In the summer of 1991, Jane's Addiction's Perry Farrell launched the inaugural Lollapalooza festival, America's first travelling 'alternative music' roadshow, which would, in time, be credited for helping lay the groundwork for propelling 'underground' rock into the mainstream. Farrell would later claim that it was a visit to England's Reading festival which planted the seed for Lollapalooza in his brain, but The Cult's Ian Astbury might argue that the inspiration for what became one of America's most influential festival brands lay rather closer to Farrell's back door.

“I was sitting in the front of the tour bus one day with my notebook, thinking, Wouldn’t it be great if I could take the records in my collection and see a festival with some of the best acts? Why not an event where you could see all this great music?”

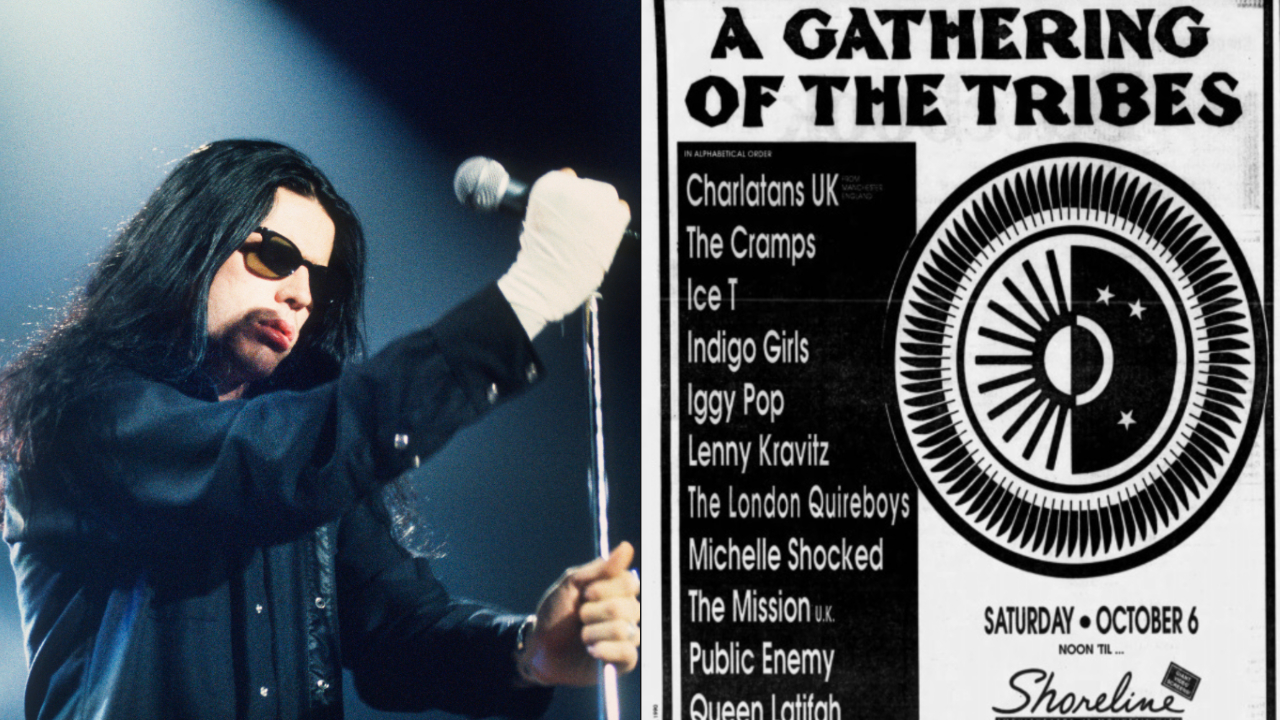

This was what the then-28-year-old singer told the LA Times in 1990, ahead of the two-city Californian event he had curated to take place on October 6 at the Shoreline Amphitheatre in the Bay Area, and October 7 at the Pacific Amphitheatre in Costa Mesa.

“I thought it would be great to put a diverse bill together and see if it could happen and introduce all the segregate groups to each other," Astbury explained, admitting that he himself didn't initially believe that such a concept might have legs in a market where genre formatting traditionally kept artists firmly in their lanes. Putting the bill together, perhaps inevitably, proved tricky, with some of Astbury's 'first draft' picks - Guns N' Roses, Living Colour, Tracy Chapman unavailable due to prior commitments - and not everyone in the industry welcoming the singer's sideways move into festival booking.

Interviewed for the Jane's Addiction biography Whores, Astbury told writer/promoter Brendan Mullen, “There was a bit of an agency war over the bands who wanted to be involved. Oddly enough, the guy who wouldn't let his bands be on the bill was at the forefront of Lollapalooza. A premiere alternative rock agency got wind of the festival and they had so much envy because they weren't involved, that they tried to destroy it.”

“I had Iggy Pop calling me at home saying, I can't do the festival.' I said, Why not? he said, 'People have said it's going to be a failure, it's not going to be good for my career.' I said, We need you. Don't listen to their shit.”

Viewed from a 2024 perspective, the 14-band bill which Astbury assembled actually sounds much more impressive than it did it in 1990, with Pop, Soundgarden, Public Enemy, The Cramps, The Mission, Ice-T, The Charlatans, Queen Latifah, The Quireboys (or The London Quireboys as they were known in the US) and ex-Sex Pistol Steve Jones among the attractions. Notably, there was no spot on the line-up for Astbury's own band, which he explained by telling the LA Times, “I didn’t want people to think we were using this to boost our career.”

It would be fair to say that the Gathering Of The Tribes festival didn't set the world alight. It probably didn't help that the bill's most high-profile act, Public Enemy, didn't show in Costa Mesa, with Astbury, Queen Latifah and Ice-T all telling the crowd that Chuck D's group were absent due to pressure from local authorities, something the local police insisted that they had no knowledge of. Around 10,000 people showed up to each show, and while the event didn't cause huge ripples in the industry, it was generally received warmly: “Chalk up one small blow for diversity, if not for overriding musical excellence,” wrote the reviewer from the LA Times.

Ultimately though, Astbury reckoned that he lost $50,000 of his own money on the weekender, and plans to resurrect the idea as a travelling festival the following year - with an excellent bill touted to include Primus, King's X, Fishbone, Steve Earle and more - was abandoned when the finances involved did not add up.

That summer, however, Lollapalooza launched with Jane's Addiction, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Ice-T, Nine Inch Nails, Living Colour, Rollins Band and more, and the idea of an emerging 'Alternative Nation' was talked up by Perry Farrell. Meanwhile, to his understandable annoyance, Ian Astbury's trailblazing weekender was consigned to being a mere historical footnote.

“I was ripped off,” Astbury told Brendan Mullen bluntly. “I never got the credit. We didn't do it for the money, we did it for the community.”

Watch Astbury talking to MTV about the festival below: