a logistical lifeline for the troops. He witnessed a country continuing to live and thrive, rather than just grinding out an existence. Grand caves provided natural amphitheatres for musical performances. Jungle clearings were used as serene settings for dance troupes. A wedding was organised, attended by tribal elders, military representatives and a symphony orchestra.

“One time, on a moonlit night near a station, an art troupe who had just come back from Cuba started singing the songs they had learned there, such as Guantanamera and Besame Mucho,” Anh says. “When they sang Besame Mucho, men and women danced the rumba together in the middle of Truong Son forest. Perhaps, in this world, it is rare to see such a passionate dance of love in the middle of a forest, under the crape myrtle trees and a bright moon, with the rumbling sounds of bombs from afar.”

Literature and arts belong to the same front, on which you are fighters. Like other fighters, you, in the artistic field, have your own responsibilities - Revolutionary leader Ho Chi Minh in a 1951 letter

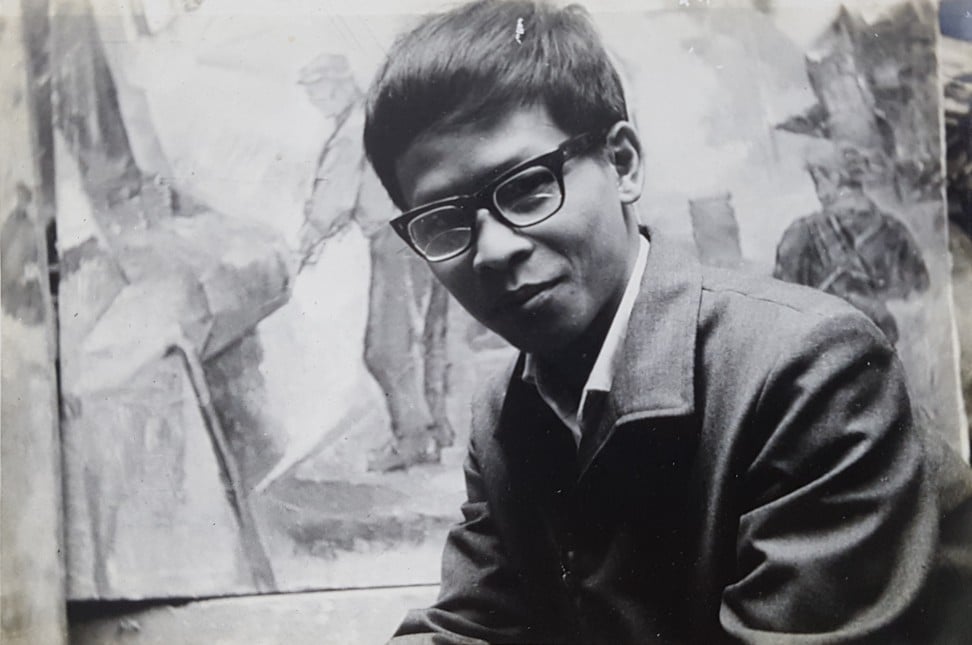

Besides recording intimate details of troops’ lives in the North Vietnamese army, war artists were well placed to comment on realities that often escaped their Western adversaries during the conflict.

Pham Thanh Tam, an artist and journalist, was already a veteran reporter of the First Indochina War (1946-54) against colonial France when he found himself looking out at US marines hunkered down at Khe Sanh Combat Base.

