There may be some previously "under the rug" issues with the United State's CHIPS Act, a $280 billion subsidy package aiming to strengthen the country's semiconductor manufacturing infrastructure. Namely, the recent gridlock regarding raising the debt ceiling limit has already sparked a reduction in part of the Act's funding allocation, which could spell more challenging times for high-tech funding allocation further down the road.

The CHIPS Act outlines a plan to inject $280 billion in funding to increase domestic semiconductor manufacturing capability in the US. This investment aims chiefly to insulate the United States' supply of chips in case of increased geopolitical tension surrounding Taiwan, home to all-powerful TSMC - whose research and manufacturing expertise make it a prime target for absorption.

Luckily, the $52 billion injection in direct subsidies to chip manufacturers (such as Intel) is already funded, so initial work on laying the foundations for US-based foundries can start. This is the quickest way for the US to reduce its dependence on Taiwan's manufacturing capabilities.

But out of the $280 billion, a large portion of it ($170 billion) requires yearly appropriation by Congress - meaning its allocation depends on whether more funding can be borrowed through the raise in the debt ceiling limit. That leaves it at will of the negotiations between Republicans and Democrats.

This $170 billion is split between the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy and is intended to fund workforce development, STEM education, and research and development over the next three years. And there've already been cuts in this year's planned injections: the National Science Foundation (NSF) received $9.87 billion out of a maximum of $11.9 billion, and the Department of Energy (DoE) received $8.1 billion out of a maximum $8.9 billion.

We've also seen a turning of the tides where tech companies have been triggering layoffs - if companies are cutting workforce costs, there's less need to introduce new workers into the field. But research and development are fundamental in a competitive scene where the leading edge, the ability to churn out chips with the highest number of performant transistors, attracts the most significant returns. Just ask TSMC.

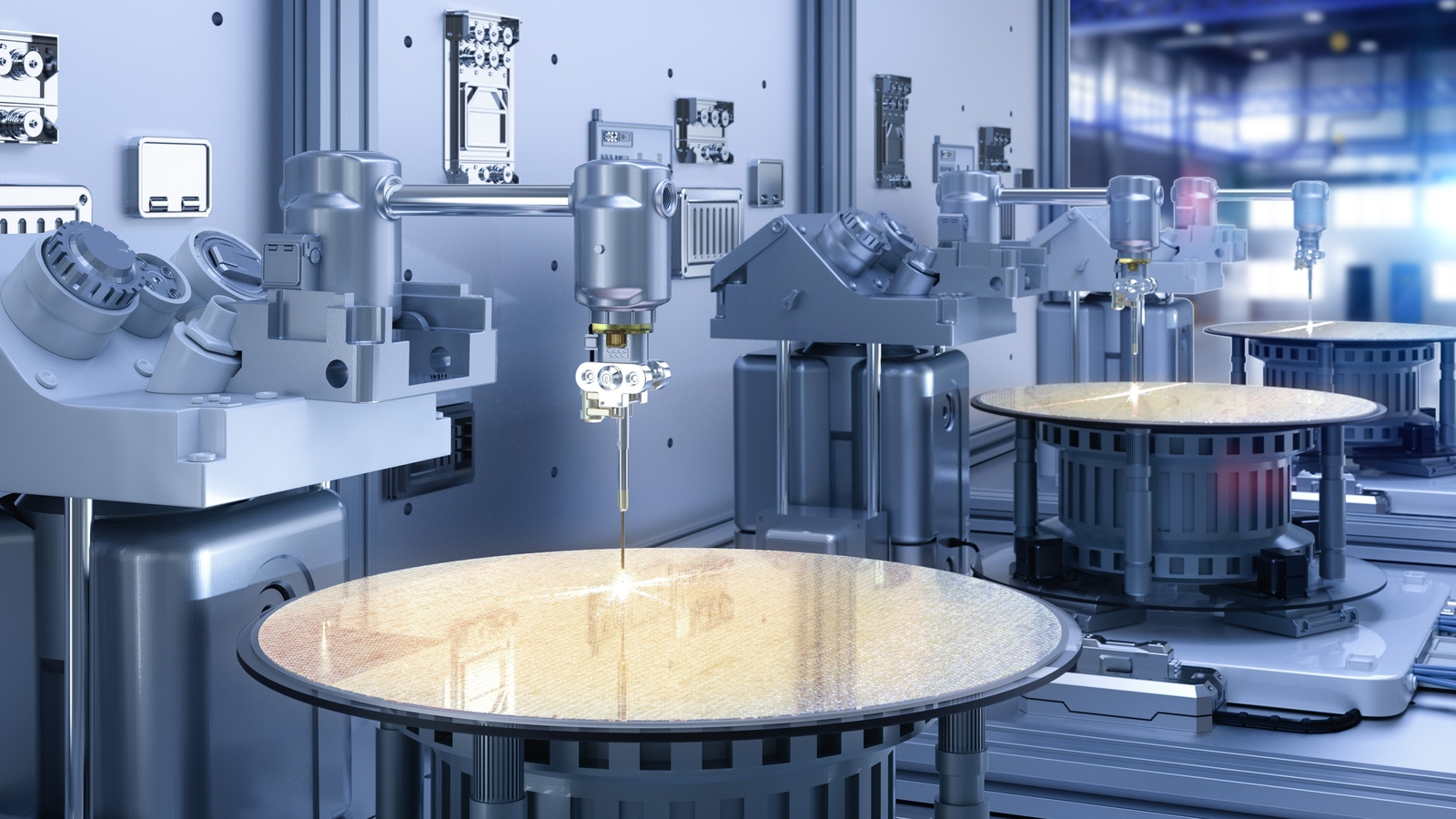

Yes, the first round of funding for foundries "Made in the US" has been secured. But as Intel, TSMC, AMD, and any other company that's meddled with semiconductor design and manufacturing knows, this field isn't a 100-meter sprint. It's the 800-meter tactical racing equivalent to a multi-year fab construction. All while adapting design processes and tooling so that everything - including supply chains and human resources - fit so right that the well-oiled machine of semiconductor manufacturing can output adequate amounts of wafers - never mind yields - come the day of the opening ceremony.

Unfortunately, neither Democrats nor Republicans function like a semiconductor factory; their plans are fickler and more prone to error. It remains to be seen whether there'll be enough motivation to keep funding flowing to where it's best applied.