Val Kilmer, who has died at the age of 65, spent his career at war with himself. Fame was a burden. Success was a chore. He masked his face as Batman, disguised it in The Saint, surrounded it with a halo of unruly curls as Jim Morrison. In True Romance, he is Christian Slater’s id – a devil on his shoulder who speaks and moves like Elvis – and mostly off-camera. You see his neck. His chest. His face through a blurry reflection in a mirror. What was a Val Kilmer role without a degree of subterfuge to it?

But it meant that when you did see him – once he dropped the pout, the mystery and the brooding stoicism – it would feel revelatory. Think back tothe crushing devastation of his last scene in Heat, when he realises he’ll never see his wife again. His smile droops, his eyes are suddenly moist. Or what about that gum-smacking grin of his in Top Gun. Or the heartwarming vulnerability of his return in Top Gun: Maverick 36 years later, his voice dimmed by his real-life throat cancer, but that twinkle intact, that cocky swagger, those sharp cheekbones that could still do damage.

What a strange movie star Val Kilmer was. He was handsome, charismatic, difficult. Always a bit of a kook. He filmed himself on a camcorder constantly, footage of which made up the bulk of a documentary about him released in 2021 called Val. Appropriately, Val was more of a mosaic of Kilmer than an excavation of his psyche. Even in a film about his life, he maintained his strange obscurity: a man with peculiar creative tastes blessed (cursed?) with the looks of a God; a Christian Scientist in his private life; an ex of Cher’s; an actor who seemed to get the most artistic pleasure out of the one-man show he wrote, directed and starred in, as the folksy humourist Mark Twain. Ticket holders would enter each venue Kilmer played to find the actor reclining in the stalls in old-age makeup, white fright wig and mustache. He’d make his way up to the stage, riffing on faith, mortality, the act of acting. Over the course of his 90-minute monologue, he’d slowly remove his prosthetics until he once again resembled Val Kilmer.

He seemed, in the best and worst senses of the word, exhausting. He was a Method actor and mischief-maker, both nice ways of saying that a litany of filmmakers couldn’t stand him. On the set of 1995’s Batman Forever, one of his ill-fated attempts at name-above-the-title film stardom, he would show up late covered in blankets, clash with the crew, and say his lines so quietly that no one could hear them. “The two weeks where he didn’t speak to me [were] bliss,” its director Joel Schumacher once said. On The Island of Dr Moreau a year later, actors were so incensed by Kilmer’s surly behaviour that they’d ring up their agents begging to quit the film. Marlon Brando reportedly threw Kilmer’s phone in a bush and told him that he’d confused the size of his salary for the size of his talent. “I don’t like Val Kilmer, I don’t like his work ethic, and I don’t want to be associated with him ever again,” said the film’s director John Frankenheimer.

Kilmer tended to gloss over these incidents. He’d speak obtusely about them, with language so flowery that it’d take you a minute to realise he’d said nothing at all. “In an unflinching attempt to empower directors, actors and other collaborators to honour the truth and essence of each project, an attempt to breathe Suzukian life into a myriad of Hollywood moments, I had been deemed difficult and alienated the head of every major studio,” he wrote in his 2020 memoir.

Kilmer was a Juilliard-trained actor crammed into films he, early on at least, deemed beneath him. “I was insecure and competitive when I was younger,” he said in 2017. “I wanted to be loved for my Hamlet while I waited in line for my decaf, not [hear] ‘Hey, Iceman!’” He turned down Francis Ford Coppola’s The Outsiders – which made stars of Tom Cruise, Patrick Swayze and Matt Dillon – to appear in a Broadway play, and spent years disliking Top Gun as he worried it glorified the military.

