While Earth and Venus are approximately the same size, and both lose heat at about the same rate, the internal mechanisms that drive Earth’s geologic processes differ from its neighbor. It is these Venusian geologic processes that a team of researchers led by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and the California Institute of Technology hopes to learn more about as they discuss both the cooling mechanisms of Venus and the potential processes behind it.

The geologic processes that occur on Earth are primarily due to our planet having tectonic plates that are in constant motion from the heat escaping the core of the planet, which then rises through the mantle to the lithosphere, or the rigid outer rocky layer, that surrounds it. Once this heat is lost to space, the uppermost region of the mantle cools, while the ongoing mantle convection moves and shifts the currently known 15 to 20 tectonic plates that make up the lithosphere. These tectonic processes are a big reason why the Earth’s surface is constantly being reshaped. Venus, on the other hand, does not possess tectonic plates, so scientists have been puzzled as to how the planet loses heat and reshapes its surface.

“For so long, we’ve been locked into this idea that Venus’ lithosphere is stagnant and thick, but our view is now evolving,” said Dr. Suzanne Smrekar, who is a senior research scientist at NASA JPL, and lead author of the study.

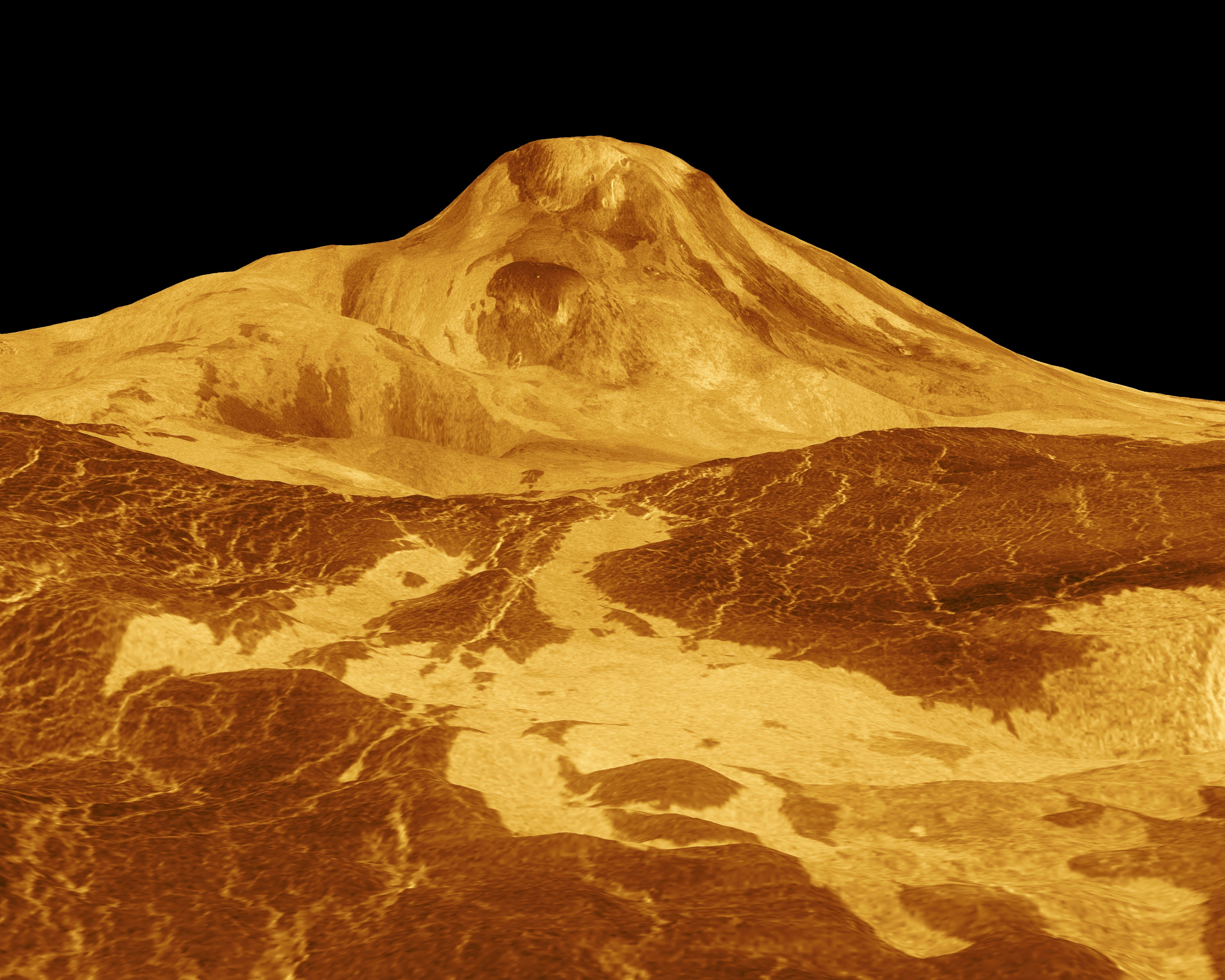

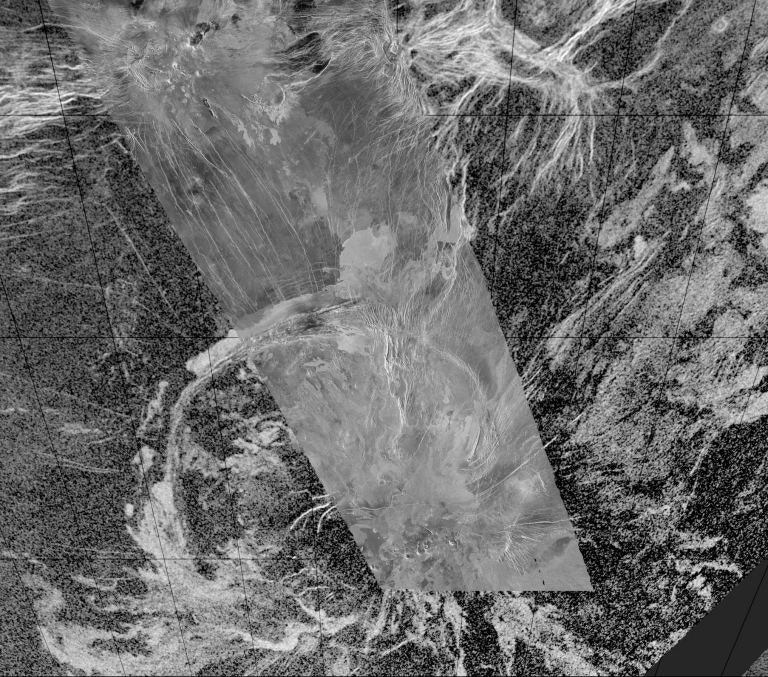

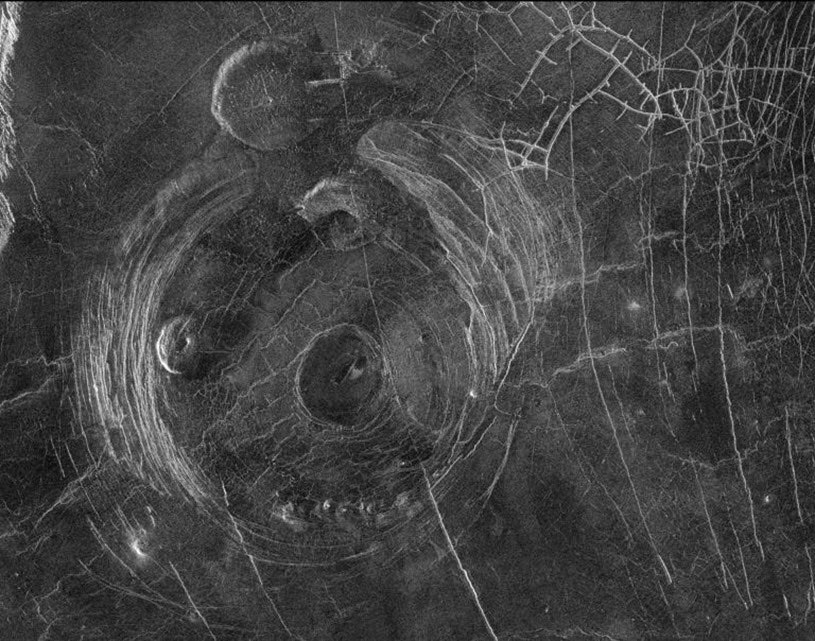

For the study, the researchers examined radar images from NASA’s Magellan mission taken in the early 1990s depicting quasi-circular geological features on Venus’ surface known as coronae. The reason why the images were taken using radar is that Venus’ atmosphere is so thick that normal images taken in the visual spectrum are unable to penetrate Venus’ thick, cloudy atmosphere.

Upon taking measurements of 65 previously unstudied coronae within the Magellan images and calculating the lithosphere’s thickness around them, the researchers found these coronae form and exist where Venus’ lithosphere is the thinnest. Using computer models, they found the lithosphere around each corona is approximately 11 kilometers (7 miles) thick, which turns out to be much thinner than suggested by previous studies. The researchers also suggest the coronae could be geologically active since these areas exhibit a greater average heat flow than Earth.

