As universities roar back to life with renewed expectations, students head to institutions that will shape their lives both now and in the future.

At university, students are presented with various opportunities to participate in the governance of these communities. They may be asked to answer surveys, vote or — if they are confident enough — run for elected positions in a student union or as a class representative.

As researchers interested in exploring novel approaches to practising democracy in organizations, we see this type of participation as crucial.

It can enable diverse groups of students to interact, tackle important issues, hold universities accountable and develop their capacities to be confident, engaged and thoughtful participants in civic life.

Pressing aspirations

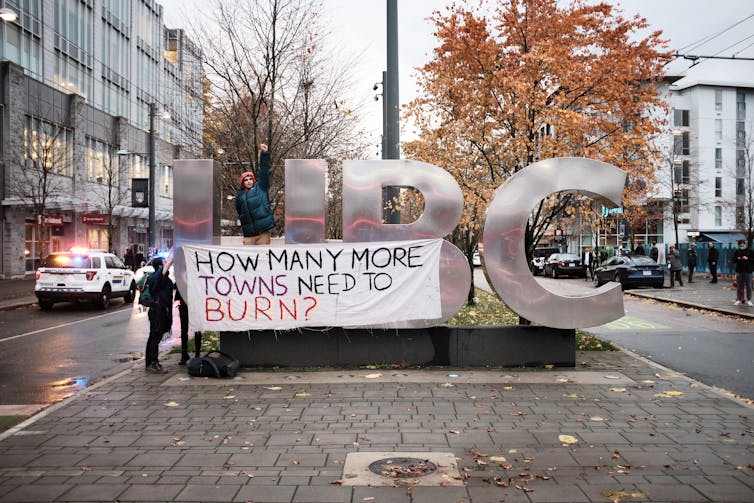

These aspirations are all the more pressing in light of democracy’s current challenges — like low voter turnout, distrust and polarization.

Universities have a role in revitalizing democracy. Yet, despite the merits of contemporary approaches to student participation in university governance, these tend to face major deficiencies.

We argue that universities should look to democratic innovations seen with initiatives like Climate Assembly UK.

Looking to democratic innovations

Climate Assembly UK was initiated by a group of select committees of the United Kingdom’s House of Commons. Organizers selected the 108 members — made up of everyday citizens — through a democratic lottery.

The use of a lottery brought together a diverse group of voices, representative of the demographic profile of the U.K., and distributed opportunities for civic engagement more equitably across the population.

Over six weekends, these citizens heard from a range of experts and stakeholders and deliberated together with the support of independent facilitators. They developed and presented recommendations spanning topics including consumption, travel and greenhouse gas removals.

Climate Assembly UK is just one example of a deliberative “mini-public,” whose use has been proliferating globally.

They’ve been used to tackle issues like transportation planning, child care, democratic expression and the impact of digital technologies and genetic testing.

Problems go beyond headlines

In the world of university student politics, recent years in Canada saw reporting about spending scandals, disqualified candidates, threatened sanctions over polarizing decisions and the wholesale replacement of a student federation over misconduct allegations.

Reporting about these challenges also makes headlines in the United States and the U.K.

Our recent research finds such headlines are symptomatic of wider problems.

Shortcomings are less about people and more about the approaches used to involve them. Traditional approaches ultimately fail to foster universities’ capacity to have inclusive and thoughtful discussion shape decision-making — their “deliberative capacity.” After all, in any democracy, people expect more than simply staying out of scandal.

Limitations of surveys, voting, running for office

While surveys are easy to administer, they limit student voice to top-of-the-head responses. They provide information isolated from background context and collect views unevenly across demographics.

Like voting — which regularly suffers from poor turnout — surveys also offer limited opportunity for students to develop civic skills and capacities like critical thinking and communication.

For those few students ready to overcome barriers to running for, and winning, elected roles, more intensive experiences await. But these experiences are often in unsupported environments that foster conflictual or self-interested approaches to shared concerns.

Yet another question is the extent to which these elected students reflect the diversity of the student body.

More deliberative student influence

Some universities are beginning to experiment with mini-publics. Our own universities experimented with a “Students’ Jury” on pandemic learning and a “Students’ Dialogue” on youth participation in democracy and civil political discourse.

The London School of Economics’ Students’ Union recently used this approach to redesign its democratic structures.

Our research concludes that, if done well, the key features of mini-publics provide a compelling means of more inclusive, deliberative student influence and should be used much more broadly.

A student mini-public could be commissioned by either university or student union leadership. The gathering size can be tailored — from a jury of 12 students to an assembly of 150. Mini-publics can be purposefully combined with existing opportunities like representation on boards of directors to maximize impact.

Through mini-publics, students could address a wide range of important and potentially controversial issues that university communities can act on, like universities’ strategies for tackling climate change or campus free speech or student housing.

Tackling a student housing strategy

A university seeking to co-develop its student housing strategy might convene a student mini-public of 36 students to tackle the issue.

Using a democratic lottery would ensure the mini-public reflects the diversity of the student body based on characteristics like gender, academic year, race, international versus domestic enrolment status, income and current housing situation.

Students would access balanced and comprehensive briefing materials on topics like the university’s current land use policies, environmental strategies and finances. They would learn from experts like urban planners and researchers, as well as stakeholders like residence services staff, local developers and other students.

Read more: Housing is both a human right and a profitable asset, and that's the problem

Their recommendations would be shared not only with relevant decision-makers, but also the broader student body to help inform conversations in the student newspaper or social media, in dining halls or in the student pub.

Such an approach would give every student an equal chance to contribute and develop, help guard against the distortions of the self-selecting “usual suspects,” and facilitate a student voice that reflects the diversity of backgrounds, personalities and needs in the student body.

Thoughtful, representative decisions

Built-in learning, facilitation and deliberation means that decisions are informed and shaped by others’ perspectives.

This not only means more thoughtful and representative decisions, but a greater diversity of students accessing meaningful, deliberative civic education.

While there is still a lot to learn about incorporating student mini-publics, they are an exciting and realistic prospect.

It’s crucial universities take innovative steps to foster more inclusive, deliberative approaches while educating for the kind of democracy we want.

The research project this article is based on was partially funded by Simon Pek's President's Chair award.

Jeffrey Kennedy does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.