A veteran from the HMAS Melbourne and HMAS Voyager collision on February 10, 1964 that killed 82 people believes changes to floodlighting on the aircraft carrier caused Australia's worst peacetime disaster.

There were two royal commissions into the accident that occurred when aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne struck HMAS Voyager, tearing the destroyer in two.

The cause remains unknown although human errors were identified.

John Werner, 77, who worked on HMAS Melbourne in weapons electronics-gunnery systems, has spoken about the crash for the first time at a Port Lincoln Returned Services League event commemorating the 110th anniversary of the Royal Australian Navy.

He was the duty electrician that night and set up floodlighting on the aircraft carrier to light the deck and island section for the aircraft.

HMAS Melbourne had undergone a re-fit and he noticed the floodlights now had red filters.

"I thought 'things have changed'. In the past they'd been just normal white floodlights," Mr Werner said.

"After thinking about it and talking to a couple of other guys on the Melbourne, I understood that the bridge on the Voyager mistook these for the red steaming light of the Melbourne and cut across what she thought was the stern, which in fact was the bow.

"At least one of the red filtered floodlights was facing to starboard — it overshone the green navigation light, being mistaken on Voyager's bridge as the port navigation light," Mr Werner said.

Two books written

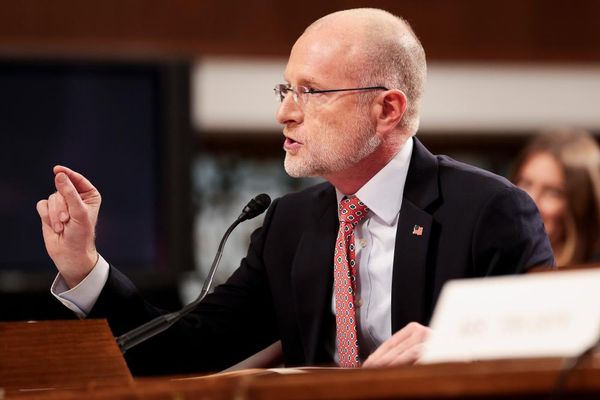

Ex-RAN officer and author of two books on the collision Professor Tom Frame said all the crew on the bridge of the Voyager died except one sailor who was reading while wearing headphones, so the cause of the accident would never be known.

Professor Frame said the most likely cause was a communication error.

"I believe the initiating cause for the collision was that a signal from Melbourne was inaccurately relayed within Voyager, so Voyager believed that Melbourne was turning around to the west when in fact Melbourne did no such thing, she continued on basically a northerly course," he said.

"Melbourne stayed straight, Voyager turned, Voyager then placed itself under the bow of Melbourne."

Professor Frame said the stern light and the port side light, which was also red, were easy to see.

He said the Voyager crew should have been watching the Melbourne closely.

'Don't create waves'

Mr Werner said he signed an affidavit stating he thought the red lights had been mistaken on Voyager's bridge to be the port steaming light of Melbourne but was told his evidence was suppressed and not to talk about it.

"I particularly remember them saying not to create waves," Mr Werner said.

"I love the navy and I decided I would never do anything to hurt it."

Two royal commissions

Professor Frame said some information would have been dealt with in-camera for security reasons.

"It was potentially misleading, the new floodlighting that was being trialled, potentially," he said.

"But the royal commission was aware of it, one, and secondly came to the view, as I came to the view, that it wasn't the cause of the collision.

"The navy in one sense did a pretty poor job of explaining to its own people … why they thought it occurred and so it led people like John and others to think that the evidence that they presented was not given the recognition that it deserved."

Mr Werner is speaking out now because he has post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from his career that only surfaced when he retired.

He remembers helping in the rescue mission aboard the HMAS Melbourne, operating the winch to bring aboard the lifeboats.

"I didn't see anyone in the water but I did note what super-heated steam can do to a human body – some of the injuries the people had, I don't want to think about it," he said.

Mr Werner was reassigned to the navy's smallest boat, the HMAS Teal, a minesweeper operating north of Australia, and experienced trauma from conflict in Borneo before being reposted to the HMAS Melbourne.

"I can't remember what I did on the Melbourne the second time – it's blocked out of my memory. I can't remember, so it must have affected me some way," he said.

Game changer

Professor Frame said the Melbourne had 906 people on board that night and many of them felt that somehow if they had acted differently then things might have been different.

He said it was a game changer for the navy.

"Well, sometimes that's the worst thing you can do to people."

Professor Frame said Mr Werner and many others were left in the dark as to the significance of their evidence and whether it was really taken into account, because of secrecy and "just treating junior sailors as an expendable commodity".

Mr Werner was active in the navy for nine years and then worked on several projects as a civilian for the navy, air force and Department of Defence specialising in electronic warfare, weapons, and weapons systems.