Makeshift blindfolds, rusted manacles, and messages of despair scratched into the walls of solitary confinement cells by inmates using olive stones.

These are the signs of “life” left in the haunted corridors of the prison in the Republican Guard Compound in Damascus: a notorious and previously closed-off location in the Syrian capital.

Clinging to a hill overlooking the city, the sprawling complex and prison is, according to US diplomats and intelligence officials, one of the most likely locations where the regime of Bashar al-Assad detained Austin Tice, the longest-held American journalist in history.

The former US Marine was abducted in government-controlled areas while reporting on Syria’s civil war in 2012 and is among a “handful” of Americans who remain missing, including psychotherapist Majd Kamalmaz, who vanished in 2017.

The US believes Tice was still alive right up until the overthrow of Assad, whose administration spent decades forcibly disappearing, torturing and murdering people. In many cases, the evidence was destroyed – with US officials saying that included the use of dissolving vats of acid and cremating remains.

And so, every site that Tice and others may be or have been must be searched thoroughly and quickly.

An FBI forensic team has visited the guard compound to scout for clues, including documenting English phrases scratched into the walls, says special presidential envoy for hostage affairs Roger Carstens, who personally joined the search on a recent trip to Damascus that he called “thorough but not exhaustive”.

“More work needs to be done on that specific site [the Republican Guard Compound] alone. There are many more sites in different physical locations that must be investigated,” he says back at his office in Washington DC, holding a map of at least 11 locations that require a proper search.

This is difficult in the immediate chaotic aftermath of the fall of Assad, when thousands of people descended on these areas looking for any information about their loved ones – among them, possibly regime figures who were also looking to remove their files.

The US is being assisted by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the Islamist rebel group that led the stunning overthrow of Assad.

“One of my greatest concerns is that every day, evidence disappears, is damaged, or is lost. And so, it will be unable to be used to either find Austin or prosecute those who may have had a hand in his detention,” Carstens says.

“Even in my short time at one detention facility, I saw what I would characterise as hundreds of thousands of pieces of paper and other types of documentation that would have been helpful to sort through.”

He adds that computer hard drives and CCTV footage looked to be missing.

Right now, the compound, like other sensitive buildings, is manned by rebels wielding Kalashnikovs who take us around. Their main job is to protect the document vaults stuffed ceiling-high with papers, ID cards, and passports: evidence of those who vanished and – crucially – the officials who made them disappear.

“It’s bizarre to be here – feeling joyful in this place of terror,” says one of the rebels, who declines to give his name, while the spray of gunfire and the boom of explosions sound in the background: rebel efforts to beat back looters.

The fighter spent years battling the Assad regime before being tasked by the new interim government with guarding the precious cache. For him, it’s personal – his cousin is among the missing.

“It’s a huge task. We need international help finding the missing and working out what crimes were committed here. We need international courts to prosecute people responsible who fled. We need to bring them back to answer questions. We need answers.”

After 12 years, Austin Tice is the longest-held US journalist in history

Like so many people in Syria, Tice was detained and held incommunicado – vanishing almost without a trace. In late May 2012, the former Marine Corps captain, Georgetown law student and rookie freelance journalist ducked under a fence on the Turkish-Syrian border and joined a group of Free Syrian Army rebels. He began filing stories for McClatchy, and later for The Washington Post. He also appeared on BBC Radio and CBS News.

After nearly three months in the country, he headed for Beirut to take a break, but while driving towards the Lebanese border, Tice was detained in a government-controlled area. Missing for 12 years, Tice is now the longest-held American journalist in history.

There has only been one solid proof of life – a video released in 2012. Since then, Carstens says the US has had credible reports that Tice could still be alive and has been held in regime prisons, military and air force intelligence branches, private homes, and security directorates. The Independent visited seven of the known sites, including the Republican Guard Compound.

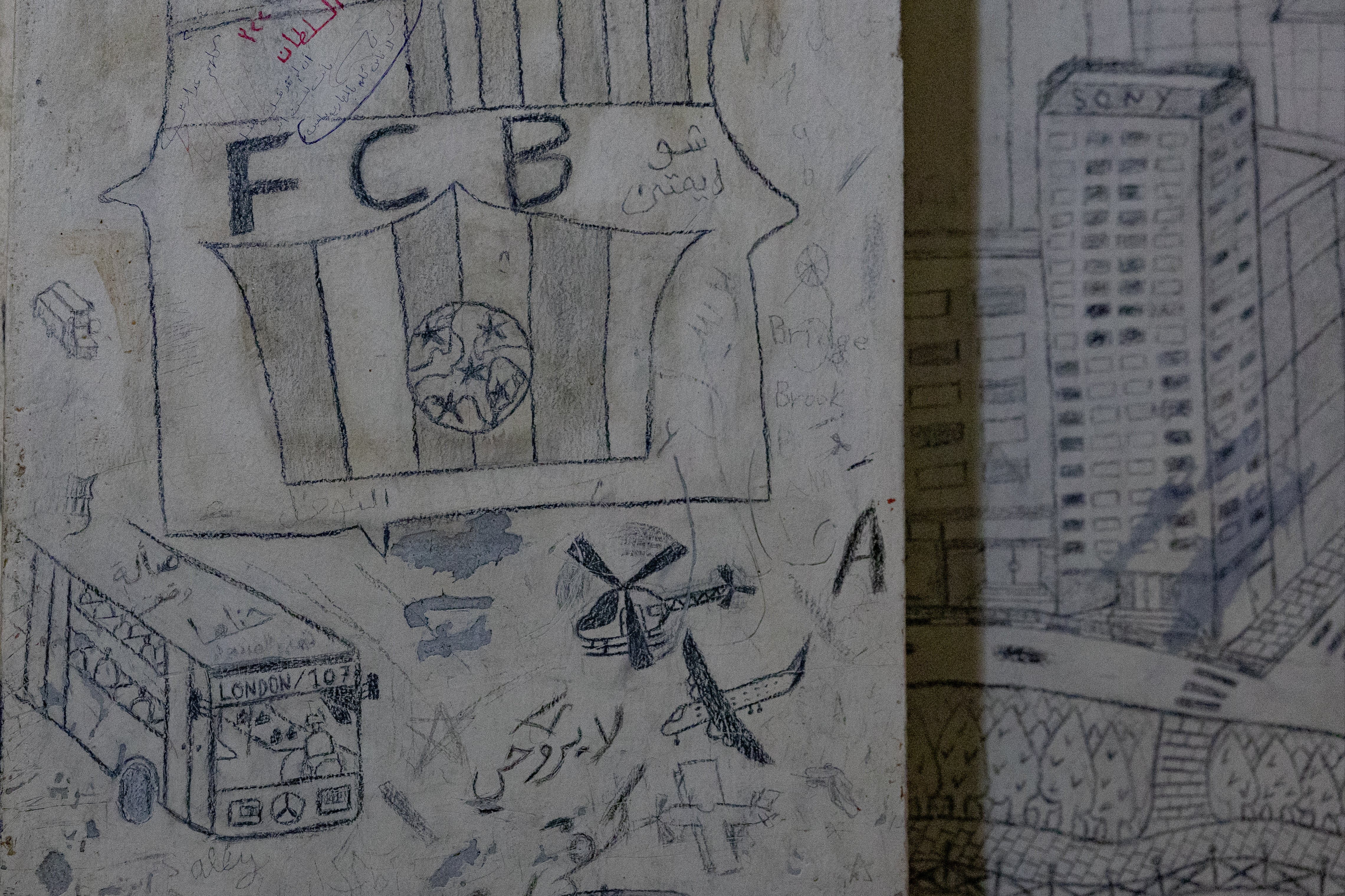

At these compounds, there was a bewildering array of evidence pointed to foreigners being held there, including detailed detainee registration files, testimonies of ex-detainees who described Western inmates, walls scribbled with English-language lessons, and drawings of scenes from Europe and the US.

In the military intelligence directorate, also in Damascus, one cell is covered in a huge mural of a specific London bus that goes to Edgware station and what looks like a scene from New York.

But nothing specifically indicating Tice.

That said, many people still believe he is alive, including the Hostage Aid Worldwide organisation. Its chief Nizar Zakka has said that not only has there never been any proof that Tice is dead, but there was evidence he was alive as late as January.

Zakka said Assad most likely kept Tice in Syria as a potential bargaining chip. US president Joe Biden said on 8 December that his administration believed Tice was alive and was committed to bringing him home, though he also acknowledged that “we have no direct evidence” of his status.

The Independent has reached out to his family but is yet to receive a reply.

There are also concerns Tice may have been taken out of Syria – via the port city of Latakia to Tehran or Russia – although investigators have seen nothing on radars.

The problem is that Syria is a “black box”, given the secretive nature of the Assad regime, warns Carstens, who was appointed to the envoy role in 2020 and is one of the few political appointees President Biden elected to keep in place.

“We had a hard time determining whether the reports we received were fallacious, motivated by money, or mislabelled by names or geography. And that made this problem incredibly frustrating,” Carstens says.

“The bottom line is that Syria tended to be a black box, which tended to frustrate intelligence and law enforcement officials, as well as members of the diplomatic community.”

At the heart of it, Carstens speaks of the “dichotomy” of a brutal regime that would painstakingly document the atrocities it committed, atrocities seen in the images taken by the military photographer and defector codenamed Caesar, who photographed 11,000 bodies of detainees showing signs of torture, illness, and starvation. But on the other hand, bodies would vanish without a trace.

“There are people that the regime held who might have been of such importance – or it was so embarrassing to have had something go wrong with them – that they were willing to forgo their compulsive need to document the disposal of that person. For example, someone dies of cardiac arrest under torture. That body disappears, that file disappears,” Carstens explains.

In fact, there was a “timeline” in terms of the way Assad would operate. He says, chillingly, that the regime began cremating bodies at the end of 2014, and then started putting bodies in acid vats from around 2015.

Family of Majd Kamalmaz fear he has disappeared without trace

This grim erasure is something that Maryam Kamalmaz, the daughter of Majd Kamalmaz, is all too familiar with.

Majd, a Syrian-American psychotherapist from Virginia, was detained at a temporary checkpoint in Damascus in 2017. He had been visiting a relative with cancer and exploring the possibility of setting up a non-profit to support people who had experienced trauma.

US officials from across eight different agencies would eventually sit the family down to tell them they believed he had passed away at some point in detention. But there is no evidence of what happened, why he was held, or where.

“He could be one of the ones that were burned. That’s what I understood,” Maryam says. “Making it nearly impossible to even find any trace of him.”

She describes the agony of not knowing, a pain compounded by fleeting moments of hope. Images of families breaking into prisons and finding relatives presumed dead for years, but still alive, have inspired her to keep searching. Then there was a sighting of an ex-detainee who bore a resemblance to her father, but it turned out not to be him.

“It renewed our hope that maybe, maybe there was some confusion, and he could still be alive,” Maryam says. “So it really ignited our emotions.

“I was going through all the videos and pictures and the list of names, trying to find him anywhere. We had family members on the ground outside prisons, trying to see if they could find him. But nothing came out of it, unfortunately.”

For families like the Kamalmazes, the Assad regime’s methods of erasure make it almost impossible to trace what happened to their loved ones.

A Syrian intelligence official who fled Syria and defected told the family that there was a special red line under her father’s name – which Maryam says they later found out means “get rid of this individual without leaving any trace or evidence”.

Her father never had a trial, nor is there information about any charges or his whereabouts. “It’s clear they got rid of anything to show that they had him. That way, we can’t – neither we nor the American government – blame them for anything,” she adds.

Syria’s White Helmets search for hidden cells underground

Three storeys underground, in the bowels of the General Intelligence Directorate in a suburb of Damascus, the White Helmets, Syrian first responders, are searching for hidden cells. Armed with specially trained sniffer dogs, torches, and cameras, they are looking for any sign of a dungeon yet to be opened.

