In the final weeks of his presidency, Joe Biden, has agreed to give Ukraine a further hand in shaping the land war against the Russians. On October 17, he granted permission for Ukraine’s armed forces to use the long-range Atacms missiles against targets in Russia, a move that prompted the UK to do the same. Ukraine has reacted by using both countries’ missiles in attacks on Russian soil, prompting a stern warning from Moscow.

The Russian president, Vladimir Putin, subsequently signed off on changes to Russia’s nuclear doctrine, which makes it easier for Russia to launch a first-strike.

But it is Biden’s decision to send anti-personnel mines (APLs) to Ukraine to help it shore up its defences against the relentless Russian offensive that has sparked controversy. These landmines are reported to be “non-persistent” – meaning they can be set to be active for a limited amount of time and deactivate once their batteries fail.

But in an era when the use of anti-personnel mines carries such a taboo – 164 countries (but not the US or Russia) are signatories to the Ottowa Convention (also known as the mine ban treaty) that prohibits the use, stockpiling or transfer of APLs – the move has been condemned by international humanitarian organisations.

Details have yet to emerge as to what sort of landmines have been promised to Ukraine by the US except that they are non-persistent APLs. The US has several APL and non-persistent landmine systems as well as mixed APL and anti-tank (AT) systems.

Dedicated APL systems are pursuit-denial munitions and area-denial artillery munitions (Adam). As an example of a mixed AT and APL system, the M87 (Volcano) is a mine-laying system that uses prepackaged mine canisters, which can contain multiple APL or AT mines, or both, which are dispersed over a wide area when ejected from the canister. Other militaries that have not signed the Ottawa Convention also use this system.

The mines supplied by the US are most likely to be part of the Adam system. This would allow for quick deployment in the face of rapidly advancing Russian troops and for tactical remote deployments as Ukrainian troops are forced back. Like the Volcano system, they also can be remotely ejected quickly to help shape the battle.

Controversy over landmines

The US has been condemned by many humanitarian organisations for this change in policy. While it is not bound by the Ottawa Convention, the US has been keen to limit the role of landmines beyond defence of South Korea. And many governments and charitable organisations are now engaged in the task of mine clearance around the world. But, according to recent Nato estimates, there are still at least 110 million landmines littering 70 countries.

The concern now is that the willingness of the US to give Ukraine APLs means that the taboo on deploying landmines in conflict zones is being rolled back.

Ukraine has said that they will only be used in non-residential areas and on the frontlines of the war. But the concern is not as much with the actual weapons system in Ukraine: the mines are non-persistent and will not leave a lasting threat. The worry is that this appears to be a very public display of landmines as legitimate weapons of war.

It’s worth noting that Ukraine is already one of the most heavily mined countries in the world. Russian forces have used 13 types of landmines to limit the advance of Ukrainian forces. The Russian use of landmines in the east of Ukraine began after the 2014 invasion of Crimea and several regions.

The World Bank reported last year that demining Ukraine would cost US$37.4 billion (£29.6 billion). But the Russian deployments of landmines in Ukraine have not received the same pushback by the international community that the US has. This is largely because the US has been an active diplomatic player in the campaign for the limitation of their use in modern conflicts.

In 2014, the Obama administration introduced restrictions on the use of APLs anywhere apart from in defence of South Korea. These were rescinded by Donald Trump in 2020. In 2022, the Biden administration announced it was reimposing restrictions on APLs to bring the US in line with the Ottowa Convention anywhere outside the Korean peninsula.

Russian advantage

Setting aside the humanitarian argument against deploying APLs, the changing nature of the war now means that they are an appropriate and potentially effective weapon for Ukraine to deploy at this stage. Ukraine’s successful use of drones against Russian armoured vehicles bringing troops and supplies to the moving frontlines has meant that the invading troops have been ordered to ditch their vehicles and walk to their forward positions.

Groups of soldiers are much more able to stay hidden from Ukrainian drone crews, and traditional anti-tank grenades are less effective on infantry moving on foot. And as more Russian troops are travelling on foot, AT landmines also become less effective in forcing them into Ukrainian fire lines.

So, in order to deal with the rise in infantry pressing the offensive, Ukraine has asked for these mines, which have the potential to allow them a degree more control over what has become an inexorable Russian advance.

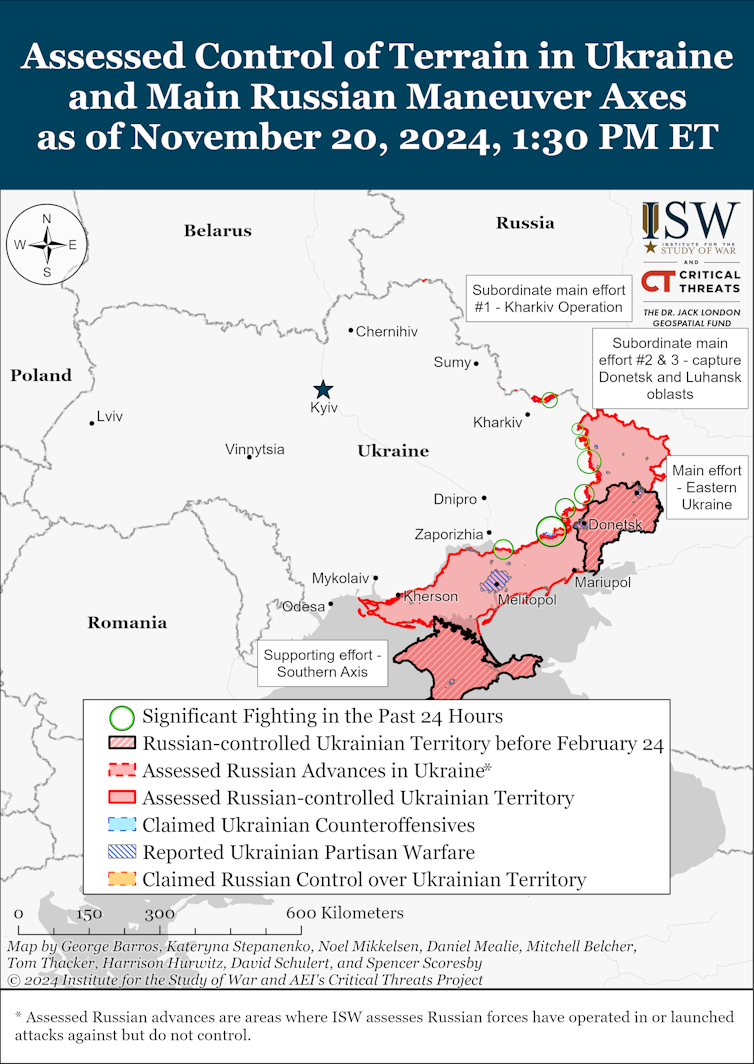

The Russian advance continues to gather pace. Both Ukraine and Russia know that there will be a time when a question over land and peace will be brought to the negotiating table – so, as a result, the drive to hold and take territory is likely to intensify.

David J Galbreath has received funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council, the Economic and Social Research Council and most recently the Australian Army.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.