“While Venus doesn’t have Earth-style tectonics, these regions of thin lithosphere appear to be allowing significant amounts of heat to escape, similar to areas where new tectonic plates form on Earth’s seafloor,” Dr. Smrekar explains.

It is this greater heat flow that might also help scientists better understand the behavior of the lithosphere on ancient Earth, as well.

“What’s interesting is that Venus provides a window into the past to help us better understand how Earth may have looked over 2.5 billion years ago,” said Dr. Smrekar, who is also the principal investigator of NASA’s upcoming Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, And Spectroscopy (VERITAS) mission, which is currently scheduled to launch no earlier than 2027. “It’s in a state that is predicted to occur before a planet forms tectonic plates.”

Launched from the Space Shuttle Atlantis in May 1989, Magellan arrived at Venus in August 1990 and is considered to be one of the most successful deep space missions ever. Despite this, Magellan’s data consists of low resolution and large margins of error, so VERTIAS will essentially act as Magellan 2.0 by producing three-dimensional global maps of Venus using a state-of-the-art synthetic aperture radar, along with learning more about the surface composition with a near-infrared spectrometer.

But the exterior of Venus won’t be the only location being studied, as VERITAS will study the planet’s interior by examining its gravitational field. Altogether, VERITAS will paint scientists a greater picture of both ancient and present geologic processes on our twin-sized and mysterious neighbor.

“VERITAS will be an orbiting geologist, able to pinpoint where these active areas are and better resolve local variations in lithospheric thickness. We’ll even be able to catch the lithosphere in the act of deforming,” explains Dr. Smrekar. “We’ll determine if volcanism really is making the lithosphere ‘squishy’ enough to lose as much heat as Earth or if Venus has more mysteries in store.”

Another Venus mission of importance will be NASA’s DAVINCI mission, whose objective will be to plunge through the Venusian atmosphere and examine its composition in greater detail than ever before.

What new insights will we learn from Venus and its geologic processes in the coming years and decades? Only time will tell, and this is why we use science!

This article was originally published on Universe Today by Laurence Tognetti. Read the original article here.