This multi-building complex is one of the other places where Tice, and possibly even Kamalmaz, may have been held. The documentation rooms have been ransacked, with paperwork strewn across the floor like fallout.

The walls of the cells are tattooed with writing, indicating the diverse nationalities once detained here – everything from lessons in Turkish and Russian to song lyrics in English.

“We have formed several search and rescue teams after pleas from families urging us to find people in places like Saydna [a notorious prison],” says one of the White Helmet rescuers, explaining how they spent three days inspecting “every corner of the prison,” from electrical wires to sewage systems, but found nothing.

“Two hours ago, we were informed that there is a prison in the General Intelligence Directorate that has not yet been opened. We immediately sent our teams, including police dog units and search and rescue teams, to this location,” he adds.

This is happening across the capital and other cities – desperate searches for missing people, including at the infamous Palestine Branch just a few kilometres away. It was a heavily guarded and notorious prison complex.

Part torched, part flooded, in the gloom we meet Ahmed, 24, a Palestinian former detainee who was sent here as a teenager and spent four years behind bars in a cell filled with foreigners, including a German aid worker.

He describes being tortured with electricity, beaten with plastic hoses, forced into a tyre and beaten (a torture method known as “dulab”), and strapped to the so-called “flying carpet,” where people are secured face-up on a foldable board, and one end is brought up to meet the other.

“And in this hallway, they would slaughter prisoners – the blood would flow here,” he says, pointing to a wall with stains down it. Next to it is a cell. “The foreign prisoners were kept here.”

Ahmed was detained here, then at the security branch where the White Helmets are now searching, and finally at Saydnaya, around 20 miles (30km) north of Damascus. Saydnaya, often called Syria’s “slaughterhouse prison,” is described by Amnesty International as the “final resting place” for many political detainees.

Ahmed explains how constantly moving detainees around made it impossible for families to locate them. Those who didn’t survive would be buried in mass graves, many of which are only now being discovered, he adds.

‘The world needs to help us record these war crimes’ – Maryam

At the site of one mass grave in Qutayfah, outside the capital, Mouaz Moustafa, head of the Syrian Emergency Task Force, which has spent years tracking the missing and the dead, urges the international community to step up and help interim authorities examine these graves and begin the gruelling process of getting answers – not only for missing Americans but also for Syrians.

“How do you take fast DNA samples so that people wandering the streets of Damascus looking for their mothers, fathers, sons and daughters can have closure, knowing that they’re gone?” he asks in desperation, looking out over the field which could hold as many as tens of thousands of bodies.

“I’ve been looking for my uncle. So this is my story. And it’s everyone’s. And it’s every human being who has a heart. Because if we let things like this happen, it’s not just about Syria.

“It means you can be a dictator, use chemical weapons and cluster bombs, and torture to death in order to hold on to power.”

Maryam, whose family is stuck in the worst kind of limbo, echoes the same plea. She urges the world to send professionals and teams to Syria while the evidence is still there.

“I think it’s really important that the international world understands how huge this is and how crucial it is to have professionals sent to Syria to help in every shape and form – to preserve these documents and to find out what happened to these family members that disappeared,” she says. This would allow families even a small measure of closure and accountability.

Carstens acknowledges that more needs to be done and vows that the US government is continuing the search for Tice and other Americans, in tandem with Syria’s new Islamist administration.

For the families left behind – including those of Tice and Kamalmaz – all they can do is keep up the “desperate search” for years and years.

“It is ruthless and heartless to do this to families – to never acknowledge our loved ones, to make them disappear, to put us through this emotional rollercoaster of not knowing anything,” says Maryam.

The uncertainty and lack of closure have left Maryam’s family in what she describes as “indescribable pain”.

“It’s been a very, very difficult and emotional time,” she says. “My request to the US officials was simple: find out what happened and try to bring him home, no matter what.”