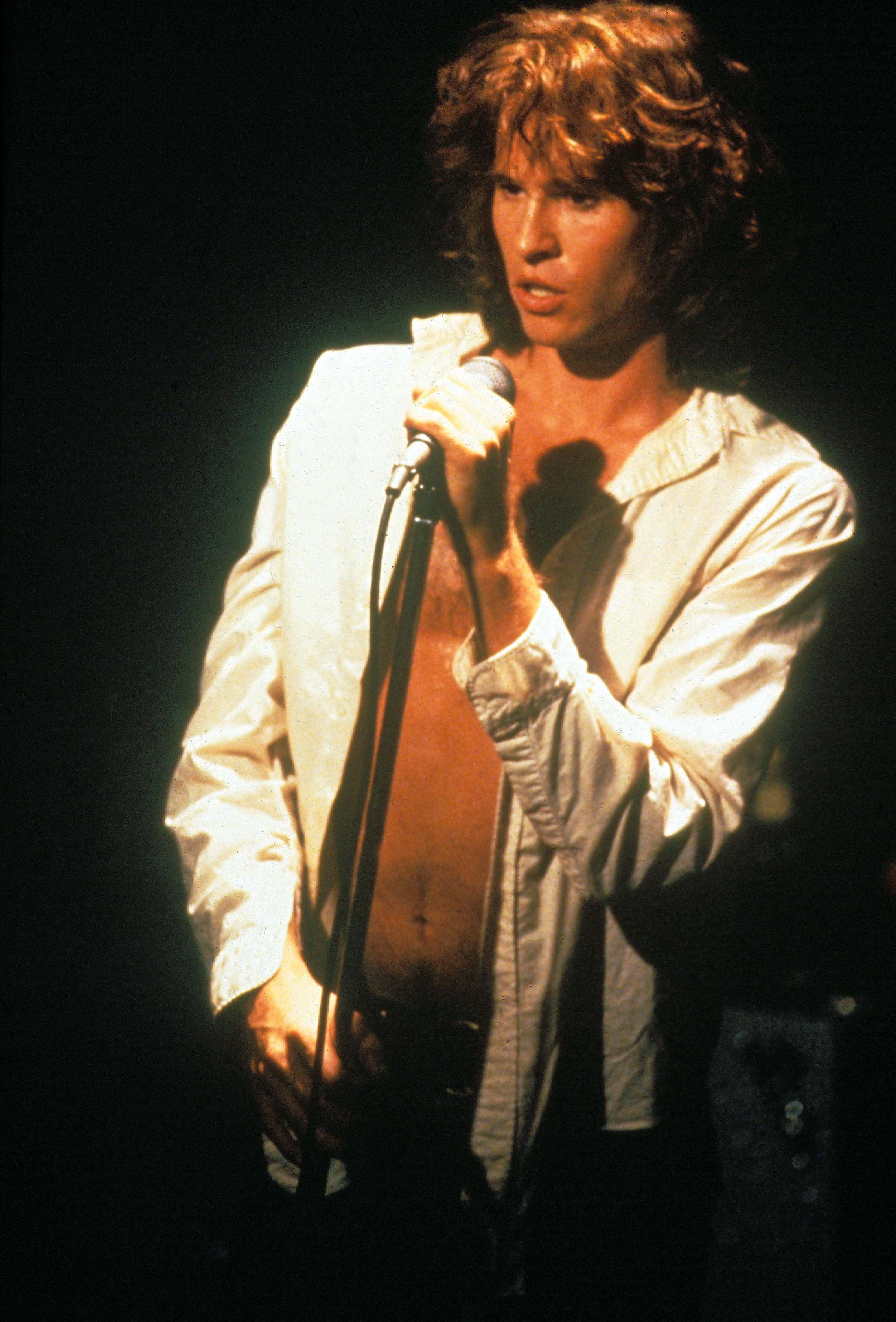

Many of the films he desperately wanted to star in – Goodfellas and Full Metal Jacket, most notably – were ones he didn’t get. Those he fought for and did get were directed by men who seemed to match his odd mix of slick, cocksure madness. When Oliver Stone dithered over casting him in The Doors, Kilmer spent thousands of dollars of his own money to fund an elaborate, multi-scene audition reel in full Jim Morrison drag that he shot in his Laurel Canyon home. Stone gave him the part. Ultimately, he was so convincing as Morrison – dropping to his exact weight and learning to sing 50 songs by The Doors despite only needing to sing 15 for the film – that the band’s surviving members admitted that they couldn’t tell the difference between Morrison and Kilmer’s singing voices.

It wasn’t that Kilmer eventually found a sanctuary in serious independent films – most of his career was spent, by and large, inside the studio system – but the erratic quality of his career did prove a blessing in disguise. He was an actor who always seemed to be making comebacks, the ambiguity of his movie stardom meaning that every sudden reappearance felt like an arrival. His performance as the porn star John Holmes in 2003’s Wonderland drew raves (“It proves once again what a marvellous actor we have in Val Kilmer,” went critic John Patterson), likewise when he played a gay detective in 2005’s neo-noir comedy Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. “Kilmer displays a rich comedic sensibility he should deploy more often,” went The Hollywood Reporter. It was easy to forget about Kilmer, then see him in something and spend the immediate aftermath questioning why he wasn’t in absolutely everything. In a review of Terrence Malick’s wacky 2017 Hollywood tapestry Song to Song, Variety critic Peter Debruge wrote: “There’s a very funny bit with Val Kilmer playing a rebellious old rocker who takes a chainsaw to his speakers mid-set – why not make a movie about him?”

Despite his restlessness and penchant for chaos, Kilmer was undeniably talented, a man whose artistic and existential battles played out on screen, on set, and concurrent with his enormous, unasked-for fame. For many who worked with him, the noise was ultimately worth it – if only for those glimpses of something extraordinary once it had quieted down.

“I didn’t say Val was difficult to work with, I said he was psychotic,” Joel Schumacher joked in 2020. “But he was a fabulous Batman.”