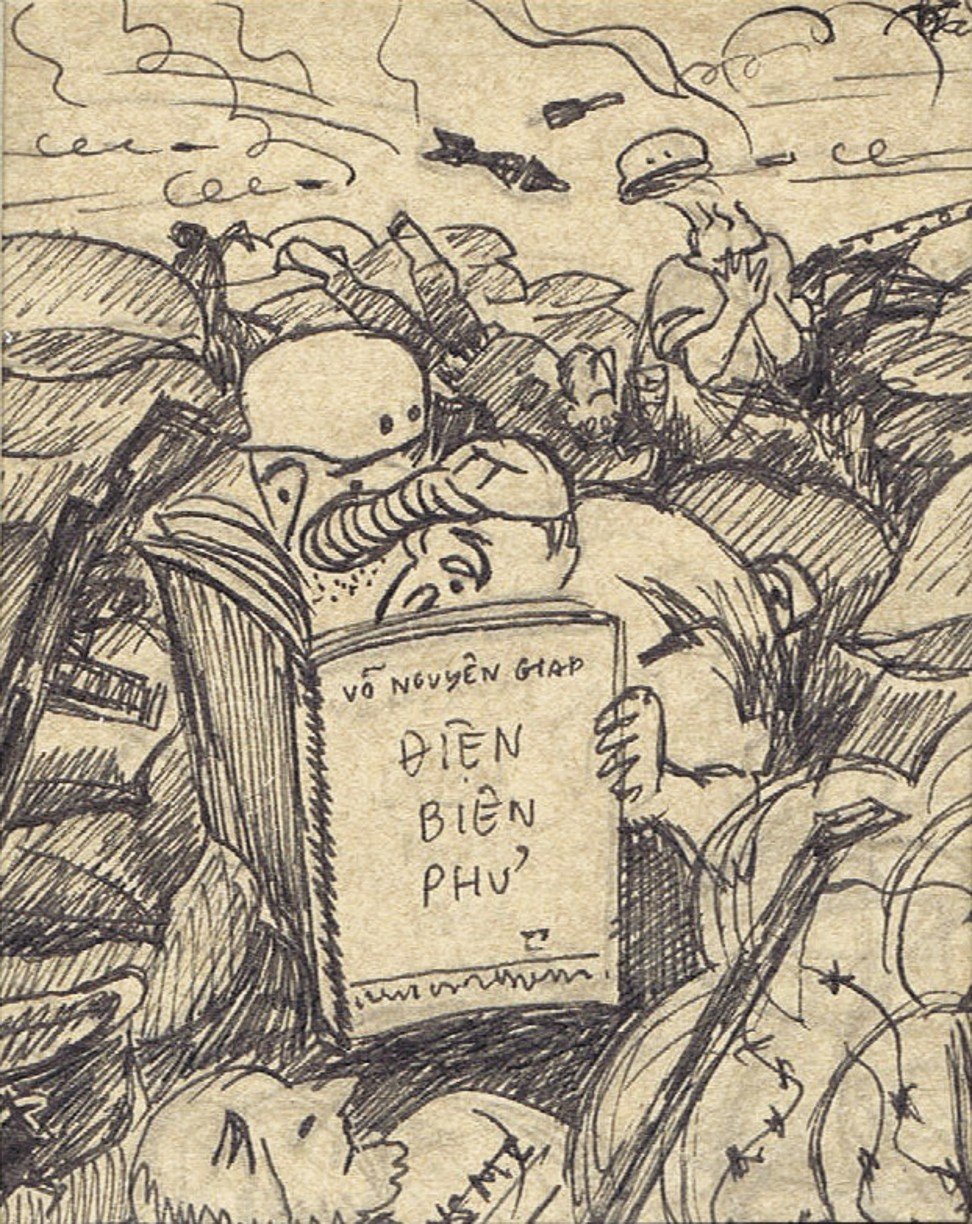

Remembering his experience of the battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, Tam saw parallels in Khe Sanh. Building and protection of the base at Khe Sanh had come under scrutiny by baffled US observers because the site lacked any real strategic advantage. The surrounding hills made it difficult and risky to defend. With US military leaders increasingly doubting the base’s usefulness during the 1968 Tet Offensive, Tam saw it as an eerie repetition of French intransigence in past conflicts.

In the decisive Dien Bien Phu siege, which paved the way for the French withdrawal from Vietnam, Viet Minh artillery units laid siege to French soldiers and finally routed them.

“It was just as fierce,” Tam says, comparing the two battles. “That battlefield [Khe Sanh] was one where bomb craters were everywhere. So that battlefield was called the ‘B52 bomb bag’.”

His art developed from that point. “From there I also found that in addition to realistic depictions, I should write and compose types of artworks that were satirical and critical.”

His cartoon of US marines reading from the handbook “written” by famed Vietnamese general Vo Nguyen Giap about Dien Bien Phu conveys the sense of the “screeching” bombs, but it is also a comic representation of American confusion at the time – a precise take on the travesty of Khe Sanh, one of the longest battles of the Vietnam war.

In contrast with Western commentary on the conflict, Vietnamese war artists provide fundamental insights into the spirit of the Vietnamese. Far from the biased interpretation of red-eyed bogeymen haunting the land, they portray Vietnamese communists as intelligent, resourceful, determined and expressive individuals.

As documentarians, North Vietnamese war artists played a vital role in their country’s pivotal conflict. For revolutionary leader Ho Chi Minh’s dream of unification, war artists were as important as soldiers taking up arms.

“Literature and arts belong to the same front, on which you are fighters,” the revered leader declared in a 1951 letter written from the Democratic Republic of Vietnam headquarters in the Viet Bac region of North Vietnam. “Like other fighters, you, in the artistic field, have your own responsibilities.”